By Miles Corak

University of Ottawa and IZA

The Great Recession has disrupted the lives of families and their children in an unprecedented way.

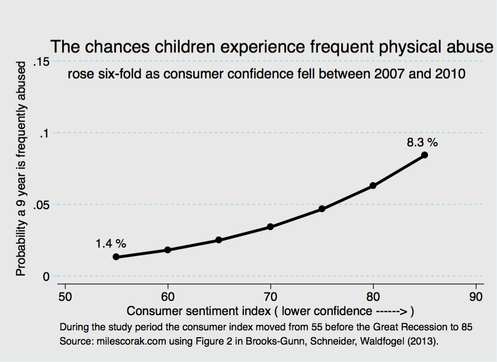

It has changed everyday life in some ways that can be measured by money, but in others that cannot, and at the extreme it has even led to a six-fold increase in the risk children will be physically abused.

Lost jobs, falling incomes, and foreclosures will likely compromise the capacity of children to become all that they can be, with the effects of the recession echoing not just across years, but also across generations.

Recessions do not normally figure into the way economists think about the factors determining the adult prospects of children. Unemployment spells are usually short, temporary events. In gauging the capacities of families to invest in and promote the capabilities of their children, it is important to look past the changes in incomes that result, and focus on the long-term, more permanent, resources available to parents.

Family income measured in any single year is, for example, not a good predictor of the adult incomes of children, but an average over, say, 10 years offers a better picture of family wealth, and is much more strongly associated with adult outcomes.

Economic theory teaches us, that people base their spending decisions, along a whole host of dimensions, on their expected long-run earnings prospects.

Certainly buying a home is made on this basis, young couples entering into debt because they expect their earnings to grow over the decades with more and more job experience. Investing in your children is no different: which schools and colleges they attend, what vacations to go on, what other extra-curricular expenditures and care arrangements to make, are all decisions that need not be rethought if income decreases, or for that matter increases, temporarily for a short period of time. Borrowing, drawing down savings, or government support can make up the difference, and maintain a customary life style.

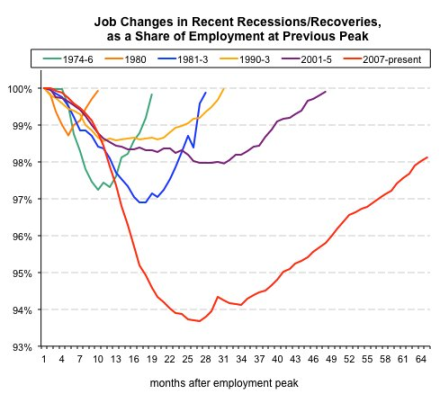

But the Great Recession, unleashed with full force in the autumn of 2008 and from which the American economy has yet to fully recover, has shattered both reality and expectation.

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/03/comparing-jobs-in-recessions-and-recoveries-2/

Its severity and duration calls us to rethink this rather sanguine point of view.

Research has shown that losing a job with no prospects of getting recalled lowers the incomes of long-tenured workers by as much as 25%: the new jobs these workers eventually find rarely pay as much as the old jobs they lost.

Just as importantly, this has a long-term impact on children.

The loss in income matters, but so do the other accompanying changes that will also influence the way they lead their lives. The Great Recession has certainly caused major, long-term income losses for many families, but this matters all the more because it was associated with the bursting of a housing bubble that unleashed an unprecedented number of foreclosures.

This means some children are not only living in poorer families, but that they also face the disruptions associated with changing schools, neighbourhoods, and even cities. Frequent moves and a repeated loss of friends and networks lowers high school graduation rates, and the adult incomes kids will ultimately earn.

The Great Recession didn’t just deplete bank accounts and disseminate home equity; it also ushered in a major crisis of confidence. Family life, even among those who did not experience job loss, is much more stressful, making parenting a bigger challenge.

Children benefit most from a so-called “authoritative” parenting style, a loving and warm relationship that also offers clear expectations of behaviour and accomplishment. But financial strain, whether subjective or not, taxes the energies of parents, and raises the likelihood of “authoritarian” behaviour, which involves strict adherence to rules, and unfair punishment to enforce them.

A telling, if extreme, example is a recent finding that during the Great Recession children have been more likely to fall victim to physical abuse.

A soon to be published research paper by Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, William Schneider, and Jane Waldfogel, researchers at Columbia University and the London School of Economics, shows that the drop in consumer confidence beginning in 2007 is associated with a six-fold increase in the chances that mothers will hit their children frequently (on about at least a monthly basis).

Before the recession, less than two per cent of the nine year-olds they studied in America’s major cities were at risk of being abused in this way, but when the drop in consumer confidence reached is nadir, close to 8% were.

A recession is usually a short, temporary event, something that can even be planned for, or at least weathered by a combination of personal savings, insurance, and income support. But the Great Recession was deeper, has lasted longer, and has unleashed a whole host of long-term changes. These will most likely scar some children by compromising the quality of their home life, making them the silent victims of these turbulent times.

This is a reblog of the original article published at milescorak.com.