European leaders have failed to devise any short-term solutions to address the underlying drivers forcing refugees to flee Africa and the Middle East, pushing some policy makers and  sections of the public to press for closing borders and raising fences and walls. Based on evidence presented in a number of IZA World of Labor Articles, managing editor Olga Nottmeyer argues that not only is it a human responsibility to fight this type of xenophobia, but such nationalist/protectionist policies have also been proven impractical and ineffective from an economic point of view.

sections of the public to press for closing borders and raising fences and walls. Based on evidence presented in a number of IZA World of Labor Articles, managing editor Olga Nottmeyer argues that not only is it a human responsibility to fight this type of xenophobia, but such nationalist/protectionist policies have also been proven impractical and ineffective from an economic point of view.

+++

Whether—and how—to integrate asylum seekers features prominently on the political agenda in so many European countries. And yet, there is no sign of the crisis abating. The situation in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries facing conflict, civil war, and terrorism make it impossible to ignore the challenges associated with the mass migration of people from these areas, and their call to Europe for help. Ignoring the crisis is no solution; neither is xenophobic rhetoric or building more fences and tightening border controls.

There is, however, a sensible approach that would certainly help with integrating refugees in the destination countries‘ labor markets. As Kathryn H. Anderson discusses in detail in her IZA World of Labor (WOL) piece, ‘[labor] migrants earn [considerably] less at entry and it takes many years for them to achieve parity of income’. But ‘policies to increase skills, such as language and local training and work experience, seem to be most effective in promoting assimilation’.

Whether minimum wages are a useful tool in this context as well is empirically unclear. As shown by Madeline Zavodny ‘the scarcity of research on the minimum wage and immigrants combined with the contradictory findings of some research limit the conclusions that policymakers can draw about whether […] immigrants benefit (or lose) from the minimum wage’. However, wage subsidy programs seem to be quite promising. As Anderson writes ‘[they give] the employer an incentive to hire workers who do not have local work experience but are bound by high contracted wages at the start of the job.’ Anderson mentions a three step model in which ‘immigrants are enrolled in language courses based on their education. [Then, they] participate in ALMP [active labor market policies] designed to place them in jobs. [And finally,] employers can receive wage subsidies to hire immigrants for a maximum of one year’.

So while refugees’ economic success will crucially depend on their own efforts and ambitions, in the same way it is for immigrants, it also depends to a great extent on the ability and willingness of the society in the destination country to offer support.

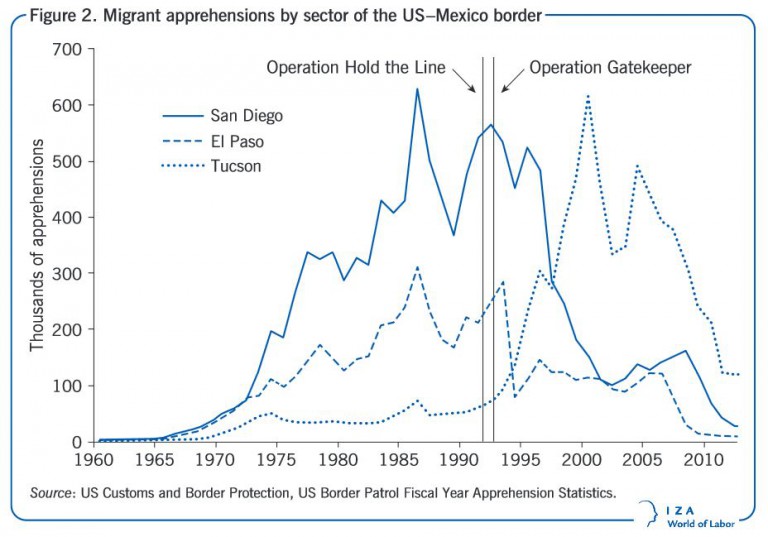

Why does fence building not work? As Pia Orrenius demonstrates impressively in her contribution to IZA World of Labor, ‘intensifying border enforcement leads to […] higher demand for smugglers, riskier crossings and more migrant deaths.’ It will not stop desperate people from coming, but forces them to alter their routes. This happened in the 1990s in the US when border crossings in El Paso and San Diego were impeded and people from Mexico shifted to a different route, via Tucson, to enter the US.

And we see this now when refugees desperately look for legal (or illegal) ways to enter the EU. Increasing the hurdles to gain entry and asylum is not a deterrent in this situation but will merely increase the risks associated with crossing borders, as well as the profits of human traffickers. At the same time, Orrenius writes, ‘[tightening border] enforcement is costly and can divert resources from other law enforcement.’ So in the end stricter border controls and immigration policies will come at high costs, both to the economy and to people’s lives.

So what is the alternative? In his very insightful WOL contribution Jesus Fernandez-Huertas Moraga introduces a combined model of tradable quotas (similar to emission quotas) and matching mechanisms (similar to those used to assign students to their preferred universities) to provide an ’efficient solution which addresses the concerns of the destination countries and protects refugees’ rights.’

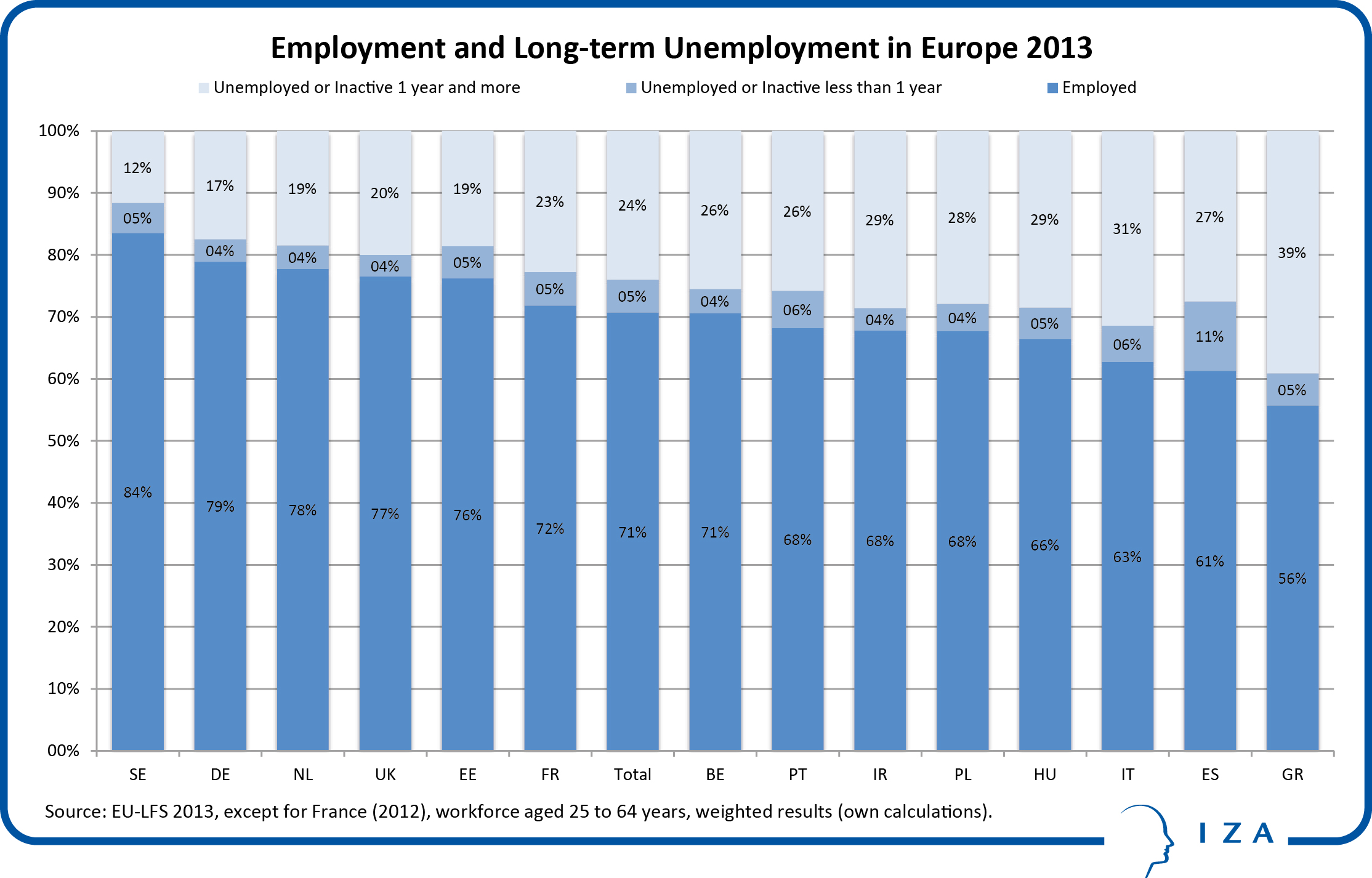

This solution takes into account the needs of the refugees and asylum seekers, while addressing the security concerns of the society in the destination country at the same time. Thus, quotas would need to depend on the capacity of destination countries to absorb refugees, e.g. based on ‘GDP, population, unemployment rate, and the number of refugees resettled and asylum applications received during the previous five years’.

Of course, this does not mean treating refugees like widgets. On the contrary, as Alvin Roth says: ‘Refugees are not widgets to be distributed or warehoused. They are people trying to make choices in their best interest.’

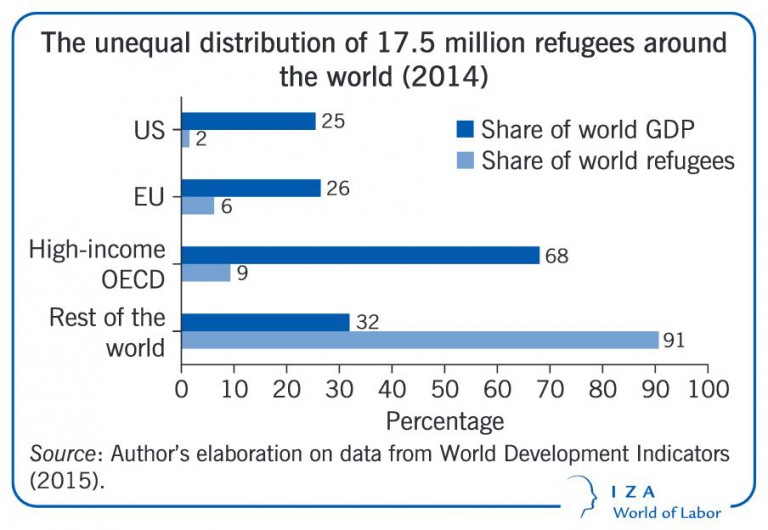

In 2014, the high-income OECD countries gave shelter to less than 10% of the world’s 17.5 million refugees, while the rest of the world (with only 32% of global GDP) took care of 91% of the world’s refugees. This unbalanced distribution simply cannot be the best and only solution. Instead, better coordination is imperative to guarantee ‘greater responsibility sharing and a fairer distribution of refugees across the globe.’

It is thus long overdue for the harmonization of asylum policies to be at the forefront of the European agenda. As explained by Tim Hatton in his impartial analysis of the current European asylum system, international cooperation can be beneficial to both refugees and the population in the destination country if the policies are appropriate. Again, this includes a fair allocation of refugees, skills training tailored to the needs of refugees and of potential employers, sufficient supply of language courses to increase chances to find employment and refugees’ commitment and effort to integrate.

The bottom line is that closing borders and intensifying enforcement does not and cannot solve the problem. Only the combined efforts of all parties —countries of origin, destination countries, the refugees themselves—and international collaboration can pave the way towards a long-term solution and successful economic integration. It is our human responsibility to fight against xenophobia and national barriers, and to create a more inclusive, welcoming society for all.

+++

Olga Nottmeyer is Managing Editor of IZA World of Labor. This article first appeared on the World Bank blog “Jobs and development”.

Aging populations pose a challenge to the fiscal and macroeconomic stability of many societies through increased government spending on pension, healthcare, and social benefits programs for the elderly. This may hurt economic growth and overall quality of life if governments need to divert public spending from education and infrastructure investment to finance programs for the elderly. In addition, the recent economic crisis not only increased the demand for social protection but it also drew attention to population aging issues as many countries faced unsustainable public debts. In many nations, the already-high public spending limits the fiscal possibilities for increased aging-related spending in the long run. Therefore, pertinent and prompt policy solutions are necessary to ensure fiscal and macroeconomic sustainability as well as the health and well-being of citizens of all ages.

Aging populations pose a challenge to the fiscal and macroeconomic stability of many societies through increased government spending on pension, healthcare, and social benefits programs for the elderly. This may hurt economic growth and overall quality of life if governments need to divert public spending from education and infrastructure investment to finance programs for the elderly. In addition, the recent economic crisis not only increased the demand for social protection but it also drew attention to population aging issues as many countries faced unsustainable public debts. In many nations, the already-high public spending limits the fiscal possibilities for increased aging-related spending in the long run. Therefore, pertinent and prompt policy solutions are necessary to ensure fiscal and macroeconomic sustainability as well as the health and well-being of citizens of all ages. Encouraging older workers to remain longer in the labor force is often cited as the most viable solution to fiscal pressures and macroeconomic challenges related to population aging. Phased-in retirement entails a scheme whereby older workers could choose to work fewer hours yet remain longer in the labor force, including after they retire. And gradual retirement can be beneficial to societies, employers, and workers:

Encouraging older workers to remain longer in the labor force is often cited as the most viable solution to fiscal pressures and macroeconomic challenges related to population aging. Phased-in retirement entails a scheme whereby older workers could choose to work fewer hours yet remain longer in the labor force, including after they retire. And gradual retirement can be beneficial to societies, employers, and workers: In cases where individuals are unable to take advantage of phased-in retirement—due to health issues, family obligations, or skills mismatch—governments could promote and reward volunteering, care work, and artistic work among the elderly. Such unpaid activities improve the quality of the social fabric, help the well-being of those engaging in them, contribute to the economy, and reduce healthcare and welfare costs.

In cases where individuals are unable to take advantage of phased-in retirement—due to health issues, family obligations, or skills mismatch—governments could promote and reward volunteering, care work, and artistic work among the elderly. Such unpaid activities improve the quality of the social fabric, help the well-being of those engaging in them, contribute to the economy, and reduce healthcare and welfare costs. “In past decades, Germany has made great strides with the integration of foreigners. Those achievements must be defended prudently and balanced with the country’s demographic challenges. Indiscriminately admitting all refugees from war, including often illiterate and unskilled youths, is bound to undermine these very impressive gains,” writes IZA’s founding director

“In past decades, Germany has made great strides with the integration of foreigners. Those achievements must be defended prudently and balanced with the country’s demographic challenges. Indiscriminately admitting all refugees from war, including often illiterate and unskilled youths, is bound to undermine these very impressive gains,” writes IZA’s founding director  In a recent

In a recent