We take cues about how to behave from other people, especially in times of great uncertainty like the current COVID-19 pandemic. Home-bound, many currently turn to the media to learn about the actions of fellow citizens and political leaders.

Imagine you are watching the evening news and you see coverage of people defying social distancing guidelines, partying on the beach or congregating in restaurants. Would you give up on flattening the curve or increase your efforts to make up for failings of others? What if, instead, you saw reporting of thousands of people volunteering as health workers in their communities? Would you be inspired and join in or sit back knowing that others will fill in the void?

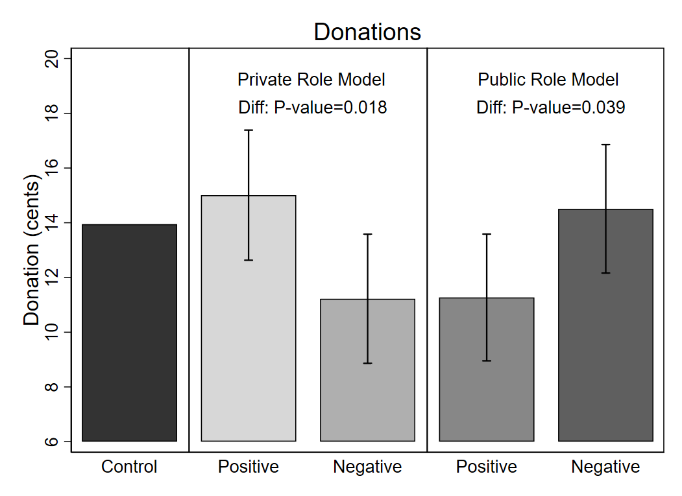

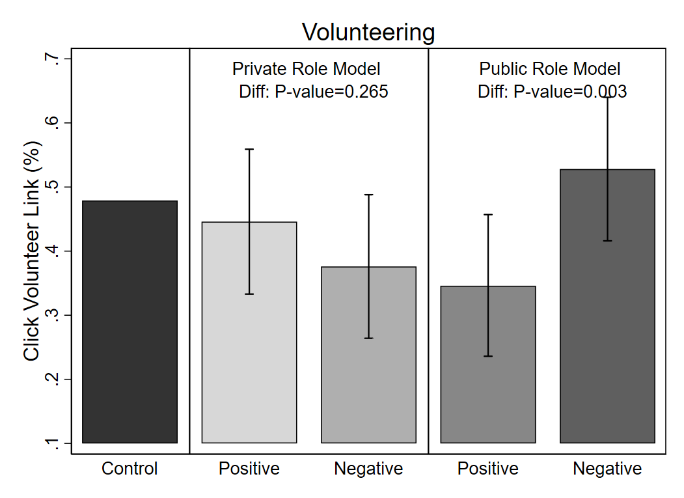

A new IZA discussion paper by Martin Abel and Willa Brown provides some answers to these questions, based on an experiment with people recruited online in the United States. The researchers randomly assigned participants to watch a video showing either private citizens or politicians behaving in ways that have either a negative or a positive effect on preventing the spread of the coronavirus. They measure effects on two forms of prosocial behavior: how much of their participation bonus they donate to the CDC Emergency Fund, and whether they spend time learning about local volunteering opportunities related to COVID-19.

Inspired by citizens, compensating for politicians

Participants who watch positive citizen role models donate 34% more of their bonus and express more interest in volunteering than those watching people disobey social distancing guidelines.

Results look very different for public role models. Participants who watch elected officials acting prosocially (leading the public health response) donate 29% less and are 53% less likely to take steps to learn about volunteering opportunities compared to people who watch politicians mismanaging the crisis, while engaging in insider trading.

In sum, the findings suggest that the actions of government officials are seen as substitutes, those of fellow citizens as complements to the participants’ own actions.

Trust norms vs. feeling responsible

These results can be reconciled by the Norm Activation Model (NAM), which posits that prosocial behavior depends on both the adoption of prosocial norms and a sense of responsibility among individuals for taking actions that satisfy those norms.

Trust is one of the key norms among groups that succeeded in acting prosocially and avoiding prisoner’s dilemmas. Studies find that the majority of people are “strategic cooperators”: they are willing to contribute to a public good if they believe that others will do the same. The paper by Abel and Brown finds that trust is influenced by the actions of private role models: people who watched positive examples are 21% more likely to agree with the statement “Most people can be trusted” than those who watched the negative examples of private role models.

By contrast, public role models do not affect trust norms. They do, however, influence whether people feel responsible to contribute to a collective action problem. Watching the video of failing political leaders leads to a 70% increase in the share of participants who report that personal responsibility to take action was an important factor in their decision how much to donate. This increase in responsibility and prosocial behavior when exposed to negative public role models was particularly strong among women.

Overall, positive private role models are effective because they increase norms of trust. Negative public role models increase prosocial behavior because they increase people’s responsibility to “step up” and take action.