Few topics in labor economics have received more attention in academic, public and policy debates than the gender pay gap. The IZA Newsroom frequently summarizes new research findings on various drivers of the gap, including the role of discrimination vs. structural differences, or gender differences in wage expectations. Three recent IZA papers have looked into gender differences in quit behavior, job satisfaction, and job preferences – or, more broadly speaking, why women tend to be less pay sensitive than men.

Why men quit and women stay when pay is low

It has long been documented that men are more likely than women to quit their jobs for better pay at another firm. This contributes to the gender wage gap because firms need to pay their male employees relatively more to keep them on board. A new IZA discussion paper by Christian Bredemeier, based on data from a large U.S. household survey, shows that almost all of the gender difference in job quitting behavior can be attributed to gender differences in household earner roles rather than risk aversion or other psychological factors.

“When offered a job that pays, say, 5% more than the current job but is less likeable in terms of other characteristics such as location or working hours, the importance of this 5% pay difference depends on how strongly the household relies on the earnings of the considered individual,” says Bredemeier. As long as men are still the primary earners in most households, the non-pay dimensions of their jobs will receive relatively little weight.

The results thus suggest that firms discriminate by earner status rather than against women per se when they pay men more to keep them from quitting. Since this practice reinforces and perpetuates pay differences between men and women, policies promoting gender equality in the household could play an important role in closing the gender pay gap.

Why women are more satisfied with their jobs

There has been much debate about why a gender gap also exists in job satisfaction, even when a wide range of personal and job characteristics are controlled for. One often cited argument is that women may have lower expectations than men, and therefore report higher satisfaction, even in jobs that may be objectively worse.

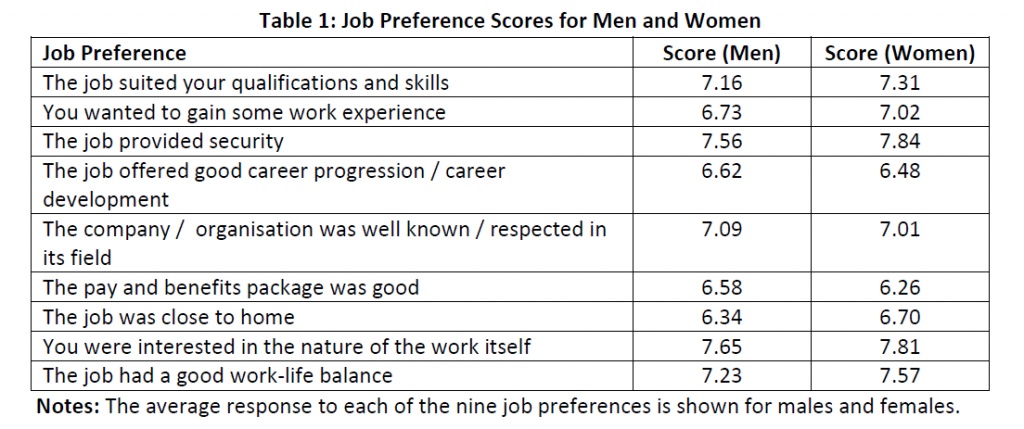

However, using unique data for Europe which captures detailed preferences relating to an employee’s job choice (see table below), an IZA discussion paper by Paul Redmond and Seamus McGuinness shows that job preferences explain much of the gender gap in satisfaction.

Two preferences stand out as particularly important: intrinsically liking the work and having a good work-life balance. These preferences are strongly associated with greater job satisfaction and women place a greater emphasis on both of these factors than men. Controlling for these preferences causes the gender gap in job satisfaction to disappear.

Why women are overrepresented in the public sector

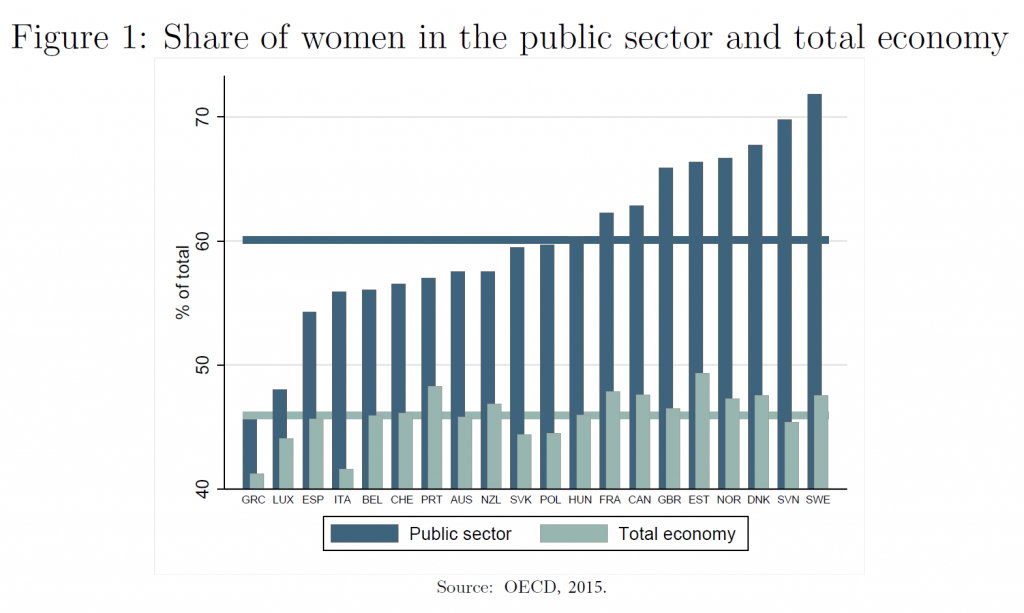

Gender differences in job preferences may also explain why in most countries women are overrepresented in the public sector (see figure). A recent IZA discussion paper by Pedro Maia Gomes and Zoë Kuehn quantifies for four countries how much of the selection of women into the public sector is driven by lower gender wage gaps, better work-life balance, greater job security, or intrinsic preferences for public sector activities.

The authors find that women’s preferences explain 20 percent of the gender bias in France, 45 percent in Spain, 80 percent in the US, and 95 percent in the UK. The remaining bias is explained by differences in public and private sector characteristics, in particular relatively higher wages for female public sector workers that explain around 30 percent in the US and Spain and 50 percent in France. Work-life balance is found to be an important driver only in France and Spain, explaining 20 to 30 percent of the gender bias.

Calculating how much of their wages private sector workers would be willing to sacrifice to face the same job separation rates or working hours as workers in the public sector, the authors find that the work-life balance premium is very high in Spain (25 to 36 percent), high in France and the UK (7 to 15 percent) and lower in the US (7 to 9 percent).

In all countries, the job security premium is much lower, ranging from 1-2 percent in the US and the UK to 3-4 percent in France and Spain, countries with higher unemployment rates. Regarding gender differences, the study finds that women are willing to pay more for work-life balance, while men are willing to pay more for job security. Higher job security in the public sector thus actually reduces the gender bias. This is due to the fact that women in general have a higher “opportunity cost” of working, as well as lower wages, which makes job losses more painful for men.

+++

For related research see also the IZA World of Labor key topic page: “What is the gender divide?”