In 1980, China introduced the coercive one-child policy (OCP) which, as its name suggested, limited couples to having only one child. This was introduced by the Chinese government over concerns about overpopulation and economic growth. This policy lasted for more than three decades. The OCP was maintained through a system of fines, financial incentives, and intense propaganda.

Recent generations of Chinese women have grown up subject to this policy. Did exposure to such a restrictive policy and its influence in shaping a small-family culture permanently alter the subsequent fertility of Chinese women even after they were in an environment that did not restrict their fertility?

To answer this question, Siyuan Lin, Laura M. Argys and Susan L. Averett use data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to examine the childbearing decisions of a sample of Chinese women who migrated to the US after growing up for varying lengths of time exposed to the OCP. In the US, these migrants are free to have as many children as they want.

The new IZA discussion paper finds that Chinese women who immigrated to the US and were exposed to the OCP for a longer duration have significantly fewer children compared to similar women who were less exposed to the OCP.

Fertility preferences shaped by small-family culture

This is the case even when accounting for the woman’s natal family size in an attempt to disentangle the effect of growing up in a smaller family from the impact of OCP exposure to a small-family culture in shaping fertility preferences. The results are stronger for currently-married women and hold when using a sample of only Chinese women and when introducing a control group of women from other Asian countries/regions.

The negative impact of exposure to the OCP on fertility is evident even after controlling for patterns of fertility assimilation of migrants and education levels that might have increased due to the OCP. The authors’ estimates suggest that exposure to the OCP from age 6-30 results in about 7 percent fewer children than similar women who were not exposed to the OCP.

Dramatic consequences of strong son preference

The implementation of the OCP, while reducing fertility, has also had unintended consequences. Data from the World Bank show that the old-age dependency ratio, a critical indicator of strain faced by the younger generation to support the older generation, has risen dramatically in recent years. The OCP, enacted in a country with a strong son preference, has also been shown to lead to a skewed sex ratio resulting in a large proportion of unmarried men. In addition to altering the future family prospects of these men, some evidence suggests this imbalance has also led to an increase in crime.

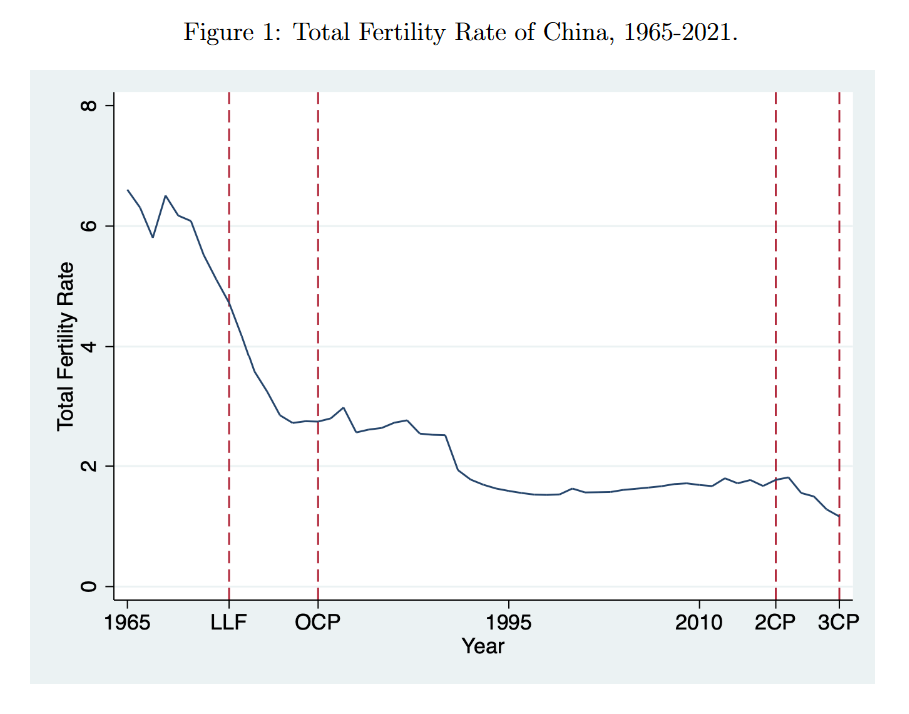

In response to concerns about the consequences of the low level of Chinese fertility and the recently declining population, the government enacted a two-child policy in 2016 that was quickly followed by a three-child policy in 2021.

New three-child policy unlikely to succeed

The finding that the duration of exposure to the OCP reduced subsequent fertility seems to be borne out by preliminary evidence from adopting the two-child policy in 2016. Despite eliminating penalties and encouraging families to have a second child through altered messaging, China’s TFR has continued to fall from 1.67 in 2015 to 1.28 in 2020. Clearly, fertility has not rebounded as policymakers had hoped, hence the enactment of the three-child policy in 2021.

The new research suggests that this policy has little chance of success since the vast majority of women currently of childbearing age in China were exposed to OCP messaging and penalties throughout most of their lives. It is unclear how long it will take to overcome decades of small-family cultural norms or if it is even possible, the authors write.