IZA was created in 1998 with a generous endowment from the Deutsche Post Foundation. Over the 20 years of its existence, IZA has issued nearly 12,000 Discussion Papers, touching on all areas of labor economics and labor issues, but also including studies dealing with appropriate statistical measurement, macroeconomic labor issues and many other areas related to labor. The IZA network of Research Fellows and Affiliates contains over 1,500 members from more than 60 countries. It includes many labor economists, but also specialists in labor issues in sociology and labor policy more generally.

Each year IZA has held or co-sponsored around 30 conferences covering such areas as education, migration, program evaluation, environmental issues and many others. It has also held an annual meeting, its Transatlantic Conference, bringing together one dozen researchers from each side of the Atlantic to exchange ideas and present their research. At the IZA Summer School, each year around 30 advanced European Ph.D. students discuss each other’s research, hear lectures on cutting-edge topics by world-renowned scholars, and, moreover, become acquainted with each other, fostering a cadre of European scholars of the next generation.

It seemed appropriate to commemorate these achievements by holding a large conference open to researchers from around the world. From over 600 submissions, 192 papers were selected and organized into 48 sessions on June 28-29 in Berlin. The World Labor Conference was also the venue for awarding the biennial IZA Prize in Labor Economics.

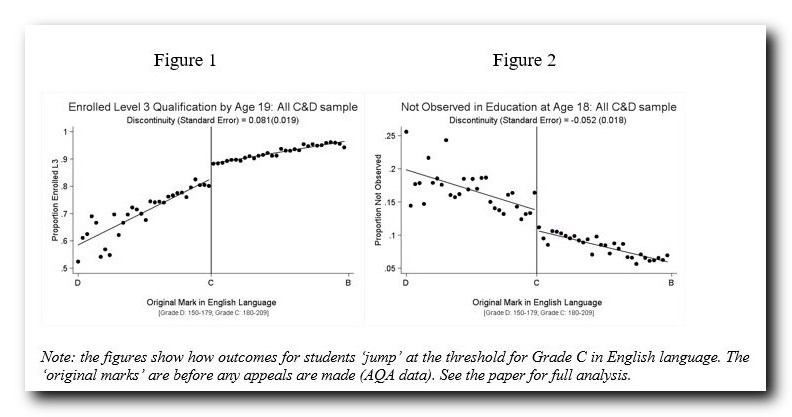

Further, narrowly missing a grade C increases the probability of dropping out of education at age 18 by about 4 percentage points (in a context where the national average is 12%) – illustrated in Figure 2. Those entering employment (and without a grade C in English) are unlikely to be in jobs with good progression possibilities.

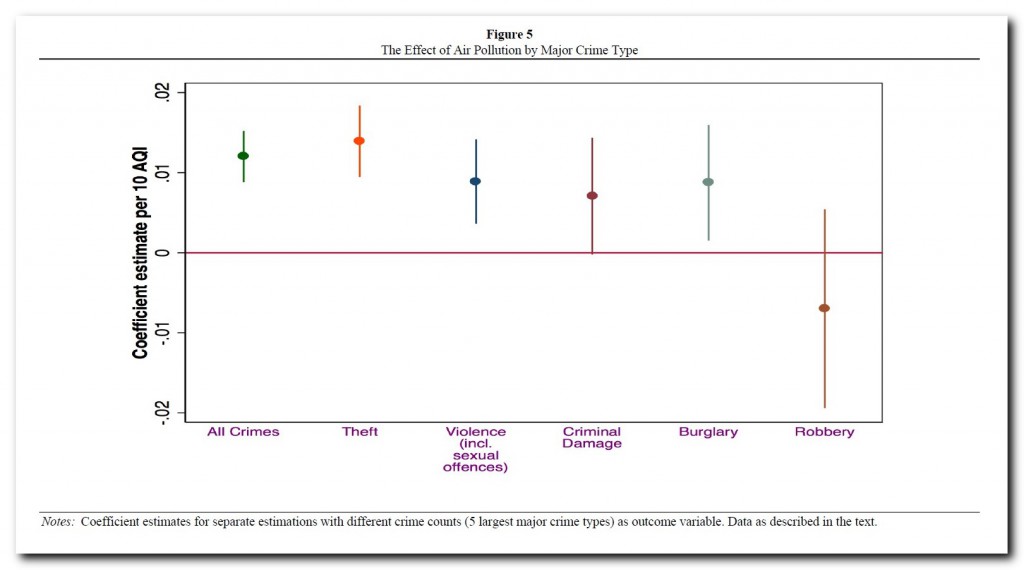

Further, narrowly missing a grade C increases the probability of dropping out of education at age 18 by about 4 percentage points (in a context where the national average is 12%) – illustrated in Figure 2. Those entering employment (and without a grade C in English) are unlikely to be in jobs with good progression possibilities. While they did not find that London’s ongoing spate of knife crime would be affected by improved air quality, the authors argue that the police could potentially be freed up to allocate more resources to these types of very serious incidents if the number of less serious crimes could be reduced. Given that the effect of air pollution on crime occurs at levels which are well below current regulatory standards in the UK and the US, it could be beneficial to lower these existing guidelines, according to the study.

While they did not find that London’s ongoing spate of knife crime would be affected by improved air quality, the authors argue that the police could potentially be freed up to allocate more resources to these types of very serious incidents if the number of less serious crimes could be reduced. Given that the effect of air pollution on crime occurs at levels which are well below current regulatory standards in the UK and the US, it could be beneficial to lower these existing guidelines, according to the study.

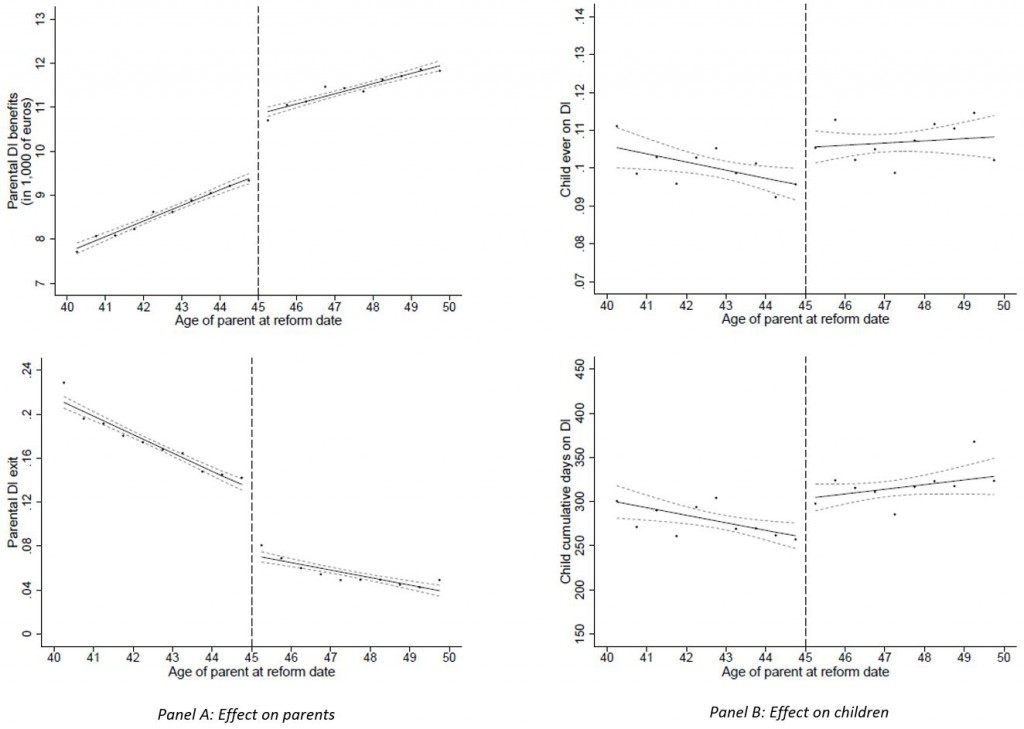

The findings show that more than 20 years after the reform, reduced parental DI dependency led to a lower DI dependency among children. Both the probability that a child is on DI as well as the benefits received from DI are substantially lower for those children whose parent’s DI use was reduced due to the reform (see Figure 1, Panel B). In addition, there are positive effects on future labor market outcomes for these children, with a higher employment rate and a higher level of labor market earnings. Consistent with an anticipated future with less reliance on DI, children of parents exposed to the reform invest in additional schooling while young.

The findings show that more than 20 years after the reform, reduced parental DI dependency led to a lower DI dependency among children. Both the probability that a child is on DI as well as the benefits received from DI are substantially lower for those children whose parent’s DI use was reduced due to the reform (see Figure 1, Panel B). In addition, there are positive effects on future labor market outcomes for these children, with a higher employment rate and a higher level of labor market earnings. Consistent with an anticipated future with less reliance on DI, children of parents exposed to the reform invest in additional schooling while young. Our behavior is strongly influenced by comparisons with others. These “others” are not usually assigned to us, but we choose who we interact and compare ourselves with. Or, as economists put it, individuals self-select into certain environments and into specific peer groups within given environments. However, little is known about the consequences of these self-determined choices.

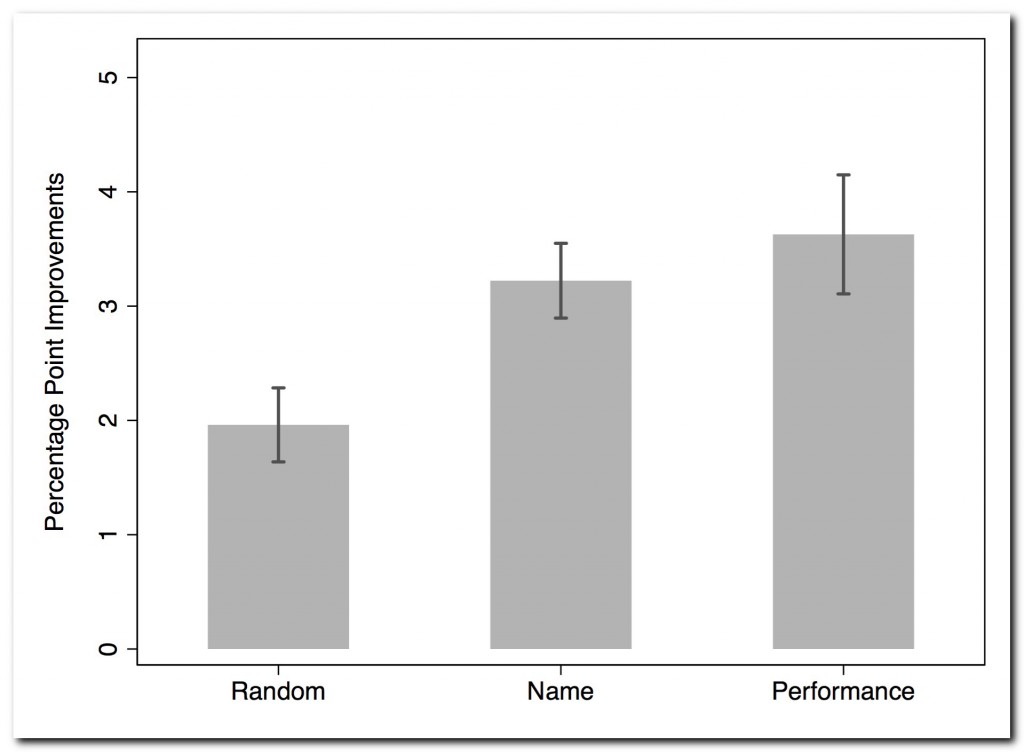

Our behavior is strongly influenced by comparisons with others. These “others” are not usually assigned to us, but we choose who we interact and compare ourselves with. Or, as economists put it, individuals self-select into certain environments and into specific peer groups within given environments. However, little is known about the consequences of these self-determined choices. The results show that the two peer-assignment mechanisms with self-selected peers improve average performance by 1.27–1.67 percentage points or .14–.15SD relative to randomly assigned peers.

The results show that the two peer-assignment mechanisms with self-selected peers improve average performance by 1.27–1.67 percentage points or .14–.15SD relative to randomly assigned peers.