Many countries monitor their citizens using secret surveillance systems. According to the Democracy Index 2012, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, 37 percent of the world population lives in authoritarian states. In many of those countries, large-scale surveillance systems are installed that constantly monitor societal interactions and identify political opponents. Despite the prevalence of surveillance systems around the world, there is little empirical evidence on the social and economic costs of spying.

Many countries monitor their citizens using secret surveillance systems. According to the Democracy Index 2012, published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, 37 percent of the world population lives in authoritarian states. In many of those countries, large-scale surveillance systems are installed that constantly monitor societal interactions and identify political opponents. Despite the prevalence of surveillance systems around the world, there is little empirical evidence on the social and economic costs of spying.

In a new IZA Discussion Paper, Andreas Lichter, Max Löffler and Sebastian Siegloch aim to estimate the effect of state surveillance on social capital and economic outcomes by using official data on the regional number of spies in the former socialist German Democratic Republic (GDR). The official state security service of the GDR, the Ministry for State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit), commonly referred to as the Stasi, administered a huge network of spies called “unofficial collaborators’” (Informelle Mitarbeiter, IM). These spies were ordinary people, recruited to secretly collect information on any societal interaction in their daily life that could be of interest to the regime.

Correlation or causal effect?

Correlation or causal effect?

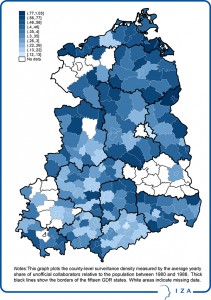

The authors use the substantial regional variation in the spy density across GDR counties (Kreise) to estimate the effect of surveillance on long-term outcomes of social capital and economic performance after the fall of the Iron Curtain and Germany’s reunification. The key challenge to isolate the causal effect of spying is to rule that the allocation of spies was driven by factors that also influenced social and economic outcomes after reunification.

The researchers address this challenge in two ways. First, they compare counties at GDR state borders. These counties were similar in observable characteristics except for the intensity of spying, which was (partly) administered by the Stasi offices at the state level. Second, they collect measures of social capital and economic performance from the 1920s and 1930s, hence prior to the existence of the GDR. In the econometric panel analysis, they use these pre-treatment data to demonstrate that the allocation of Stasi spies was not higher in regions that were traditionally more liberal, progressive or productive.

Trust in people and institutions is undermined

Overall, the authors find a negative and long-lasting effect of spying on both social capital and economic performance. Using data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), they show that more government surveillance leads to lower trust in strangers and stronger negative reciprocity – two measures that have been used as proxies for interpersonal trust in the literature. Moreover, they demonstrate that institutional trust, as measured by electoral turnout, is significantly lower in higher-spying counties. The findings imply that an abolition of all spying activities would have led to an increase in electoral turnout of 1.8 percentage points.

Other research has documented that trust in strangers is particularly important for entrepreneurs, given that it is very difficult to successfully run a business if people do not trust clients, trading partners or stake holders. In line with this mechanism, the IZA paper shows that self-employment rates as well as the number of patents per capita are significantly lower in higher-spying counties.

Economic slowdown and population decline

Last, the authors show that more general measures of economic performances are affected as well. Counties with a higher number of spies per capita experienced persistently higher unemployment rates post reunification. The authors further find significantly negative effects of the spy density on county population: Stasi spying appears to be an important driver of the tremendous population decline experienced in East Germany after reunification. For both out-migration waves (1989-1992, and 1998-2009), population losses were relatively stronger in higher-spying counties.

Overall, the paper documents that more intense state surveillance had negative and long-lasting effects on both social capital and economic performance. The findings are well in line with other studies on the relationship between the quality of political institutions, social capital and economic performance. While the study compares different East German counties to each other, it is likely that the findings are at least transferable to other countries of the former Warsaw pact that operated similar mass surveillance systems, such as Poland or the Czech Republic.