By Giuseppe Lucio Gaeta, Giuseppe Lubrano Lavadera, and Francesco Pastore

Gaining a Ph.D. possibly determines positive outcomes from both an individual and a societal perspective. For candidates, doctoral education is an investment aimed at acquiring skills and competences to be used in future career. For the society as a whole those who achieve a Ph.D. are likely promoters of innovation. In order to achieve these outcomes, Ph.D. holders must be able to get job positions that allow them to fully exploit their educational background. How frequently does this occur?

Gaining a Ph.D. possibly determines positive outcomes from both an individual and a societal perspective. For candidates, doctoral education is an investment aimed at acquiring skills and competences to be used in future career. For the society as a whole those who achieve a Ph.D. are likely promoters of innovation. In order to achieve these outcomes, Ph.D. holders must be able to get job positions that allow them to fully exploit their educational background. How frequently does this occur?

A crucial question in Europe and in Italy

This question is particularly important in Europe nowadays. Starting from the Bologna Process, doctoral studies are interpreted as the third cycle of education and therefore public as well as private entities, alongside the academia, are considered as possible destinations for Ph.D. holders. This makes it very important to investigate whether the job-education matching is frequent among Ph.D. holders.

Italy is an appropriate context to investigate this issue for two main reasons. First, a remarkable growth of doctoral education has been reported in this country over recent years. Data reveals that at the beginning of the 2000s the annual number of new Ph.D. holders was approximately 3,000 while few years later, in 2006 it was higher than 10,000. Nevertheless, in 2011, the Italian graduation rate at a doctoral level was still lower than the OECD average.

Second, in Italy the size of personnel devoted to research and development (R&D) is lower than the EU28 average. Personnel working in Italian universities has been declining from 2008 (-17%, data provided by the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research), while over recent years (2007-2013) an opposite increasing trend (+33%) is reported for the R&D personnel working in private firms.

Unemployment and overeducation

In 2009, ISTAT carried out a survey of Ph.D. holders who completed their studies three and five years earlier, in 2006 and in 2004, respectively. The data reveals that unemployment among Ph.D. holders is lower than what is reported for university graduates. A share as high as 92.5% of doctors who completed their studies in 2006 was working at the time of the survey and the figure is even higher in the case of those who graduated in 2004 (93.7%).

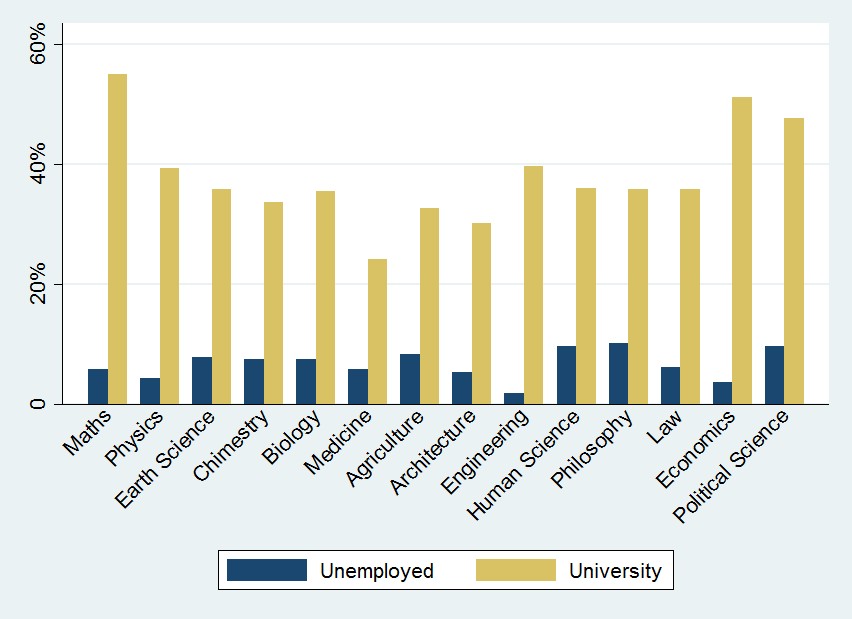

Figure 1 confirms this, while also showing that there is high heterogeneity of unemployment rates across fields of study, since Human Sciences and some of the Social Sciences perform worse than other fields. The share of Ph.D. holders working in the academia after the completion of their studies is approximately 36% with a remarkable variability among fields of study; it is higher in Mathematics and Physics and lower in Law and Life Sciences (see figure below).

Source: IZA DP No. 10051 based on ISTAT data.

What about the job to education matching among those who work outside of the academia? Approximately 31.28% of them report that their Ph.D. title was not useful to get the job they were carrying out when interviewed. Nevertheless this figure does not tell us anything about skills utilization.

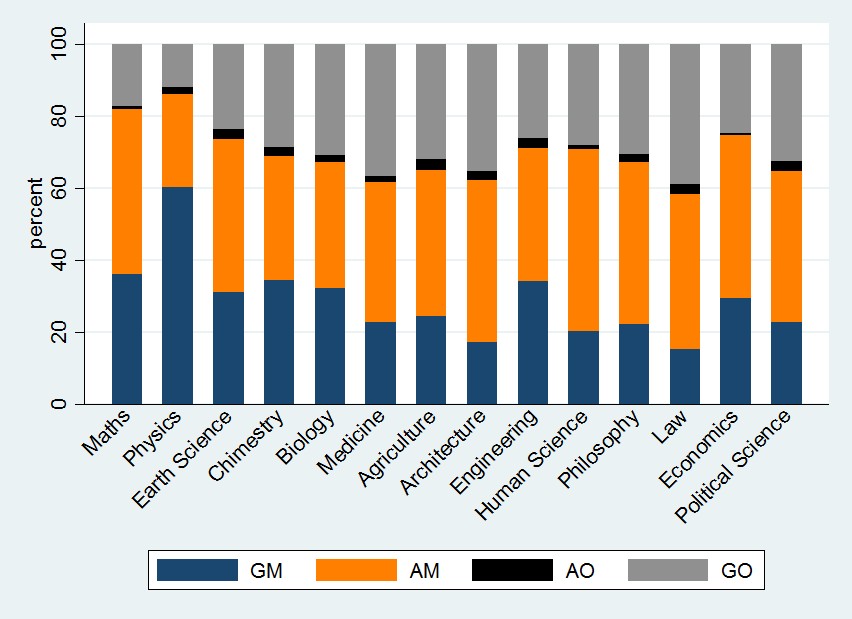

In order to provide a more in depth analysis, we used the ISTAT self-reported data to observe for each of the respondents which of the following alternative situation applies: 1) genuine overeducation (GO) defined as holding a job for which the Ph.D. title and the skills acquired during doctoral studies are useless; 2) apparent overeducation (AO) that arises when the Ph.D. title was not useful to get the current job while doctoral competences are valuable in carrying it out; 3) apparent matching (AM), that arises when doctoral education was useful to get the current job but Ph.D. skills are not; 4) genuine matching (GM) defined as holding a job for which both the Ph.D. title and skills acquired during doctoral studies are useful.

Figure 2 shows the incidence of these conditions among the surveyed doctorate holders who work in the extra-academic by field of doctoral studies. Data suggests that GO is particularly frequent among those who studied Philosophy, Law, Political Sciences and Human Sciences. Particularly worrying is that the sum of GO and AM results to be higher than 50% in most of the fields of study, which suggests that the application of skills acquired during Ph.D. studies is critical.

Source: IZA DP No. 10051 based on ISTAT data.

The detrimental effect of overeducation on wages

This mismatch presumably affects in a negative way the Ph.D. holders’ capacity to generate positive outcomes for the society but also individual private returns to education might be harmed by it.

To check whether the latter claim is true, our recent IZA Discussion Paper relies on the cross-sectional data presented so far. We account for the possible endogeneity of GO by proposing an instrumental variable analysis in which the instrument is represented by the incidence of GO among those who share the same profile of respondents in terms of field of study, area of residence and year of graduation.

According to the empirical investigation, GO leads to a wage penalty of approximately -9%. This effect is remarkably higher (approximately -25%) when the GO status of respondents is defined in a slightly different way, i.e. when we consider as genuinely overeducated those who hold a job for which the Ph.D. title is useless and who are totally dissatisfied with the current use of the skills acquired during their doctoral studies.

Conclusion

While most of research focuses on the career outcomes of university graduates, our essay suggests that there is also need of investigating those of doctors. Since Ph.D. holders are considered to be crucial actors in knowledge economies, incentives should be designed in order to ease the application of doctoral knowledge in non-academic jobs and support the dialogue between the academic and non-academic world in defining some specific topics for Ph.D. training.

Keeping in mind these aims, it is very important to carry out a careful assessment of projects such as the recently released Italian Ph.D.ITalents, which is specifically aimed at easing matching between supply and demand of doctors.

Image Source: Pixabay

+++

On a related note, see also Hilmar Schneider’s recent op-ed (in German) published in Wirtschaftswoche: