With the expansion of residential high-speed internet and new telecommunication tools, teleworking is no longer just for self-employed workers. According to the American Time Use Survey, the number of salary workers in the U.S. who regularly work from home more than doubled between 2005 and 2015. The reduced wage penalty for teleworkers, increased work-life balance conflicts, and rising female labor force participation add to this trend.

Homeworking comes with pro and cons. While some describe as an ideal that combines family life and work, others depict it as chaotic and stressful – just imagine your cat sitting on the laptop, your baby crying on the ground, and your dog biting the shoes. According to a recent IZA discussion paper by Younghwan Song and Jia Gao, the extra stress associated with working from home should not be underestimated.

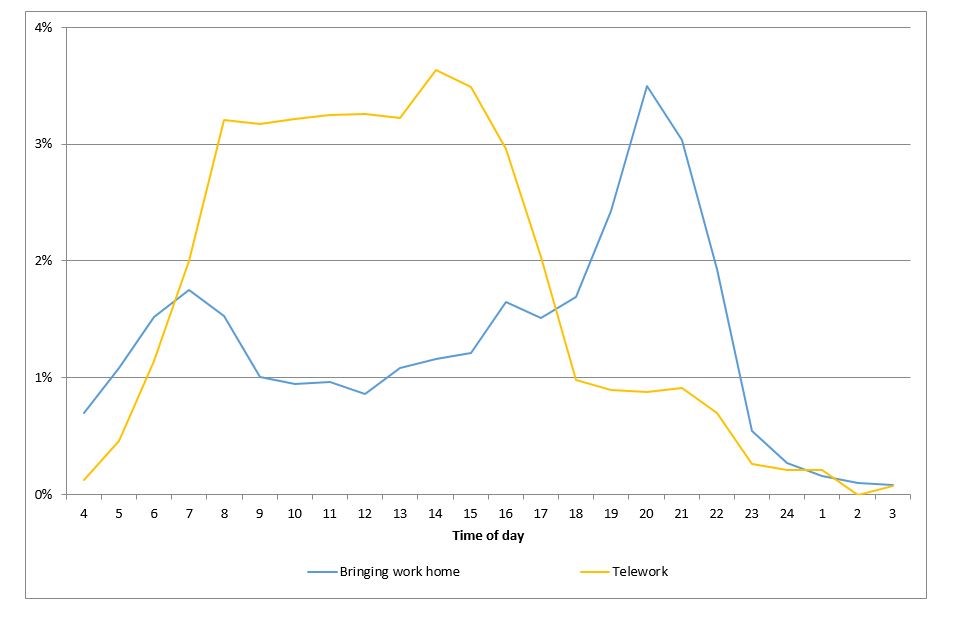

The authors emphasize the importance of distinguishing between telework (working at home without commuting to the office) and bringing unfinished work home from the office. As the figure below shows, telework mainly takes place during regular office hours on weekdays while office workers’ extra work at home peaks in the early mornings and late evenings.

To evaluate the impact of these modes of teleworking on salary employees’ instantaneous subjective well-being, the authors analyzed the emotions felt by a sample of nearly 4,000 salary employees when they work from home. Since the negative effect of telecommuting may be overestimated if people who are more likely to work at home are also those who are more prone to feel tiredness and stress because of taking care of children or elderly, the study compares changes in work arrangements and well-being within the same person.

Decrease in subjective well-being

In general, the authors find that working at home is associated with a lower level of “net affect” (positive minus negative emotions) and a higher probability of having unpleasant feelings compared to office work. Although teleworkers feel less tired, probably because of the time and energy saved on commuting, they experience more stress, which may be due to increased conflicting demands of work and home, and the blending of personal and professional life.

Bringing work home on weekdays also results in a lower subjective well-being as it is associated with more stress and less happiness. The authors rule out longer working hours per se as an explanation but instead point at conflicts in the family about time arrangement between working hours, household chores, and leisure.

More support for homeworkers

Although the new study cannot resolve the whole debate on home-based work, it highlights the importance to differentiate formal telework from informal overtime work at home in evaluating homeworking. The results also underscore the need for employers to reconsider the potential well-being impacts of homeworking and rethink the benefits of telework for their employees.

To enhance life quality, the authors conclude that policymakers and employers should provide more support to homeworkers such as childcare, care for aging parents, suitable workspaces, and a social network that can sustain homeworking practices. All this would help homeworkers cope with the loneliness, stress, and work-family conflicts, and help them develop boundaries in time and space between the worlds of home and work while maintaining high levels of self-motivation.