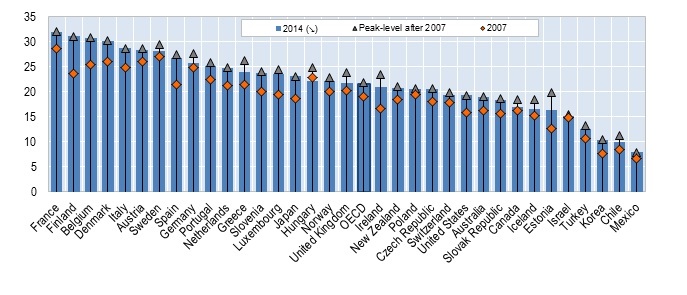

In 2014, the OECD average in public social spending was about 22% of GDP, with upward trends being observed in almost every country. The question about the role and extent of state interventions is at the core of the economics profession, and most economists have been traditionally skeptic about the steady growth in the magnitude of public spending.

Source: OECD Social Expenditure Database.

While political scientists interpret this rising importance of the state as the outcome of the collective desires of voters, it remains unclear in how much the public debate might be based on false beliefs and expectations about the current size of government spending. If citizens are imperfectly informed about the actual extent of public expenditures, the size of government may not be well aligned with their preferences.

With these questions in mind, researchers Philipp Lergetporer, Guido Schwerdt, Katharina Werner, and Ludger Woessmann analyze in their new IZA Discussion Paper how information about actual levels of public spending affects German citizens’ support for increased public spending.

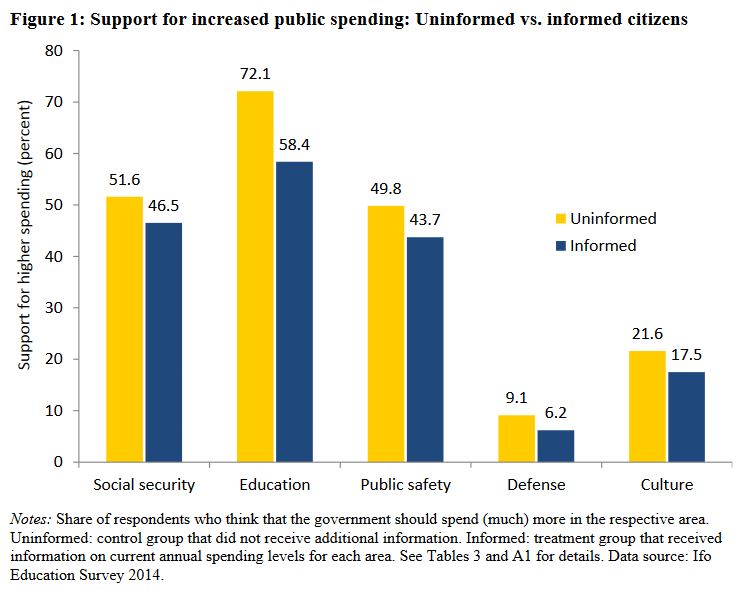

The authors devised a series of experiments in a survey with over 4,000 respondents who were randomly classified into a control and a treatment group and asked about their preferences for increased spending in Germany. Prior to the survey, the treatment group was provided with information on current levels of public spending: €227 billion on social security, €95 billion on education, €38 billion on public safety, €27 billion on defense, and €10 billion on culture. The control group, on the other hand, was not provided this information before the questions were asked.

The results summarized in Figure 1 highlight a strong correlation between the provided (or withheld) spending information and the level of support for increased spending levels. Across all domains, the informed individuals showed less support for more spending compared to individuals who did not receive the information, with the strongest differences found for education.

The results summarized in Figure 1 highlight a strong correlation between the provided (or withheld) spending information and the level of support for increased spending levels. Across all domains, the informed individuals showed less support for more spending compared to individuals who did not receive the information, with the strongest differences found for education.

The observed differences depending on access to information indicate that a sizable share of respondents hold incorrect beliefs about current spending levels. To delve deeper, in a follow-up experiment the authors confirm that the results are primarily driven by those who underestimated actual spending levels before receiving the true information, while well-informed individuals did not react to the additional information.

Taken together, the results imply that high levels of public support for growing public spending levels are actually based on a lack of information, and providing accurate spending information may be expected to lower public support for increased government expenditure.