The characteristics of potential classmates are among the decisive factors for parents when choosing a school for their child. It is commonly believed that children learn and achieve more when surrounded by high-ability classmates. In their new discussion paper, IZA researchers Benjamin Elsner and Ingo Isphording explore a channel that runs counter to the positive impact of high-ability peers: a student’s ordinal rank in her peer group. Smart students who have a low relative ability compared to their peer group – small fish in a big pond – may erroneously conclude that they have a low absolute ability and, thus, under-invest in their human capital.

The characteristics of potential classmates are among the decisive factors for parents when choosing a school for their child. It is commonly believed that children learn and achieve more when surrounded by high-ability classmates. In their new discussion paper, IZA researchers Benjamin Elsner and Ingo Isphording explore a channel that runs counter to the positive impact of high-ability peers: a student’s ordinal rank in her peer group. Smart students who have a low relative ability compared to their peer group – small fish in a big pond – may erroneously conclude that they have a low absolute ability and, thus, under-invest in their human capital.

Consider the following thought experiment: Jack and Jim have the same absolute ability, but a different rank in their respective high school cohort. Jack is among the students with the lowest ability in his cohort, while Jim is among the brightest students in his cohort. In other words, Jim is a big fish in a small pond. Is Jim more likely than Jack to finish high school, attend college, and complete a 4-year college degree?

To answer this question, the authors set up a quasi-experiment. Students are ranked according to their relative cognitive skills in their high-school cohort. Given that within the same school some cohorts have brighter students than others, two students with the same level of absolute ability will end up in a different rank in different cohorts. Comparing equally able but differently ranked students across cohorts within the same school allows isolating the effect of the individual rank.

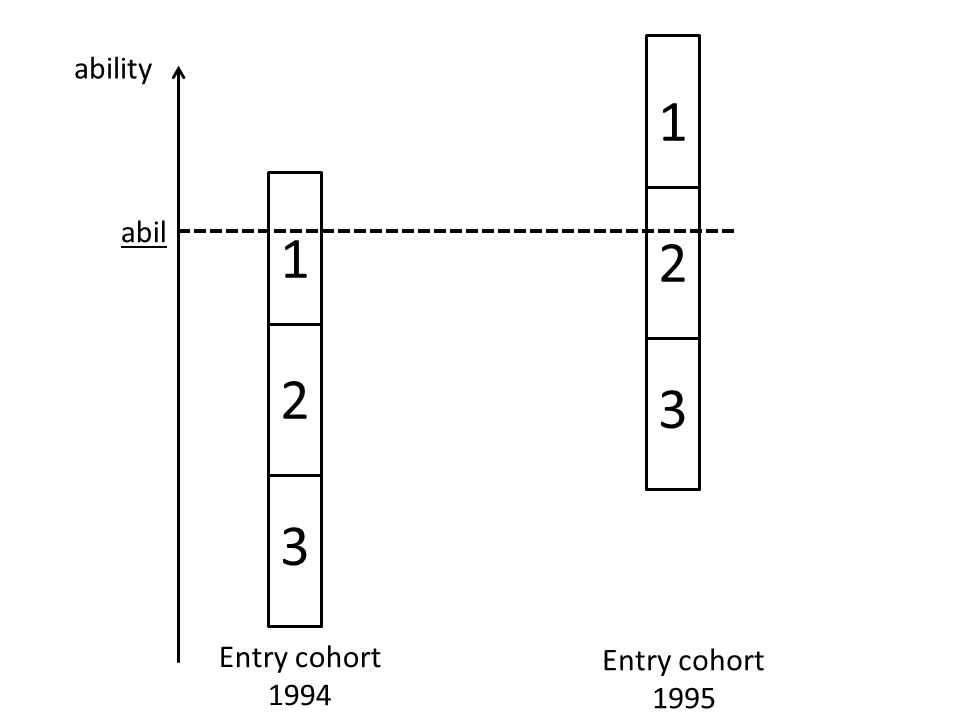

Figure I illustrates the basic idea: Two students of same cognitive ability abil enter school in two different cohorts, where students are ranked according to this ability. With ability abil, the student in entry cohort 1994 will be ranked among the upper third of his grade. Contrary, as the entry cohort of 1995 has a higher average ability, a similar student will only be ranked among the medium third.

Figure I illustrates the basic idea: Two students of same cognitive ability abil enter school in two different cohorts, where students are ranked according to this ability. With ability abil, the student in entry cohort 1994 will be ranked among the upper third of his grade. Contrary, as the entry cohort of 1995 has a higher average ability, a similar student will only be ranked among the medium third.

The central finding of the study is that a student’s ordinal rank in a high school cohort has a strong impact on educational outcomes later in life. The difference between the 10th- and the 20th-best student in a cohort of 100 students increases the probability of high-school completion by half a percentage point, and increases both the probabilities of college attendance and 4-year-degree completion by one percentage point.

What is driving this effect of rank on educational attainment? Further results indicate that highly-ranked students perceive themselves as more intelligent, are more optimistic, and have higher expectations to go to college when they are young. Further, they also feel (and potentially are) better supported by their teachers.

The paper shows that social comparisons affect the decision to invest in further education, and suggests that students who are smart in absolute terms but have a low rank in their cohort – small fish in a big pond – deserve special attention in the education system.