The family environment is among the most important factors in the development of a child’s personality. It is evident that parental strategies and the amount of time and  resources that parents are able to put towards their children would have a strong impact. Nonetheless, there are several popular anecdotes and stereotypes about the vastly different characteristics of siblings based on which order they were born and the age gap between them.

resources that parents are able to put towards their children would have a strong impact. Nonetheless, there are several popular anecdotes and stereotypes about the vastly different characteristics of siblings based on which order they were born and the age gap between them.

But does it really matter if a child is the first born, a middle child, or the last? Is it also relevant for the development of the child how many years parents wait to have another baby? According to two recent IZA Discussion Papers, both factors – birth order and spacing – play a role in shaping adult personality traits.

Psychologists have long hypothesized that birth order could be related to differences in personality. First-borns are believed to be more responsible and focused on pleasing the parents, thus acting as a role-model for their younger siblings, while later-born children are thought to be more easy-going and sociable.

Personality traits related to success seem to decline with birth order

An IZA Discussion Paper by Sandra E. Black (University of Texas at Austin and IZA), Erik Grönqvist (IFAU), and Björn Öckert (IFAU) studies this relationship between birth order and personality traits among Swedish men whose personality was assessed when enlisting in the military. The researchers find evidence that the types of personality traits which are positively related to success in life decline with birth order. First-born children show higher emotional stability, greater persistence, more social outgoingness, and higher willingness to assume responsibility and take initiative.

Given the importance of such personality traits in the labor market, the authors analyze whether occupational choices display a similar pattern as well. Indeed, first-born children are almost 30 percent more likely than third-borns to be top managers, an occupation which tends to require higher non-cognitive abilities.

But what can explain such a consistent pattern of stark differences between siblings? The authors scrutinize a number of mechanisms that might be driving these results. While they eliminate biological factors as a potential culprit, the authors point to parents’ behavior as the primary influence. They find that parents invest less in children that are born later, especially in terms of how strictly they enforce rules and how much time they put into discussing and helping with school work. The researchers also note that sibling rivalry and parents’ adaptation to it play a role in shaping children’s personality.

Larger age gaps associated with negative personality traits

Similar to birth order, birth spacing, i.e., the difference in age between siblings, also affects personality traits. The IZA Discussion Paper by Bart H. H. Golsteyn (Maastricht University and IZA) and Cécile A. J. Magnée (Maastricht University) follows a large British cohort from birth until age 42, studying the effect of age gaps between siblings on personality traits of the youngest child in a two-child household.

Larger birth gaps indeed appear to be related to more disorganized behavior, more neuroticism, and more introversion. While the authors do not investigate the underlying elements responsible for these outcomes in detail, the results suggest that small birth gaps make it easier for parents to devote adequate time and resources to both children simultaneously. In addition to more attention provided by parents, siblings closer to each other may be more able to play and learn from one another.

Adverse childhood circumstances matter too

While these studies show that the order and timing of births clearly matter for personality development, the effect of events later in childhood should not be neglected. The IZA Discussion Paper by Jason M. Fletcher (University of Wisconsin-Madison and IZA) and Stefanie Schurer (University of Sydney and IZA) reveals that adverse childhood experiences are significantly and robustly associated with neuroticism, conscientiousness, and openness to experience, but not with agreeableness and extraversion.

Each of these papers reinforces the importance of the conditions and context of early childhood development in shaping an individual’s personality, which in turn affects long-term success in life.

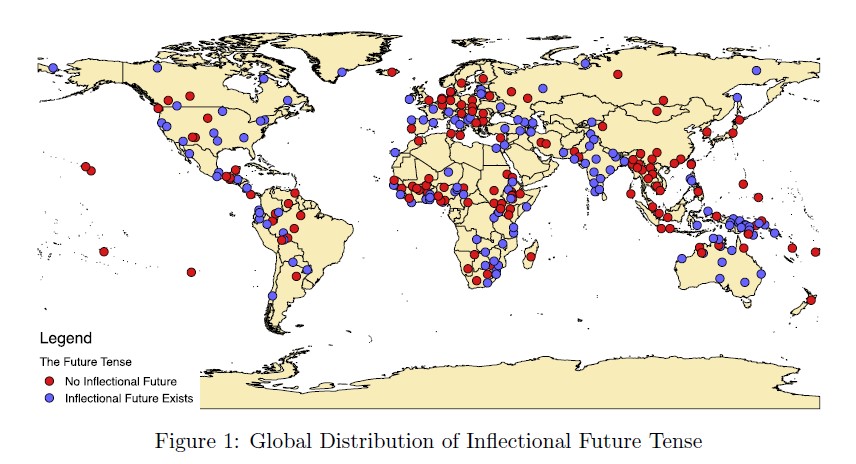

emigration countries fear that high-skilled workers will increasingly leave the country. Global migration flows indeed show a significant skill bias leading to a highly unequal distribution of global talent. Two IZA Discussion Papers analyze this development and contrast the problems of individual countries with the global benefits of migration.

emigration countries fear that high-skilled workers will increasingly leave the country. Global migration flows indeed show a significant skill bias leading to a highly unequal distribution of global talent. Two IZA Discussion Papers analyze this development and contrast the problems of individual countries with the global benefits of migration.

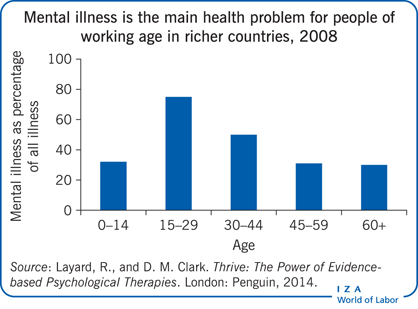

intertwined. People with poor mental health have lower levels of economic activity, lower earnings, and less stable employment. On the other hand, employment difficulties can undermine mental health; many who struggle to find meaningful work or who lose their jobs will experience poorer mental well-being as a result.

intertwined. People with poor mental health have lower levels of economic activity, lower earnings, and less stable employment. On the other hand, employment difficulties can undermine mental health; many who struggle to find meaningful work or who lose their jobs will experience poorer mental well-being as a result.

2008-2009 recession, followed by the sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone, and recent political developments which have seen the growth of anti-EU sentiments and extreme right-wing parties, even culminating in one Member State leaving with the Brexit referendum, the EU must come to terms with these phenomena by not only evaluating areas in need of potential reform, but also by effectively highlighting its successes.

2008-2009 recession, followed by the sovereign debt crisis in the Eurozone, and recent political developments which have seen the growth of anti-EU sentiments and extreme right-wing parties, even culminating in one Member State leaving with the Brexit referendum, the EU must come to terms with these phenomena by not only evaluating areas in need of potential reform, but also by effectively highlighting its successes. the story is far more complicated.

the story is far more complicated.

The UN has proclaimed February 20 the

The UN has proclaimed February 20 the