After a decade of declining rates of crime and homicides, more recently Brazil has observed a steep increase in violent crime, with more than 60,000 victims of homicides in 2018 alone. Studies have estimated that the economic cost of violence in Brazil corresponds to 5% of the country’s GDP. Yet little is known exposure to day-to-day crime may affect educational outcomes of children. Being exposed to violent crime may cause trauma to children, and the uncertainty associated with observing violent crimes may undermine incentives to invest in human capital.

Estimating the causal effect of exposure to day-to-day violence on educational outcomes, such as test scores, school attendance or dropout is complicated by the fact that the incidence of crime varies with a multitude of socioeconomic characteristics of a neighborhood. Because these characteristics are also reflected in the socioeconomic composition of students in schools in these neighborhoods, it is difficult to determine whether it is the violence level and exposure to crime or some related neighborhood characteristic that is affecting schooling outcomes. For example, neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic status often register higher crime rates while socioeconomic difficulties may in turn negatively affect schooling performance, which makes it difficult to isolate the effect of violence from other sources of disadvantages.

Crime and violence around schools

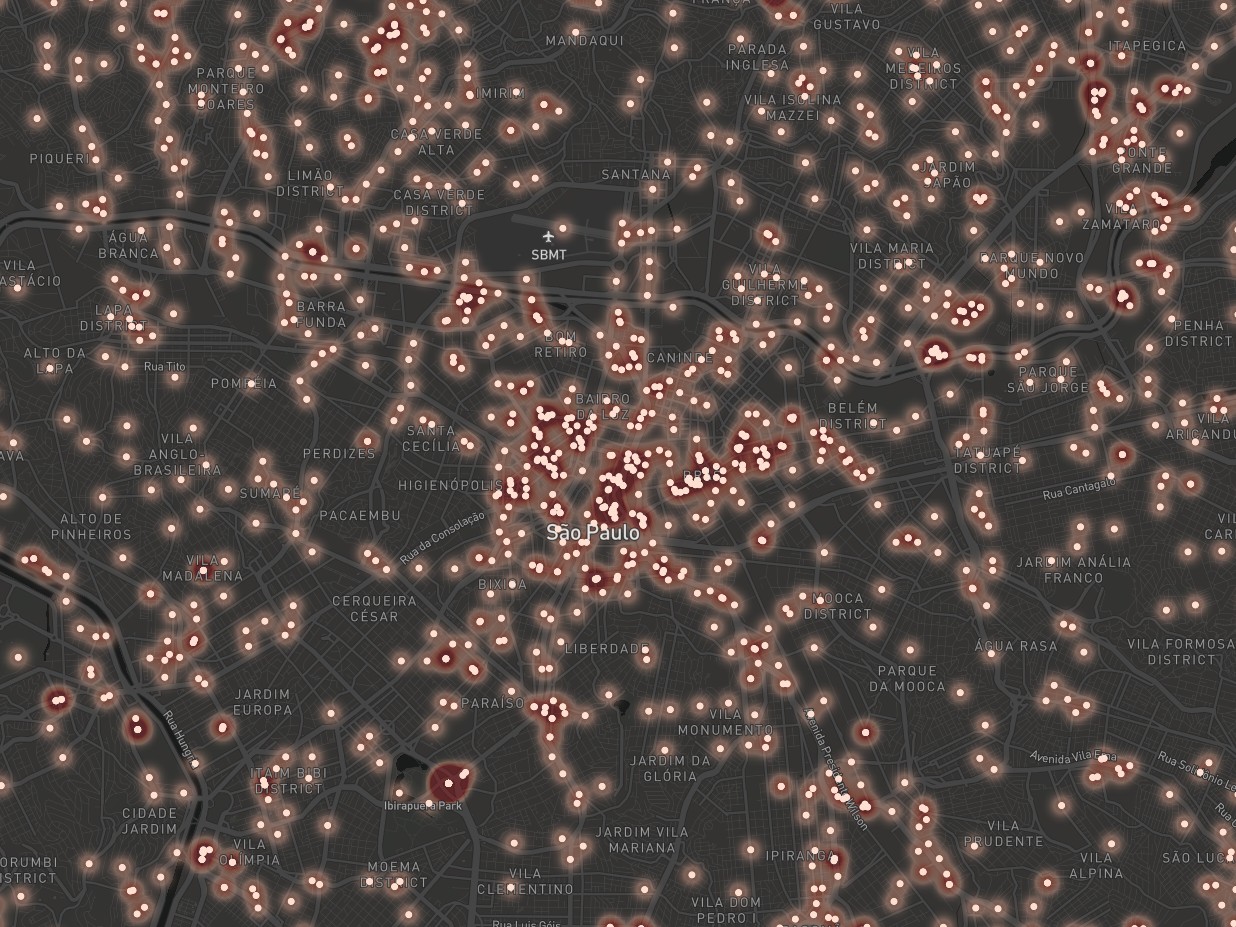

In a recent IZA discussion paper, Martin F. Koppensteiner and Lívia Menezes address this difficult empirical exercise by utilizing unusually detailed data on the exact location and timing of crimes in relation to schools and individual ways to school of more than 600,000 primary and secondary school students in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. They estimate the effect of exposure to these homicides on test scores, student and parental reported aspirations, and attitudes towards education.

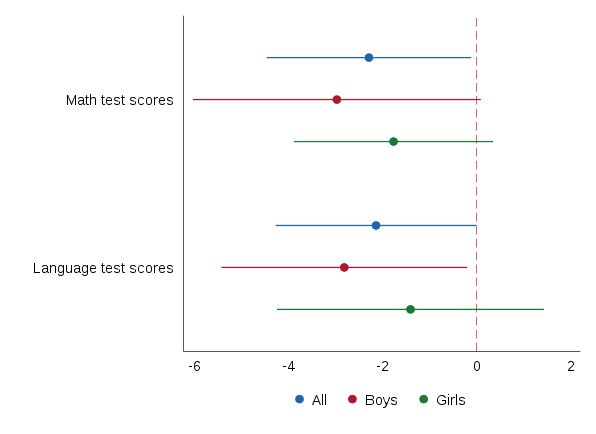

Exposure to violence around the schools leads to a substantial deterioration in the educational performance of school children. The authors estimate that one additional homicide in a 25 meters radius around schools reduces test scores in math and language by about 5% of a standard deviation in test scores. These effects are not short-lived but hold for exposure even more than six months before the test date. They also reduce attendance and increase drop-out. Figure 1 shows that the estimated effects are more pronounced for boys and this pattern is replicated across other outcomes, such as attendance.

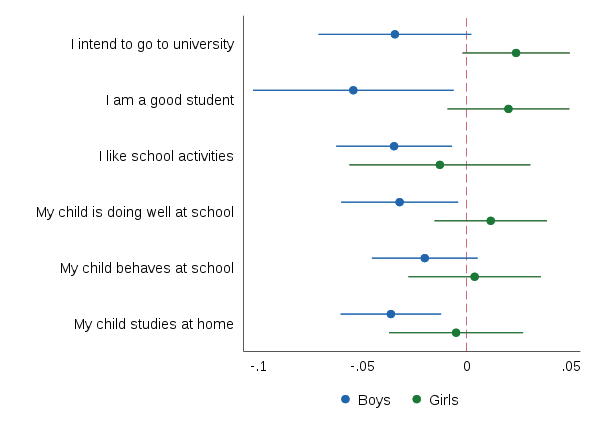

Lower aspiration towards school after exposure to violence

The study also shows that aspirations and attitudes towards education reported by students and their parents are affected by exposure to violence. Again, the effects vary by sex. For example, after exposure to violence, boys are less likely to say that they intend to go to university or that they are good students, and they are overall less interested in school activities. The effects on self-reported attitudes are confirmed by the effect on parental assessment of their children’s attitude towards education.

These results contribute to better estimates of the socioeconomic cost of crime. Exposure to violence negatively affects the educational outcomes of children and hinders their investment in human capital. Given the abundance of violent crime in Brazil, this may reduce later-life opportunities for a large number of children, especially boys.