Religion and the traditional role model it conveys affects female labor market participation: Studies show that the likelihood of employment is lower for Catholic, Christian-Orthodox, and Muslim women compared to their Protestant peers. However, the influence of religious-conservative values may well change as society and economy transform. A changing society might imply changes in attitudes, or changes in child upbringing technology and household duties – either might pose internal and external restrictions on labor market access for married women.

Religion and the traditional role model it conveys affects female labor market participation: Studies show that the likelihood of employment is lower for Catholic, Christian-Orthodox, and Muslim women compared to their Protestant peers. However, the influence of religious-conservative values may well change as society and economy transform. A changing society might imply changes in attitudes, or changes in child upbringing technology and household duties – either might pose internal and external restrictions on labor market access for married women.

A new IZA paper by Justina A. V. Fischer and Francesco Pastore analyzes whether the impact of religious denomination on employment of married women in Europe differs a) by time period, b) over the female life cycle, and c) by cultural regions within Europe. Using the World Values Survey 1981-2013, the authors exploit information on 44,000 married women aged 25 to 60 years in about 40 countries. They distinguish between OECD and non-OECD countries to account for modernization and democratization processes in OECD countries.

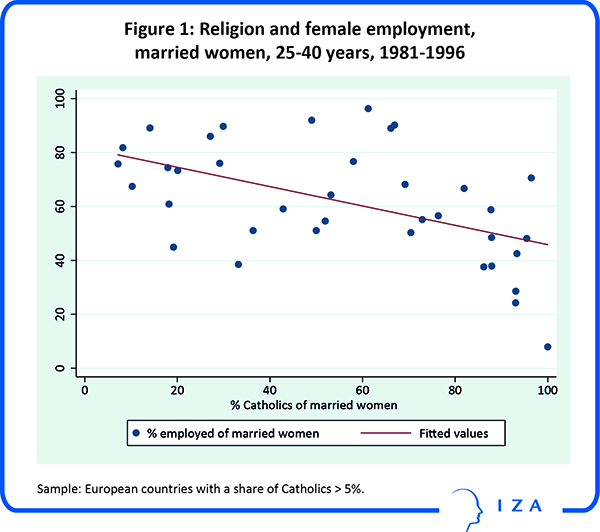

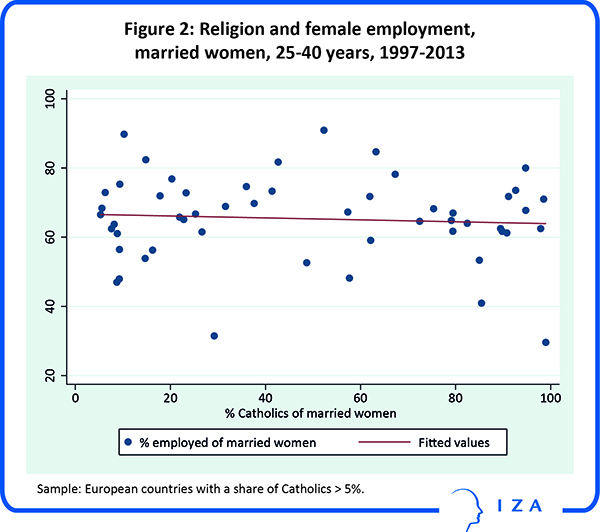

The two figures below provide a scatter plot relating female employment and distribution of religion in the female married population, aged 25-40 years: The share of employed is depicted on the Y-axis and the share Catholics on the X-axis; this correlation analysis is for those European countries only where there is a share of at least 5% of Catholics. Figure 1 refers to the period 1981-1996 and Figure 2 to the period 1997-2013. Inspection of the two figures shows that the sign of the correlation under consideration turns from negative in the first period to null in the second period.

The multivariate analysis shows that in European OECD member states the impact of religion on married women is not persistent, but vanishes over time: Behavioral differences by religion disappear during the more recent years (after 1996), for both young and old women likewise (except for Muslim wives).

In non-OECD Europe, however, even in recent times, religion still determines labor market participation of married women. This effect appears to be driven by women younger than 40 years. A possible explanation is the upbringing under communist regimes that promoted female labor market participation for ideological reasons. Only Muslim women are less likely to be gainfully employed, across all time periods, in both regions, across all life years.

In sum, cultural differences within Europe can possibly explain contradictory findings of various preceding studies. In a broader perspective, the analysis suggests that the impact of religion on female employment changes with a country’s history and institutions.