In Germany, the poor performance in PISA 2000 stimulated a heated public debate and a strong policy response. Reacting to the low average and remarkable disparities registered by the test, the government implemented several educational reforms which improved the country’s educational performance and reduced the gap between children from advantaged and disadvantaged educational backgrounds. Between‐group achievement inequalities, however, still persist within the country. A new IZA Policy Paper by Goethe University Frankfurt researchers Maddalena Davoli und Horst Entorf takes a closer look at the policy reforms and the current situation.

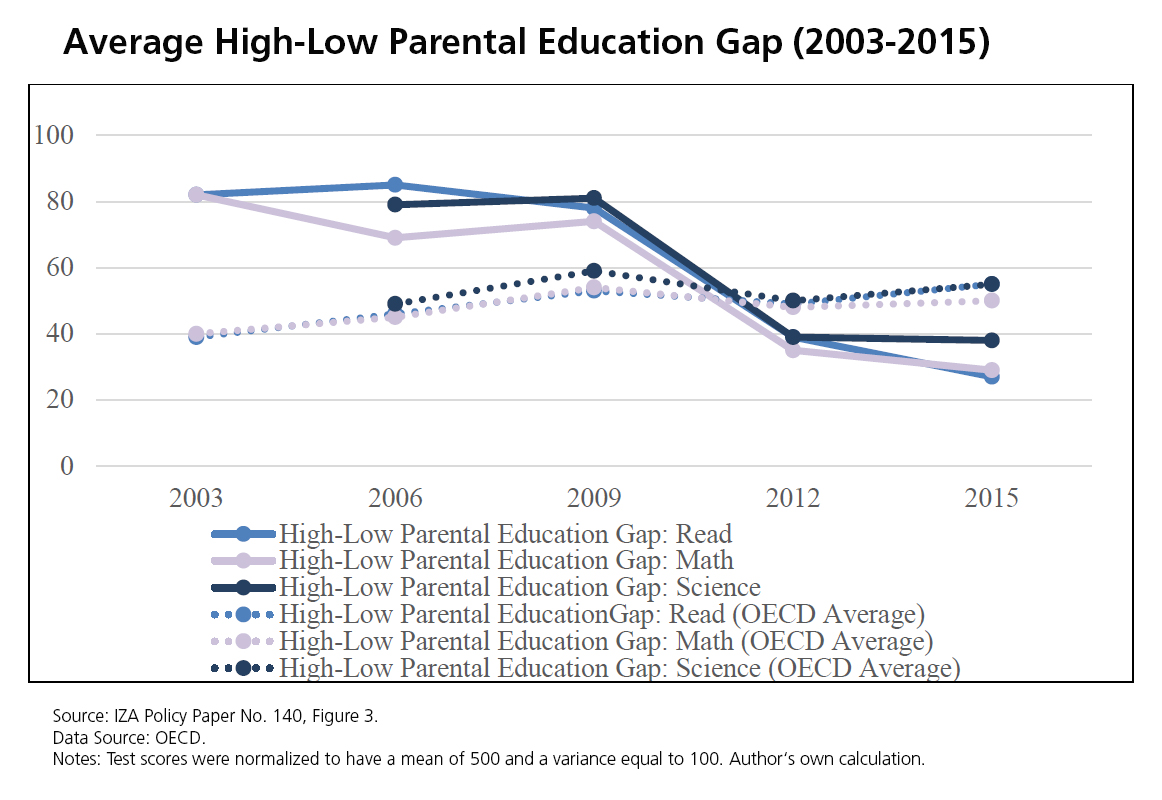

The reforms eventually led to a schooling system which has become more standardized and centralized, more closely monitored, and perhaps most importantly, less segregated than at the time before PISA 2000. The result of this change can be seen when looking at the performance difference of PISA scores between children from high vs. low educated parents: Whereas the disadvantage was significantly above the OECD average still in 2009, it fell well below the OECD average after the year 2012.

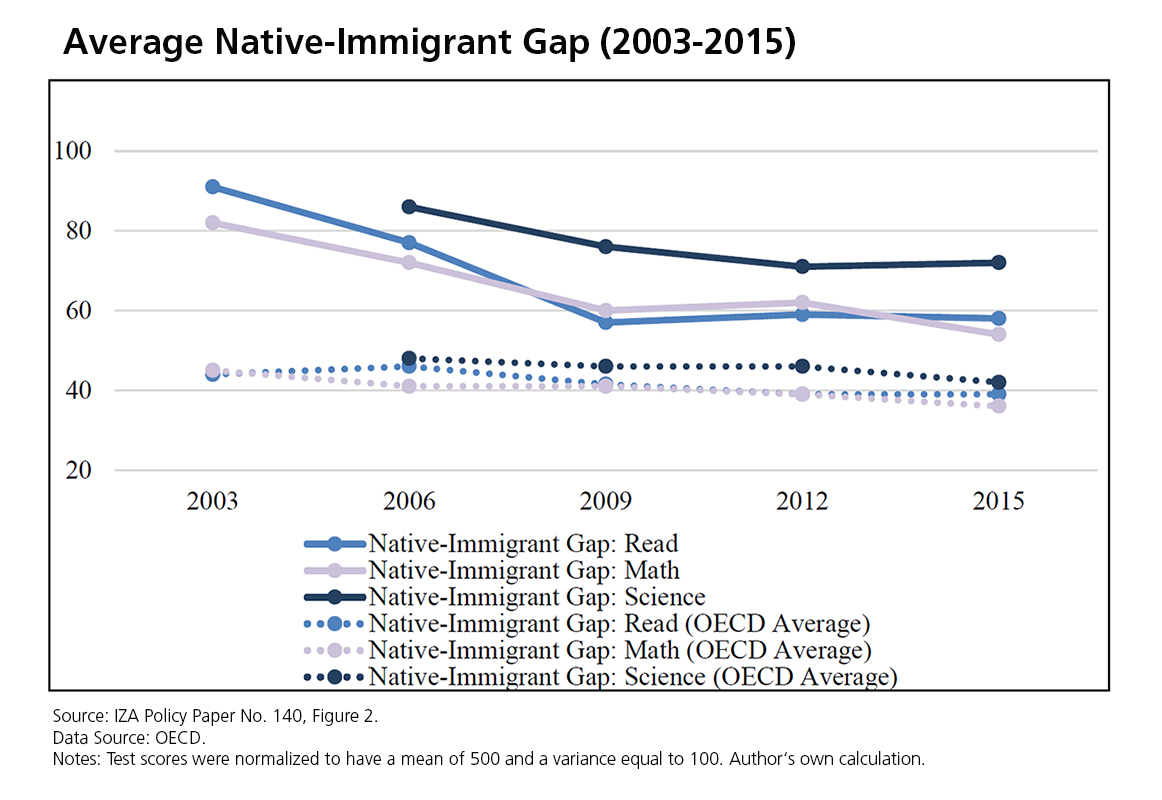

Still, children with a migratory history lag behind. Despite some improvements, the gap between native and immigrant children has remained above the OECD level.

The analysis identifies language problems as the major obstacle. In this respect, the common practice of early tracking restricts integration, as many of those with a poor command of the German language end up in the lower-track secondary schools (Hauptschulen), where they keep the peers speaking their mother tongue.

Controversy about the role of schools

Finally, although OECD’s PISA tests seems to be very successful, particularly in Germany, the authors also note that the OECD has been criticized for a potentially misleading impact of PISA tests as they may be biased in favor of the economic role of public schools. Critics claim that preparing children for gainful employment should not necessarily be the main goal of public education. Instead, students should be prepared for participation in democratic self‐government, moral action and well-being.

According to the authors, this critique is certainly an opinion which is not shared by the majority of German citizens and researchers working on education, but it represents the voice of a significant number of practitioners and educational scientists.