People have different propensities to tell the truth, particularly when there is an incentive to lie. According to an experiment conducted with soldiers and civilians in Israel, researchers found that it’s not the differences in religious, economic or social background that determines who is more willing to lie or tell the truth. Instead, the analysis by Yossi Tobol (Jerusalem College of Technology) and Bradley J. Ruffle (Wilfrid Laurier University) revealed a striking correlation between honesty and cognitive ability.

People have different propensities to tell the truth, particularly when there is an incentive to lie. According to an experiment conducted with soldiers and civilians in Israel, researchers found that it’s not the differences in religious, economic or social background that determines who is more willing to lie or tell the truth. Instead, the analysis by Yossi Tobol (Jerusalem College of Technology) and Bradley J. Ruffle (Wilfrid Laurier University) revealed a striking correlation between honesty and cognitive ability.

The truth-telling experiment was conducted with a group of 427 Israeli soldiers and repeated with 156 random passersby in an Israeli shopping mall. After a survey about individual characteristics, the participants were asked to roll a six-sided die in private and then state the rolled number. Higher reported numbers were rewarded with spare time for the soldiers and small monetary incentives for the civilians.

The truth-telling experiment was conducted with a group of 427 Israeli soldiers and repeated with 156 random passersby in an Israeli shopping mall. After a survey about individual characteristics, the participants were asked to roll a six-sided die in private and then state the rolled number. Higher reported numbers were rewarded with spare time for the soldiers and small monetary incentives for the civilians.

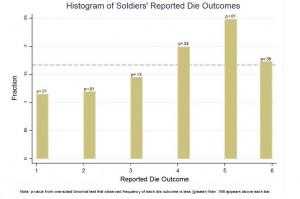

Common sense about rolling a fair die tells us that each side should show up with about equal frequency. Here is what the soldiers’ results look like (the civilian results are similar):

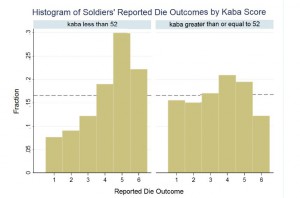

Higher numbers were disproportionately reported by both the soldiers and civilians. Interestingly, the authors found that one specific characteristic was related to differences in reporting. Soldiers who scored higher on cognitive ability in their military entrance test (kaba) were less likely to over-report by lying about their die roll.

This result is somewhat surprising in that rewards for lying in this experiment are clear and straight-forward (rewards in spare time/money). Still, however, there are costs associated with lying, for example, through later detection and/or an eroded self-image of honesty. The authors suggest that higher cognitive-ability subjects are able to think through these costs and, as a result, resist the temptation to inflate their die reports.

This result is somewhat surprising in that rewards for lying in this experiment are clear and straight-forward (rewards in spare time/money). Still, however, there are costs associated with lying, for example, through later detection and/or an eroded self-image of honesty. The authors suggest that higher cognitive-ability subjects are able to think through these costs and, as a result, resist the temptation to inflate their die reports.

- Read coverage in the Washington Post’s Wonkblog (April 14, 2016):

The importance of such internal costs of lying via an eroded self-image have also been shown in a phone call experiment conducted in Germany by Johannes Abeler (University of Oxford and IZA), Anke Becker (University of Bonn) and Armin Falk (briq and IZA), published as IZA DP No. 6919. These authors find almost no pattern of lying in their experiment despite the fact that detection was virtually impossible and thus the reputation costs were almost negligible.