The current public debate in many developed countries about the future of paid employment is

characterized by strong feelings of uncertainty. Studies emphasizing the potentially deep and severe impact of globalization and automation have nourished fears of significant job destruction in the future. Furthermore, in labor markets that have become increasingly flexible, at least in certain areas of employment, issues such as precarity, unstable employment or low pay have gained attention, in particular in the aftermath of the recent global economic crisis.

At the same time, many of those who are employed perceive work as increasingly stressful and demanding, or psychologically overburdening due to ever growing pressure on performance and work intensification. So what can we expect from the future, based on an assessment of the current and most plausible future developments?

From past and current experience, we know that outdated, simple jobs are threatened by offshoring or outsourcing to foreign locations with lower labor costs, or by automation. Companies and sectors shrink or disappear. However, this process seems to be becoming faster and more radical, especially in the age of information and communication technology where opportunities of digitalization are constantly increasing, sometimes at an unexpected speed.

Thus, many see an expanding threat on a fundamental level to existing jobs and firms in developed economies and a massive imminent disruption of employment trends through the digital revolution. This process of the elimination of jobs on the one hand, with the creation of innovative new ones on the other, has long been known as creative destruction.

Occupations that will be most relevant in the future are those that rely on non-routine cognitive, interactive or manual work performed by human beings, i.e. dealing with complexity, deciding, teaching, but also care and personal interaction. In these areas, human beings are crucial and will likely remain indispensable. And humans shape these jobs based on qualification, experience, motivation and collaboration. Many jobs of the future will rely on this human factor, creating a huge potential of making these jobs ‘richer’ and more intrinsically interesting or rewarding than the jobs in the past, which were often characterized by more routine and repetitive tasks.

While new technologies enable mobile working and technologically assisted interaction, we can see that communication between humans is still vital in many respects, in particular in services tailored to individuals. Given market pressures and competitiveness considerations, there is an increasing tendency to address human creativity and motivation more systematically via organizational and human resource practices. However, on the downside, this can be more invasive to individuals and bring about more external control, not least via contract-based work and stricter monitoring.

Today’s labor markets are heterogeneous. They offer a multitude of employment options along a broad continuum ranging from permanent full-time employment to part-time work, fixed-term contracts, temporary agency work, freelance, zero-hour contracts, on-call work and many others, sometimes including combinations of different forms or multiple jobs.

We see from the current picture that the type of employment relationship varies greatly between occupations. This has direct implications for the working conditions that employees and self-employed or freelance workers face. Working conditions in terms of employment type, contract stability and remuneration depend on skill demand and skill supply with contracts resulting from negotiations between actors always searching for the best deal.

Clearly, firms or contractors tend to externalize economic risks and shift the burden of adaptation to those in a weaker position. Job quality and flexibility is a question of negotiation and bargaining power. Certainly, not all will be self-employed as there is still an advantage to have permanent employees in the firm that make up a stable core work force which can develop specific skills and knowledge that cannot be bought on the spot.

However, even within firms, flexible employment practices flourish, sometimes blurring the boundaries between internal and external project partners. Flexible, performance-oriented practices are also spreading within firms, affecting the work done in formally stable employment relationships. But all in all, there is no general tendency towards more precariousness for all workers, although large and increasing heterogeneity in the labor market is likely to occur. It would be wrong to overestimate problematic and rapid changes in some limited pockets of the labor market by assuming the extension of these challenges throughout the entire labor market.

Public policies can be seen as productive investments in the economic and societal future. The main elements have already been on the agenda, but what is needed is more coherent action. This is particularly true for the area of policies to facilitate and stimulate innovation especially at the interface of research, education and business. Education and training have been top priorities over the last decade or so in many developed economies, and they need to be developed further, leaving no one behind, making vocational training and further training over the life course more systematic and universal, i.e. affordable and accessible, to enable working-age people to participate in the labor market. This will require the mobilizing of social partners, employers, and individuals.

Policies can either encourage or discourage labor market participation for all. With demographic ageing, better and more substantial labor market participation becomes ever more important, in particular with respect to women, older workers – requiring a broader definition of the working age – and the unemployed or inactive people. This requires supportive services and investment in skills on the one hand, but also a quite flexible labor market on the other. Labor markets of the future should be open to facilitate entry and to encourage mobility between jobs, firms and activities, as well as longer working lives.

Given that the future of work will be characterized by diverse job options, a certain amount of heterogeneity in terms of working conditions is inevitable and should not be suppressed by heavy regulation. This would actually encourage exclusion of some groups or the circumvention of regulation and other negative side effects. In particular if skills in the workforce are diverse, entry positions and low pay are necessary. This calls for a rather open and flexible regulatory framework setting fairly wide boundaries, but also some outer limits to acceptable forms of employment.

The reconciliation between employer and individual objectives is probably one of the core issues regarding the future of work. In fact, the future of work will mostly be shaped by corporate practices aiming at productivity, innovation and speed for the sake of competitiveness. But at the same time, demands on workers cannot be increased indefinitely. Physical and mental health issues have gained importance as has the search for solutions to ensure a proper work-life balance under new economic circumstances.

Hence, human resources policies and organizational innovations that help reconcile productivity and attractiveness of the workplace will contribute substantially to the success of firms when competition on markets, including the market for talent, is strong. To attract qualified people, work needs to be attractive regarding the fairness of effort and reward, as well as the willingness of employers to negotiate flexibly with potential and incumbent workers on their working conditions, including working time patterns, mobile working, individualized career paths, etc. This provides considerable scope for flexible, negotiated solutions at the company, department or individual level. However, as of yet, this tends to be a privileged situation for those whose skills are scarce. Finally, while allowing for differences and diversity, firms also need to observe overall fairness in the treatment of all of their workers.

The future world of work will certainly be demanding, maybe more than in the past, for individuals, but it will also offer many opportunities. All jobs are potentially subject to change and can become obsolete. Hence, there is no absolute security of employment, but rather a permanent situation of trial, probation and assessment. Future jobs can be long-term and permanent, of course, but there is no guarantee for that.

Furthermore, current and future work will be fluid, unlimited in many cases, in its interaction or integration with the rest of life, with a stronger emphasis on subjective involvement, requiring self-organization, professionalism, articulation and communication. This is particularly relevant for knowledge- and project-based work. To be able to cope with these demands, education and training matter, not only formally, but also informally, such as those skills acquired during practical experience in non-routine work like this. These jobs are potentially rewarding as they allow for a personal shaping of tasks according to talent, taste or style. However, while full engagement and identification are seen as desirable and competitive assets, this raises psychological issues in terms of stress, exhaustion and mental health. The demands of the new world of work require a more in-depth discussion of these issues.

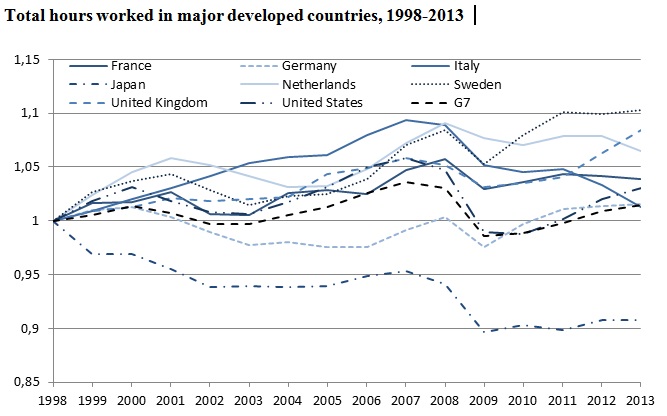

The changes we have discussed are more incremental than disruptive. This means that we can expect that actors have some time and capacity to adapt and negotiate solutions. Clearly, we do not really face a situation of massive joblessness in developed market economies beyond the cyclical and partially structural unemployment observed currently. But there can be no doubt that the world of work will be different from what we know today.

Still, this is no reason to be afraid. As history has shown, human creativity and inventiveness are strong and will always find ways to cope with new situations, including creating new job profiles in the future. We have been living with technological progress, globalization and structural change for decades and will continue to do so in the future. There is no big master plan, but there is a great deal of micro-level action, with public policies setting a more or less favorable framework for market actors.

This article also appeared in the World Commerce Review, December 2014.