With populations aging in across most developed countries, governments are under pressure to reform pension schemes to guarantee their fiscal sustainability. Raising the statutory retirement age – the age at which individuals are entitled to ‘full’ retirement benefits – is one of the most common policy responses already applied in many settings.

With populations aging in across most developed countries, governments are under pressure to reform pension schemes to guarantee their fiscal sustainability. Raising the statutory retirement age – the age at which individuals are entitled to ‘full’ retirement benefits – is one of the most common policy responses already applied in many settings.

However, concerns arise about consequences for workers in demanding occupations. While in many jobs people are able to work much longer, more demanding occupations require workers to retire before reaching any statutory retirement age, thereby entering less favorable early retirement, unemployment, or disability schemes.

In the Dutch policy debate, it was argued that low-skilled construction workers cannot work longer since their job requires a level of physical health they are unable to longer maintain at an older age due to the strains of many years of heavy physical work. Soon several other occupational groups argued for exceptions, too.

Despite these concerns, and out of practical implementation problems, the Dutch government decided to raise the statutory retirement age without any exceptions. While the Dutch discussion is far from over, similar debates are ongoing in Belgium, the UK and potentially any other country that raises the statutory retirement age.

Which occupation is considered more demanding than others?

At the core of these debates lies the question of what qualifies as a demanding occupation. When policy makers have to decide where to draw the line, public opinion is a crucial factor. A recent IZA paper by Niels Vermeer, Mauro Mastrogiacomo and Arthur van Soest analyzes the opinion of the Dutch population on early retirement arrangements of demanding occupations.

The study uses survey data on a sample of over 1,800 Dutch adults (the CentERpanel), which was collected in 2012, in the midst of the policy debate on demanding occupations. The authors seek to analyze which characteristics cause an occupation to be perceived as demanding in the public eye. Secondly, they want to examine how the perceived burden of an occupation affects the reasonable retirement age and the willingness to contribute to an occupation-specific early retirement scheme.

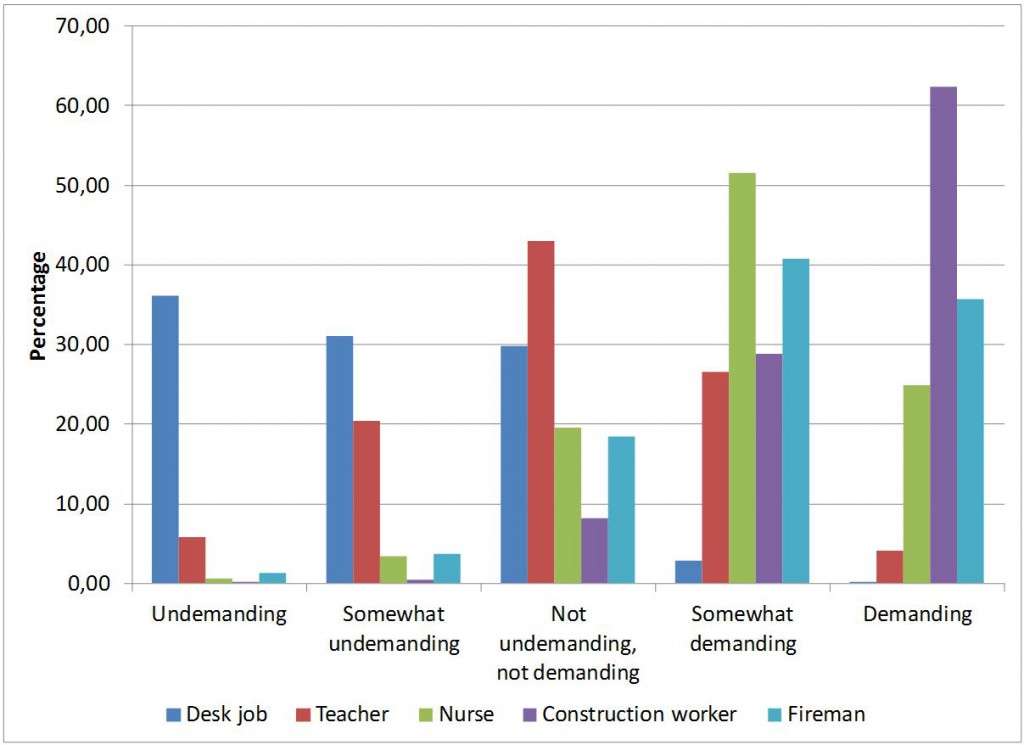

The results paint a clear picture of what is perceived as a demanding occupation: Respondents attach much weight to physical effort while mental effort or job stress is not regarded as demanding. As illustrated in figure 1, they see “construction worker” as a burdensome occupation, but not “teacher” or “desk job”, while “nurse” and “firefighter” range in between.

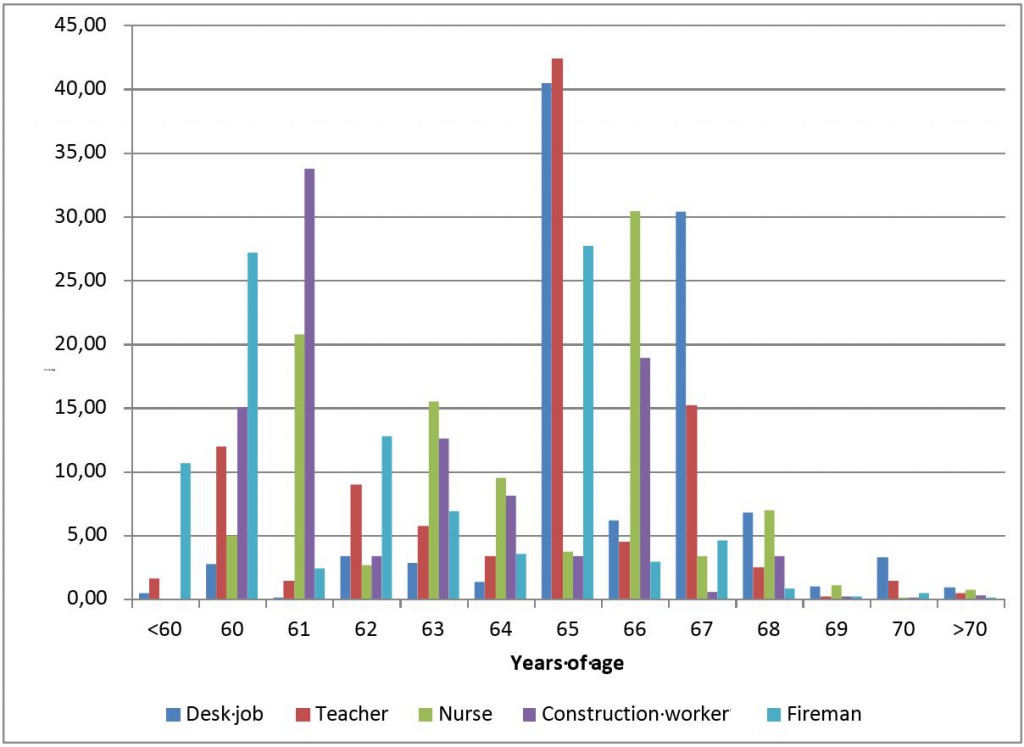

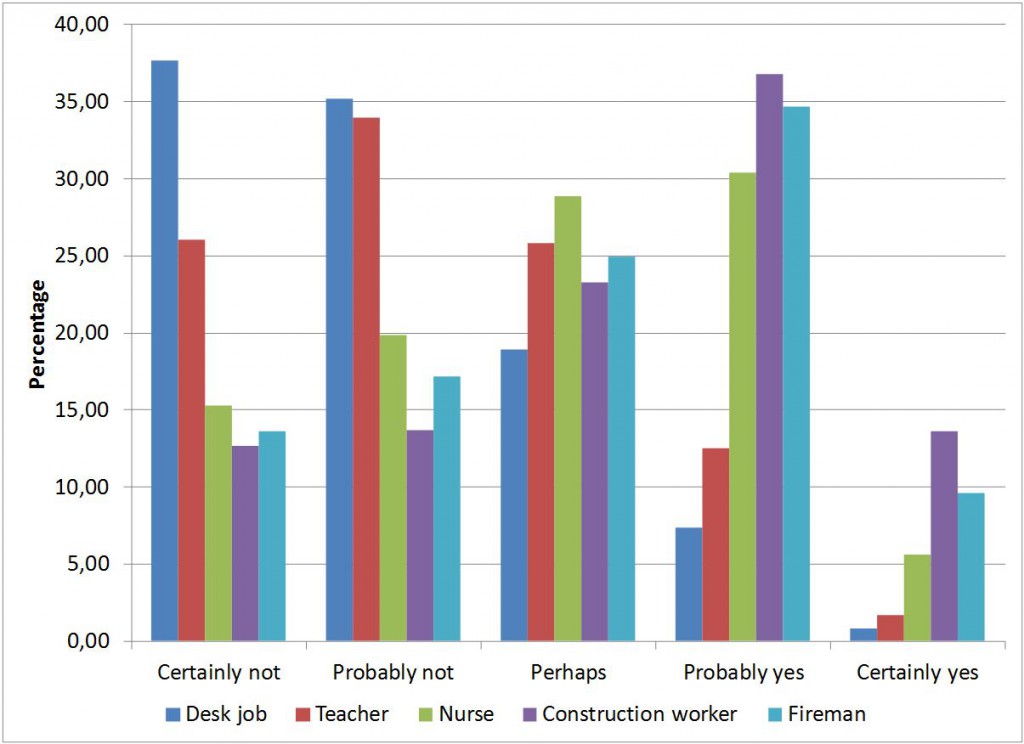

As figure 2 shows, respondents think that construction workers should be able to retire earlier than people with other occupations, while workers with a desk job should work the longest. For the willingness to contribute to an early retirement scheme, the results are similar (figure 3): People show a much larger willingness to contribute to an early pension for construction workers than for firefighters or nurses. Respondents were even less inclined to pay for an early retirement scheme for teachers and employees with a desk job.

These figures are confirmed by a more thorough statistical analysis. Respondents who perceive an occupation as more demanding think that individuals with this occupation should be able to retire earlier. Respondents agree that a worker in a demanding occupation should be allowed to retire about two years earlier. Moreover, respondents indicate a willingness to pay higher taxes for a more generous early retirement scheme, irrespective of whether they work in a demanding occupation themselves.

Exceptions provide disincentives for employers and employees

What do these findings imply for public policy? The Dutch government concluded that differentiating the age of state pension eligibility was unfeasible in practice, reducing incentives for employers to invest in new technology and preventing workers in demanding occupations to change to a less demanding job at a later age.

Vermeer, Mastrogiacomo and van Soest discuss a policy proposal basing the eligibility age on the number of years worked over the lifetime, with adjustments for unemployment, disability, or parental leave. Such a system was recently introduced in Germany, where the statutory retirement age is (gradually) raised to 67, but workers with 45 years of pension insurance contributions can retire at age 63 with full pension benefits.

According to the authors, this policy is easier to implement and discourages strategic behavior. At the same time, individuals with physically demanding occupations would benefit since they often have low education levels and start working at an early age.