In January 2016, China formally changed its one-child policy, now allowing all couples to have two children. Fei Wang, Liqiu Zhao and Zhong Zhao systematically examine the labor market consequences of China’s family planning policies in their recent IZA Discussion Paper. Their simulation results indicate that the new two-child policy may be too little, too late to alleviate the aging problem in China.

In January 2016, China formally changed its one-child policy, now allowing all couples to have two children. Fei Wang, Liqiu Zhao and Zhong Zhao systematically examine the labor market consequences of China’s family planning policies in their recent IZA Discussion Paper. Their simulation results indicate that the new two-child policy may be too little, too late to alleviate the aging problem in China.

China’s family planning policies are one of the most fundamental social policies in China. This assemblage of policies is much more complex than the simplified notion of a one-child policy. While the Chinese government initiated family planning policies in 1962, the well-known one-child policy had only been implemented since 1980.

Even after 1980, there were considerable regional and ethnic variations as well as many changes, notably the exemption of ethnic minorities and the relaxation of the strict one-child policy in rural China in the mid-1980s. As of January 1, 2016, all Chinese couples are now allowed to have two children. These policies have a far-reaching impact on many aspects of society, including the Chinese labor market.

Effects on age and gender composition of the working-age population

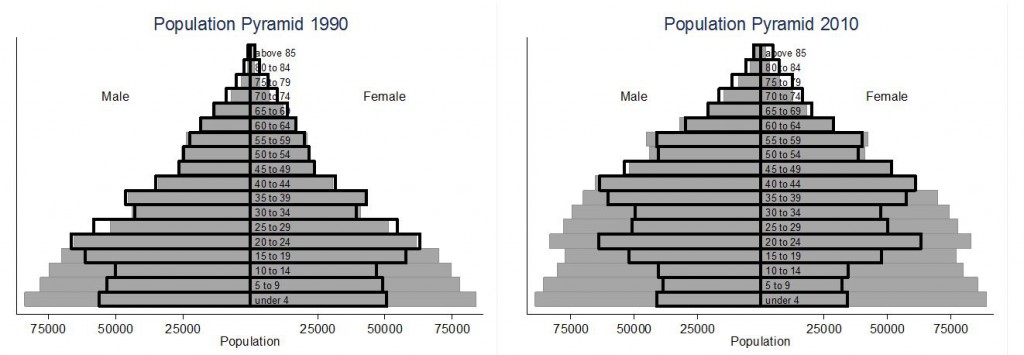

The dramatic drop in the total fertility rate during the 1970s has resulted in reduced numbers of people newly entering the workforce from the 1990s and beyond. Figure 1 presents factual and counterfactual population pyramids for the male and female populations in 1990 and 2010. The unfilled bars with black lines refer to the factual population pyramids. The gray bars denote the pyramids under the counterfactual regime in which no family planning policies take place, i.e., no “Later-Long-Fewer” family planning campaign and one-child policy. As can be seen, the factual pyramids show a low number of births between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s.

The working-age population (15 to 64 years) was 973.3 million in 2010, which accounted for 74.5% of the total population. The share of the working-age population peaked in 2010 and started to decline afterwards. This declining labor force growth has caused labor shortages and thus has increased wages. On the contrary, the counterfactual age structure is pyramid-shaped with a broad base of young generations, indicating that China’s working-age population would not have shrunk without family planning policies.

Another key feature of the evolution of the working-age population is the skewed sex ratio of the working-age population as people born after the enactment of the one-child policy in 1979 enter the workforce in the late 1990s. The male-biased sex ratio may lower female labor force participation as a high sex ratio increases the shadow wage for home production.

Interaction of family planning policy and internal migration

The age structure of a region is shaped not only by the processes of fertility and mortality, but is also importantly impacted by migration. With respect to the first two, the family planning policy has been implemented more rigorously in urban areas and areas with a high proportion of Han ethnicity, which would be expected to result in a more rapid aging process in these areas.

The interaction of the family planning policies and migration in China, however, has reversed the trend of regional aging rates. Regions with more stringent enforcement of the family planning policy have lower fertility rates and thus a lower supply of local native workers. Other things being equal, these regions, therefore, have a higher demand for migrant workers.

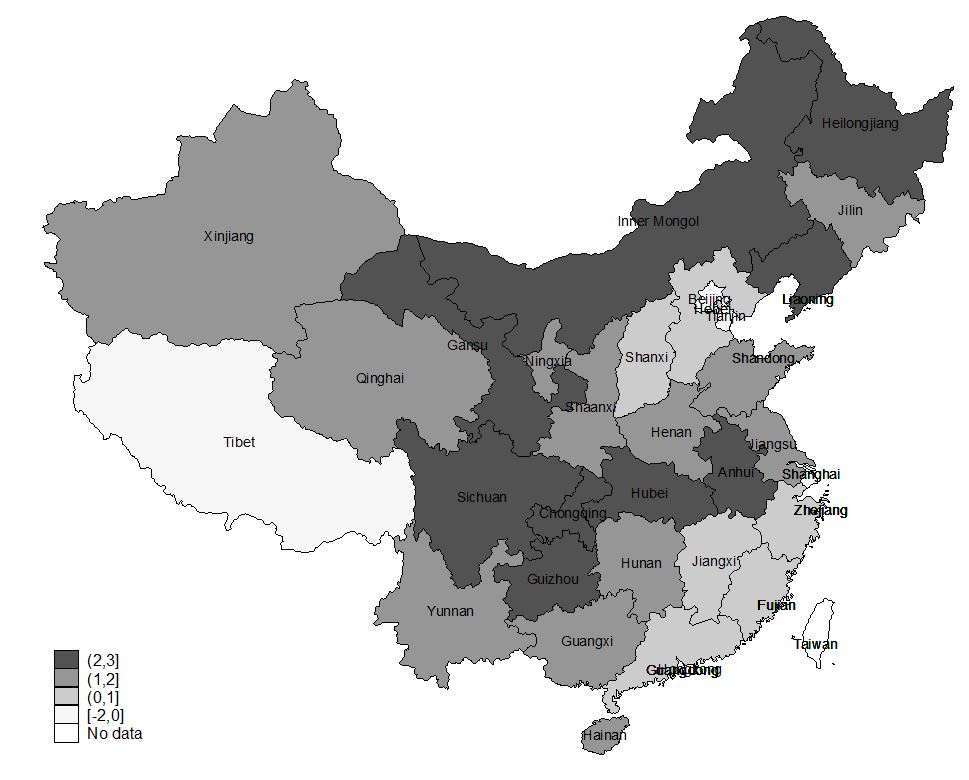

Thus, the strict enforcement of family planning policies in urban areas has accelerated rural-to-urban migration. In addition, the types of migrants that have moved to cities for work are mostly young, as can especially be seen in eastern coastal China and the major urban centers, such as Guangdong and Zhejiang province. This internal migration has, in turn however, led to a more serious aging challenge in the typically more rural and inland provinces, such as Sichuan and Anhui province.

As shown in Figure 2, the proportion of the population aged 65 and over increased by more than 2.5 percentage points in Anhui, Gansu, Guizhou, Sichuan and Chongqing over the period 2000-2010, while this number actually decreased in Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin and only increased by less than 0.5 percentage points in Zhejiang and Guangdong.

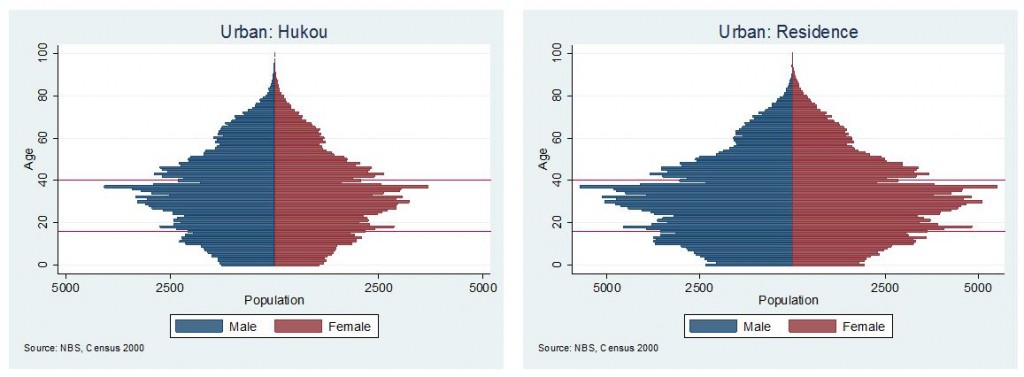

The left panel of Figure 3 presents the population pyramids for the urban hukou population (excluding migrants) for the year 2000. The urban hukou pyramid is diamond-shaped, indicating a shrinking urban hukou population beginning at the time of the one-child policy. However, when migrants are included (right panel), the pyramid for the urban residents has a wider base ,indicating that the internal migration of young laborers has shifted the aging problem from urban to rural areas.

These results highlight the greater challenge faced by rural areas and inland provinces to overcome the aging problem because rural areas and inland provinces are usually less developed, have less resources for social security, including old-age support, and have been losing their prime-age population to the urban areas and coastal provinces.

The new two-child policy

Already beginning in 2014, almost all provinces allowed a couple to have a second birth if one spouse is an only child. Since people born in the 1980s and early 1990s under the one-child policy played a major part in childbearing, there were 11 million couples who qualified for a second birth. By September 30, 2015, approximately 1.85 million couples had applied for birth certificates for a second birth, comprising a proportion of only 16.8%. This implies that the two-child policies are unlikely to increase fertility sharply, at least when one partner is an only child, which will be more common in the future.

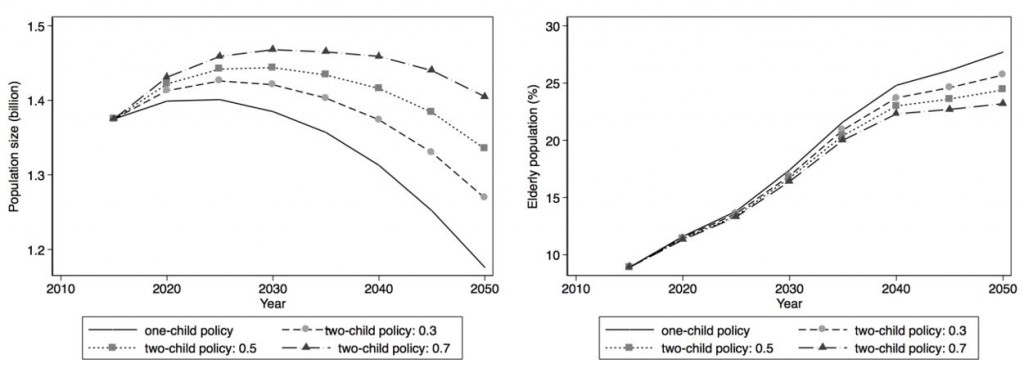

Through simulation, Fei Wang, Liqiu Zhao and Zhong Zhao investigate if the new two-child policy will be able to alleviate the aging problem in China. The left panel of Figure 4 shows how China’s population size would evolve under the two-child policy versus under the one-child policy. This panel assumes three different effects of the two-child policy on women’s lifetime number of births compared to the previous one-child policy: an increase of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7 children; with 0.3 being around the estimates in the literature. This panel implies that the two-child policy could, to some extent, temporarily increase the population and labor force until it begins shrinking around 2030.

The right panel of Figure 4 shows the proportion of the population aged 65+ over time under the one- and two-child policies with the same levels of fertility effects. It is clear that the two-child policy is far from pulling China out of aging.

No birth control and pro-natal policies

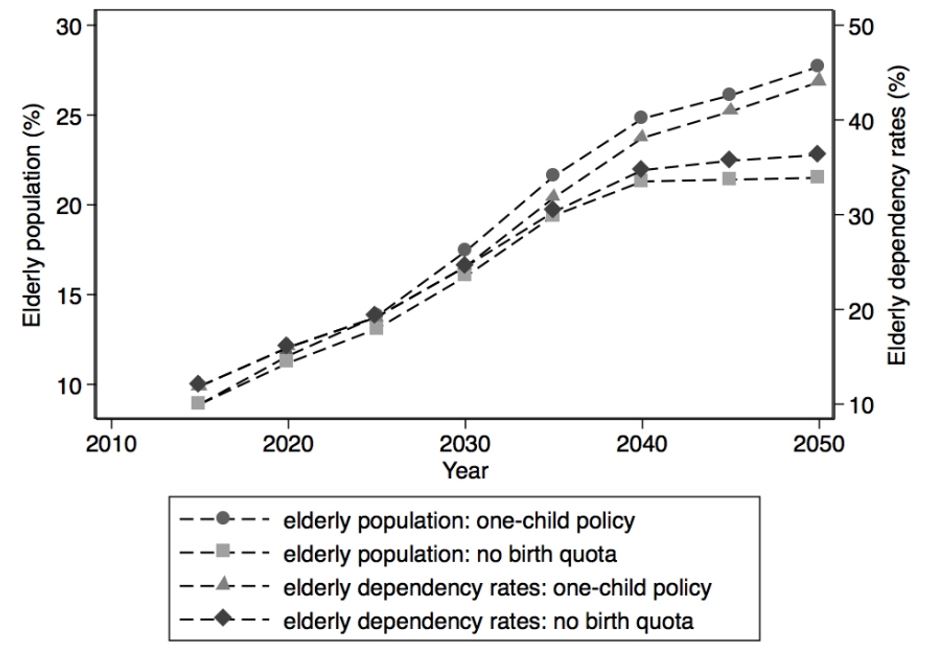

Assuming that removing the birth quota would lead to a lifetime fertility increase by 1, which is a radical estimate given the experience of some East Asian countries, Figure 5 simulates how the percentage of the elderly population and the elderly dependency rates would change over time had the birth quota been absent since 2015, compared to the one-child policy. While abolishing the birth quota would better address the aging problem than the two-child policy, it still may not be enough.

Elderly dependency rates

Although it is impossible to predict China’s population and labor market effects under birth encouraging policies without knowing the specific policy forms, the authors discuss the possible implications based on knowledge from pro-natal policies in other East Asian countries/regions such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. While Japan and Singapore’s policies have existed for more than 20 years, and more time may be needed for evaluating the more recent policies in South Korea and Taiwan, all of these policies thus far have not shown significant effects on fertility.

If pro-natal policies fail to increase fertility rates and other measures such as opening borders to international immigrants are not implemented in China, the population would inevitably continue to age, and labor markets may encounter a shortage in the workforce if the industrial structure simultaneously fails to transform properly.

The authors therefore call on China to learn the lessons from their other neighboring countries/regions and take action as soon as possible, or it could be too late since the fertility rates have already been at low levels for such a long time.