The COVID-19 pandemic has had vast tragic human consequences. The human suffering brought about by the pandemic and its economic consequences are depressing in the short run. A new IZA discussion paper by Louis-Philippe Béland, Abel Brodeur, and Taylor Wright studies the economic impacts of COVID-19 on workers in the United States.

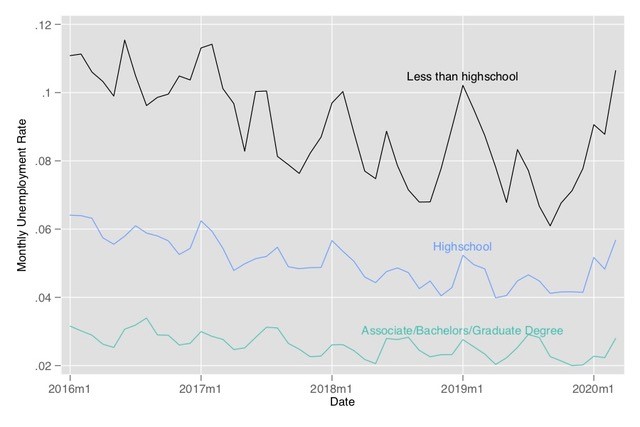

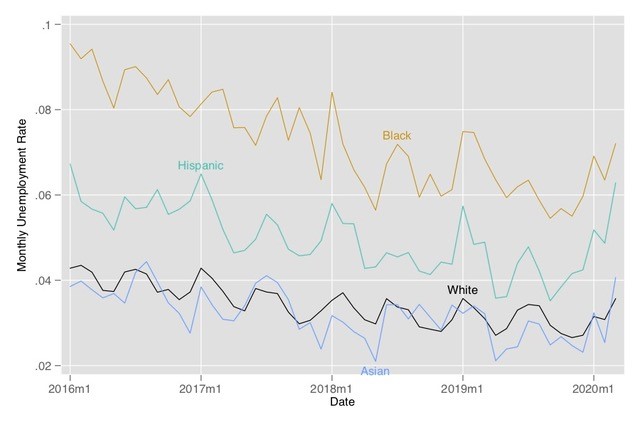

Using monthly U.S. employment data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a nationally representative survey, the authors find COVID-19 had negative impacts on short-term labor market outcomes (unemployment, wages, hours worked, and labor force participation) in the US especially for men, younger workers, immigrants, Hispanics and less-educated workers (see Figures below for a look at unemployment).

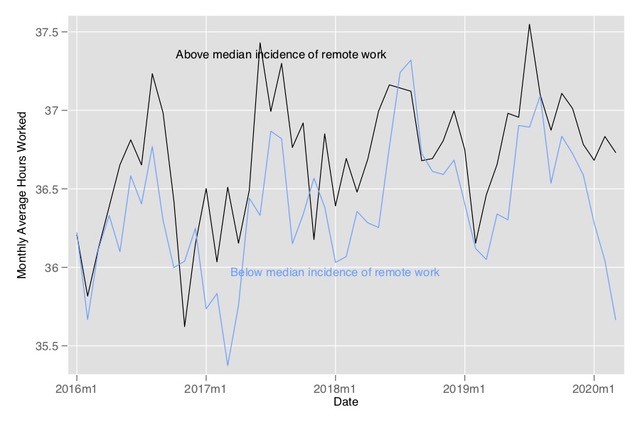

In order to gain further insight into which workers are more or less likely to be impacted, the researchers look at workers in occupations that are more exposed to disease and infection; working more closely in proximity to others; and are more likely to work remotely. Occupations are classified based on whether they are above or below the median index value for each of these indexes.

The Figure below illustrates the three indexes. Each circle in the figure represents an occupation. The size of each circle represents the number of CPS respondents employed in that occupation: the larger the circle, the greater the number of people employed in that occupation. The x-axis plots each occupation’s physical proximity to coworkers, measured by O*NET‘s index. The further to the right, the closer in proximity employees in that occupation work with their coworkers. The y-axis plots each occupation’s exposure to infection and disease, also measured by O*NET’s index. The further up, the more frequently employees in that occupation are exposes to infection and disease. The color of the circles corresponds to the quartile of each occupation in the remote work index constructed by the authors. Occupations in the first quartile are not commonly done from home while those in the fourth quartile are more commonly done from home.

The results show that individuals in occupations working in proximity to others are more affected in terms of negative labor market outcomes while occupations able to work remotely are less affected (see Figure below for a look at hours worked). The authors also find that occupations classified as more exposed to disease are less affected, possibly due to the large number of essential workers in these occupations.

These results are important given the current tradeoff faced by state governors between employment and disease prevention. As policy makers look to help displaced and affected workers, these findings highlight some of those most in need of assistance. Looking forward, these insights can aid policy makers in prioritizing which occupations and workers should be allowed to resume usual activities.