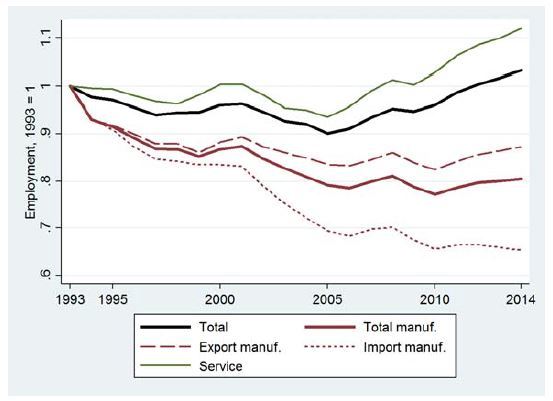

In the last 25 to 30 years, recoveries from recessions in the US have been plagued by weak employment growth. While before 1990 employment growth during the two years following a recession was a little over five percent, it has been just under one percent since then. One possible explanation for the slower recovery of jobs is related to technological change.

In the last 25 to 30 years, recoveries from recessions in the US have been plagued by weak employment growth. While before 1990 employment growth during the two years following a recession was a little over five percent, it has been just under one percent since then. One possible explanation for the slower recovery of jobs is related to technological change.

A 2012 landmark paper on job polarization in the US found that middle-skilled jobs, those usually involving routine tasks that are particularly susceptible to replacement by new technologies, may be destroyed permanently during recessions. The displaced workers from these jobs are then forced into time-consuming transitions to different occupations and sectors, resulting in slow job growth during the recovery.

This phenomenon of labor market polarization (or “hollowing out” of middle-skilled jobs) has attracted widespread attention and contributed to the ongoing debate on the impact of technological change on labor markets. While much of the focus has been on the United States, Georg Graetz (Uppsala University and IZA) and Guy Michaels (London School of Economics and IZA) investigate in their recent IZA Discussion Paper whether labor markets in other countries have also been slow to pick up after recessions, and if modern technology could be to blame.

“Jobless recoveries” a US phenomenon

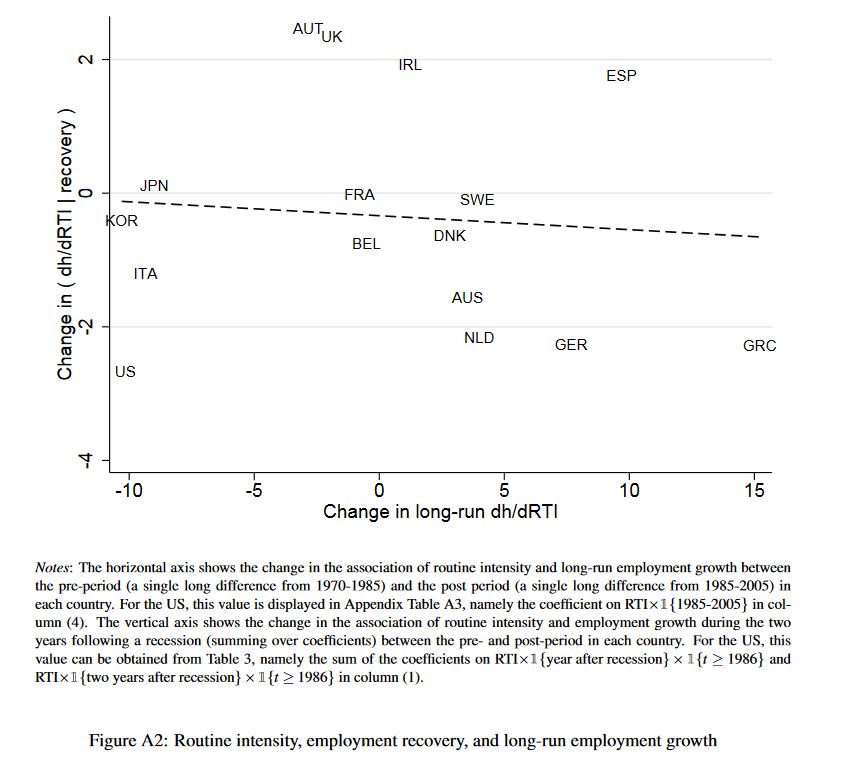

The authors analyze data from 71 recessions across 28 industries in 17 countries from 1970-2011 to first examine whether recoveries from recessions after 1985 produced slower employment growth than earlier recoveries. They then test if industries that are more susceptible to technological change have had particularly slow employment growth during recoveries. Finally, the researchers investigate whether routine-intensive industries have seen more replacement of middle-skill jobs during recessions and recoveries.

The results suggest that technology has not impeded job growth in recoveries outside the US. While GDP recovered more slowly after recent recessions in the countries under study, employment did not. Neither employment in industries more exposed to technological change nor middle-skilled employment experienced slower recoveries.

These findings pose a puzzle as to the nature of poor employment trends seen during recent recoveries in the US. Graetz and Michaels point to two possible explanations. The first is related to the differences in technology adoption found in previous studies. The second possible explanation appeals to US-specific policy and institutional changes: Unemployment benefit extensions, which increase workers’ reservation wages, may slow down employment growth during recoveries. Moreover, the declining role of unions may have facilitated the substitution of workers during recessions and recoveries. The authors stress, however, that further research is needed to establish the relative merits of the technology- and policy-based explanations.

photo credit: Maksim Dubinsky via Shutterstock

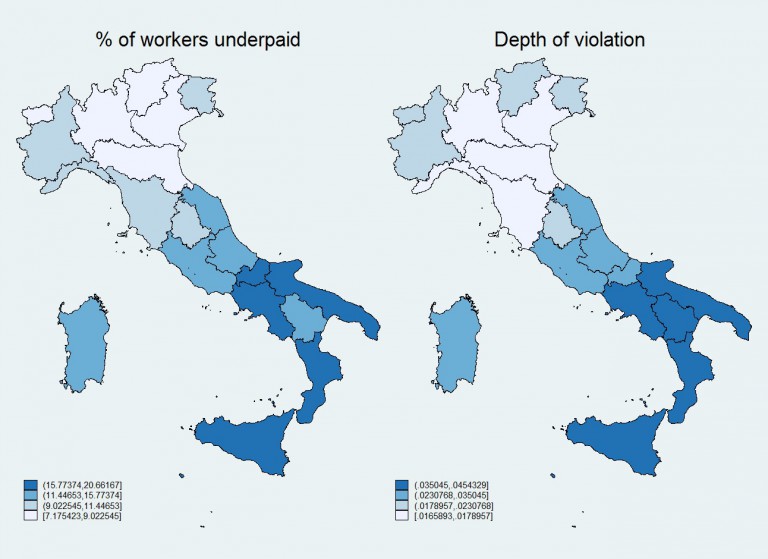

“Not surprisingly, non-compliance is particularly high in the South and in micro and small firms, and it affects especially women and temporary workers. Overall, the Italian collective bargaining system seems unable to safeguard a level playing field for firms and ensure that minimum wage increases are effectively reflected into pay increases for workers at the bottom of the distribution,” says Garnero.

“Not surprisingly, non-compliance is particularly high in the South and in micro and small firms, and it affects especially women and temporary workers. Overall, the Italian collective bargaining system seems unable to safeguard a level playing field for firms and ensure that minimum wage increases are effectively reflected into pay increases for workers at the bottom of the distribution,” says Garnero.

By relying on a rich matched employer-employee dataset from the social security records of the Italian region of Veneto, the authors investigate whether the employer of the acquiring company systematically shows preferential treatment for workers coming from the same hometown.

By relying on a rich matched employer-employee dataset from the social security records of the Italian region of Veneto, the authors investigate whether the employer of the acquiring company systematically shows preferential treatment for workers coming from the same hometown.

also a central theme during the U.S. presidential race. Donald Trump’s promise to deport “illegal immigrants” on a large scale was highly controversial, but this pledge touched a nerve with voters skeptical about the negative consequences of illegal immigration.

also a central theme during the U.S. presidential race. Donald Trump’s promise to deport “illegal immigrants” on a large scale was highly controversial, but this pledge touched a nerve with voters skeptical about the negative consequences of illegal immigration. raise living standards and lift people out of poverty, they contribute to gains in aggregate productivity, and they may even foster social cohesion.

raise living standards and lift people out of poverty, they contribute to gains in aggregate productivity, and they may even foster social cohesion.

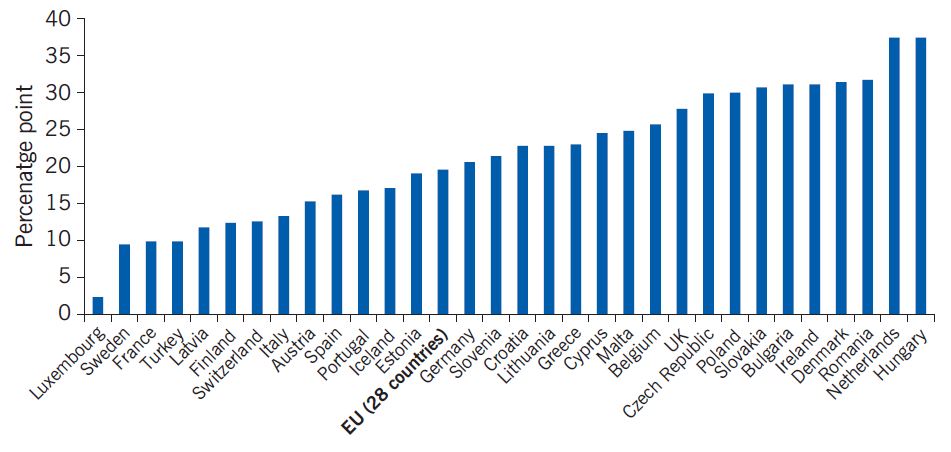

presence of a long-term limiting health condition. Despite the introduction of a range of legislative and policy initiatives designed to eliminate discrimination and facilitate retention of and entry into work, disability is still associated with substantial and enduring employment disadvantages.

presence of a long-term limiting health condition. Despite the introduction of a range of legislative and policy initiatives designed to eliminate discrimination and facilitate retention of and entry into work, disability is still associated with substantial and enduring employment disadvantages.