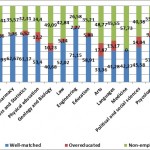

Nobel laureate Chris Pissarides suggests that in times of recession it’s good for young people to acquire more education. Nonetheless, this remedy may be risky if later on young people find a job for which they are overeducated or overskilled. A new IZA Discussion Paper by Floro Ernesto Caroleo and Francesco Pastore provides the first available evidence based on AlmaLaurea graduates in Italy that for a large number of them the educational mismatch is not a transitory phenomenon: as shown in the figure (click to enlarge), five years after graduation 11.4% and 8% of graduates still experience overeducation and overskilling, respectively. Most arts degrees and social sciences, but also Geology, Biology and Psychology are associated with both types of mismatch. Moreover, the non-employment share is dramatically high for most degrees, with an average of 40%. It ranges between a minimum of 27% in the case of Engineering and a maximum of about 50% in the case of Geology and Biology.

Why are so many graduates non-employed or overeducated/overskilled? The main factor is certainly the low demand for skills typical of the Italian economy, still largely based on traditional manufacturing and services. Nonetheless, keeping constant the level of demand, is there any unexploited component of it which could be reactivated intervening on the supply side? A recent strand of the literature tends to see overeducation/overskilling as consistent with, rather than in contrast to the human capital theory. In other words, overeducation would not be a signal of excess schooling, but rather of a lack of the work-related component of human capital, which makes it hard for firms to employ young graduates. Alternatively, overeducation could be consistent with the job competition model or of the strong competition for jobs in presence of a constant demand for skills that leads graduates to accumulate more and more education to an extent that is in some cases more than that requested to get a job.

Overall, the evidence provided in the paper is consistent with the hypothesis of a low demand for skills typical of the job competition explanations. Nonetheless, overeducation/overskilling is clearly strongly associated also with a very low quality of human capital, while being reduced by curricula including some work related skills. In other words, while increasing in the educational dimension, the human capital of Italian graduates does not sufficiently develop in terms of the competences which are directly requested in the labor market. In turn, this tends to reduce the ability of graduates to access high quality jobs and might hence suggest that there is a potential demand for job specific competences in the labor market which remains unexploited. Some injection of the German dual principle might hence be useful to reduce the educational mismatch.