By Rafel Lalive, Camille Landais and Josef Zweimüller

University of Lausanne and IZA

The global crisis that erupted in 2008 has put millions of worker out of a job. The US, for instance, experienced an unprecedented increase in unemployment from around 4 percent to more than 10 percent during the Great Recession. Unemployment remained stubbornly even when the economy started to recover again.

Governments throughout the world have responded by making their unemployment insurance systems more generous (OECD, 2012). Some observers argue that US unemployment would have returned much faster to normal levels if the US had not expanded the duration of benefit payments from 26 to 99 weeks. Were UI extensions too generous? What is the optimal level of unemployment insurance (UI)? How much money should job seekers receive and for how long?

LSE

In theory, economists have a simple answer to these questions. UI should be set optimally, i.e. such that adding a dollar to UI generosity produces as much benefit as it costs (Baily 1978). But how does one go about finding the right amount of UI in practice? Actual policy needs to be based on sound evidence. Chetty (2008) discusses a new approach to finding the optimal amount of UI. The key idea of his “sufficient statistics” approach is to combine credible evidence on the benefits and costs of more generous insurance with a plausible theoretical framework to back out the optimal level of UI.

But, what is the evidence regarding the costs and benefits of UI extensions? The costs of more generous UI are the total costs to taxpayers. The total costs have two components: direct and additional. The direct costs are those paid to job seekers who exhaust their regular benefits. Additional costs arise because more generous benefits induce job losers to stay longer on UI benefits or enter unemployment more frequently. Interestingly, a growing number of studies give us well-identified measures of the costs at the individual level. Card and Levine (2000) find that adding 13 weeks of benefit payments will prolong the duration of benefit claims by about one week in the U.S. Since their data only cover unemployment spells until benefit exhaustion, the implied impact of extended benefits on total unemployment durations (including unemployment periods after benefit exhaustion) are larger. Lalive and Zweimüller (2004) find that 13 weeks of benefits prolong unemployment duration by one week for older workers in Austria. Lalive, van Ours, and Zweimüller (2006) discuss benefit level and duration and find that raising the benefit level is less costly than prolonging benefit duration.

Economists have spent less effort in estimating these benefits. UI benefits individuals if it helps to better smooth consumption between employment and unemployment. Gruber (1997) finds that job seekers experience a drop in consumption of 6 percent compared to when they were still employed. His estimates suggest that the drop in consumption would have been almost four times larger (22 percent) without UI. This study therefore shows that UI does what it is designed to do: insure people.

However, UI generosity does not only affect individual workers’ search effort, it may also affect the competition for jobs. The idea is simple: when generous UI induces all other workers to search less intensively, it become easier for me to find a new job. This means that optimal UI needs to account for search externalities. Existing studies on the effects of extending unemployment benefits do not take these externalities into account. If these externalities are empirically relevant micro studies miss an important part of the picture.

Landais, Michaillat & Saez (2013) provide a theoretical analysis of optimal UI in the presence of search externalities. They set up a search and matching model which shows that stronger search externalities increase the socially desirable generosity of UI. An important implication of this result is that UI should be more generous during recessions when jobs are scarce and externalities are strong. Conversely, UI should be less generous during booms when jobs are plentiful and externalities are weak.

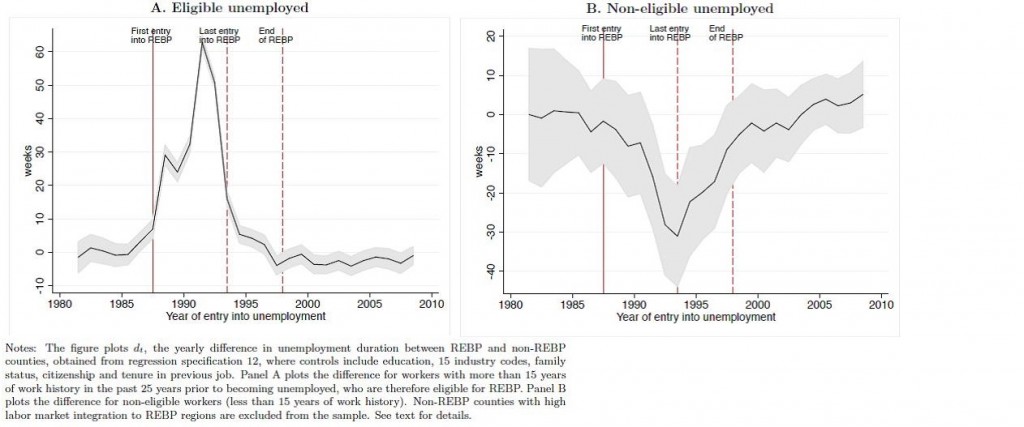

Yet are search externalities really empirically relevant? Lalive, Landais and Zweimüller (2013) provide evidence for search externalities in a quasi-experimental setting. They study a program that extended UI benefits from one to four years for certain workers in certain regions of Austria during the period 1988 to 1993. They show that this massive benefit extension led to a substantial increase in unemployment durations among eligible job seekers (Figure 1A). It also led to a substantial reduction in unemployment durations among non-eligible job seekers (Figure 1B). This evidence indicates that the effects of benefit extension programs on overall unemployment will be smaller than suggested by existing micro studies. Benefit extension programs reduce competition for jobs. Since the program induces eligible job seekers to search less hard, non-eligible job seekers face lower competition and find jobs more easily.

Interestingly, recent studies conclude that the US benefit extension programs of the Great Recession increased unemployment significantly but by less than half a percentage point (Rothstein 2011; Farber and Valletta 2013). This evidence suggests that the UI extensions in the US were less costly than previously thought.