If people become aware of their stereotypes, do they change their behavior? Stereotypes are over-generalized representations of characteristics of certain groups. They allow for easier and efficient processing of information, but they may cause biased judgment or even discrimination against particular groups. In addition, discrimination may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies by influencing the behavior of discriminated groups in the direction of the stereotypes.

A recent IZA discussion paper by Alberto Alesina, Michela Carlana, Eliana La Ferrara and Paolo Pinotti investigates how implicit stereotypes held by middle-school teachers in Italy bias their assessment of immigrant and native children. Based on a sample of 65 Italian middle schools, the authors investigate the magnitude of existing stereotypes and whether revealing these stereotypes to the teachers makes them reconsider their behavior.

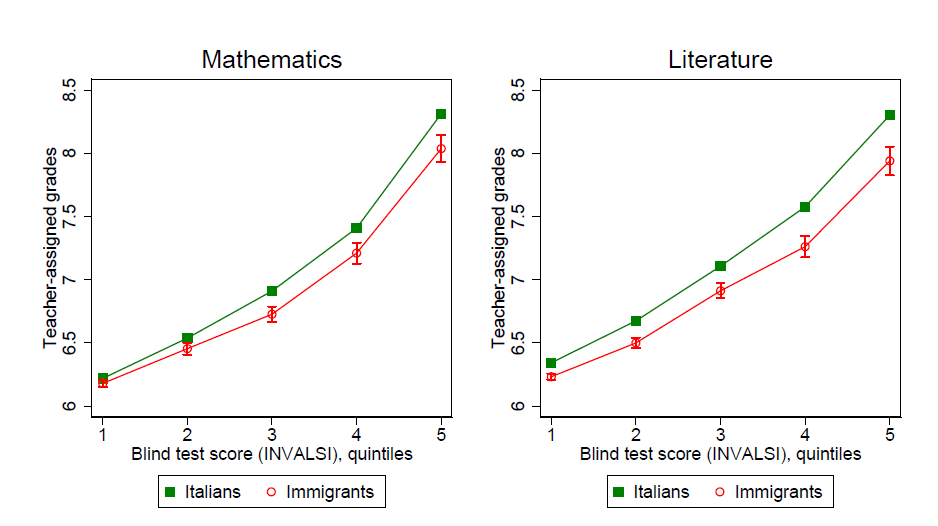

Students in Italy choose between different tracks after middle school. Discrimination at this important juncture may ultimately lead to poorer career outcomes. As Figure 1 shows, teachers in both Mathematics and Literature tend to give lower grades to immigrant students compared to natives who have the same performance on standardized, blindly-graded tests.

This mismatch per se is not a proof of bias, since there may be characteristics that differentiate immigrants from natives that are only observable to teachers, such as disciplinary problems. To prove that these differences indeed result from teachers’ stereotypes, the authors empirically assessed the extent to which teachers were biased towards immigrants in a so-called Implicit Association Test (IAT).

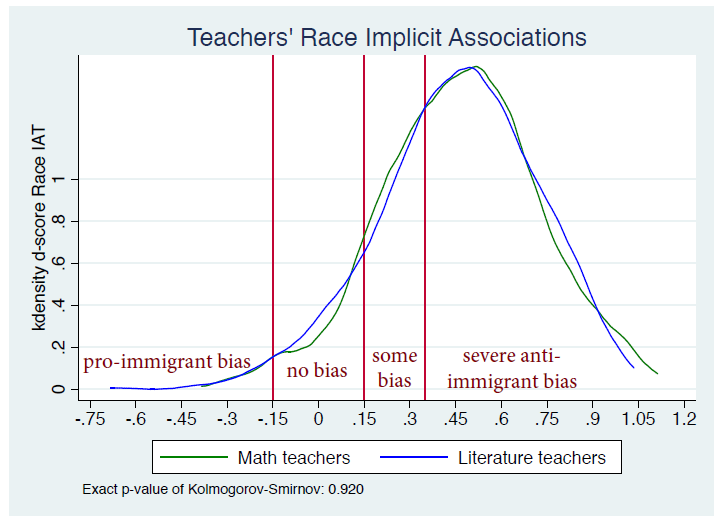

The IAT elicits hidden associations that may even be unknown to the individual taking the test. Teachers were shown immigrant-sounding and native-sounding names on the screen, along with a list of positive and negative attributes which they had to assign to these names. The stereotypes were then measured using the differences in reaction times when associating the attributes to the different names.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of raw IAT scores for Math and Literature teachers. The study finds that over 67 percent of the teachers held at least some negative stereotypes against immigrants and that male teachers were more biased than female teachers.

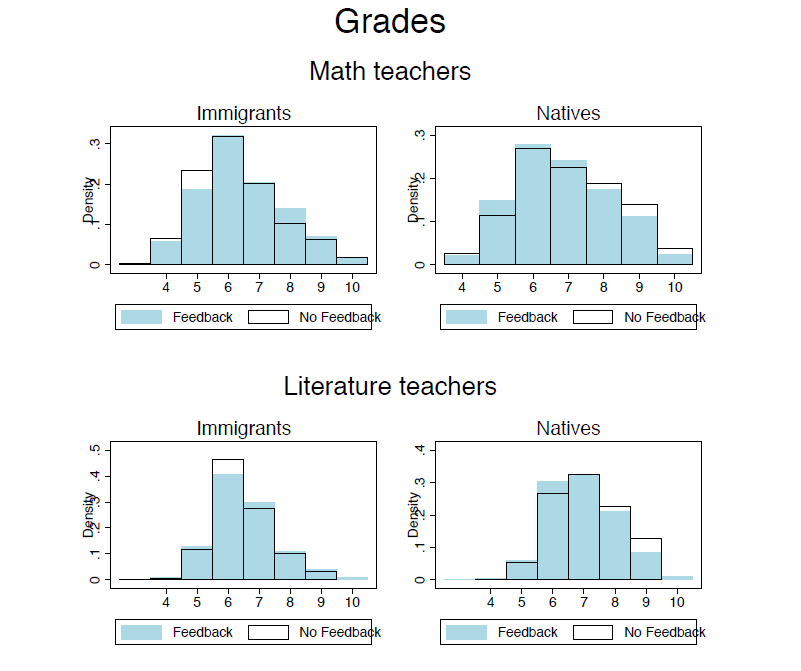

When teachers were informed about their held stereotypes shortly before grading, they gave higher grades to immigrant students compared to teachers who received feedback after, as long as their prior bias was not too strong. This implies that these teachers were not aware of their biased behavior because once it was revealed to them, they corrected it.

Figure 3 shows that grade distributions shift in favor of immigrant students after teachers were informed about their bias.

The results suggest that informing individuals of their own stereotypes might be an effective way to reduce discrimination. In the context of schools, the IAT can be a cost-effective way to test for biases. If teachers were asked to take the IAT periodically, it might help them become more cautious of their implicit biases, the study concludes.

However, the authors also stress that the implications of such a policy are not straightforward. By making teachers aware of their ‘implicit’ biases, their evaluation of students becomes more fair if they were acting upon their stereotypes by giving lower grades to immigrants. But it is possible that teachers whose negative stereotypes do not translate into discriminatory behavior may also react, thus inducing positive discrimination toward immigrant children.