The misfortune of being born – or graduating – in a recession can have long-term consequences for people’s life outcomes that extend beyond economic disadvantage. Two recent IZA discussion papers highlight the adverse health effects ranging from lower birthweight to higher mortality.

Graduating in a recession

Entering the labor market in a recession worsens lifetime outcomes of young workers through no fault of their own. Research has long established that poor job prospects at the time of graduation may result in permanent income losses (see the IZA World of Labor for an overview).

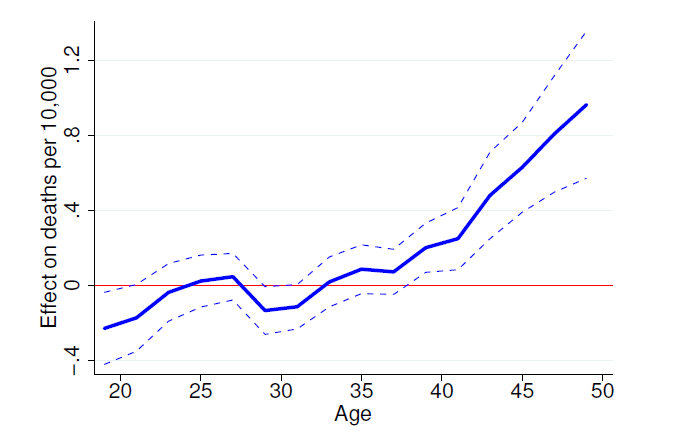

A new paper by Hannes Schwandt and Till von Wachter shows that this also affects mortality in midlife. Using several large cross-sectional data sources, the authors find that cohorts coming of age during the deep recession of the early 1980s suffer increases in mortality that appear in their late 30s and further strengthen through age 50 (see figure below).

These mortality impacts are largely driven by disease-related causes such as heart disease, lung cancer, and liver disease, as well as drug overdoses. At the same time, unlucky middle-aged labor market entrants earn less and work more while receiving less welfare support. They are also less likely to be married, more likely to be divorced, and experience higher rates of childlessness.

The findings of the study thus demonstrate that temporary disadvantages in the labor market during young adulthood can have substantial impacts on lifetime outcomes, can affect life and death in middle age, and go beyond the transitory initial career effects typically studied.

Children of crisis

But the role of luck comes into play already much earlier in life – even before birth. Using Turkish survey data, a new study by Mevlude Akbulut-Yuksel, Seyit Mumin Cilasun and Belgi Turan shows how newborns suffer from expectant mothers’ exposure to a severe economic crisis.

The authors explore the deep crisis of the Turkish economy between 2001 and 2008 and use regional variation in the crisis impact to analyze the effects on newborns, compared to their siblings. The findings reveal that regional GDP contributes significantly to better birth outcomes among crisis-time children, in terms of lower probability of low birthweight, less premature births and a longer pregnancy duration.

Adverse health effects are mainly observed among children born to mothers with low socio-economic status, which suggests that credit constraints play a major role.

Since previous IZA research has shown that low birthweight has long-term adverse effects on education, income, and mortality, the “children of crisis” are likely to face disadvantages later in life that warrant policymakers’ attention.