Patience is an important trait in children that can make a difference for a lifetime. Many disciplines, including economics, have studied how patience in intertemporal choices – preferring a later but larger reward over a sooner but smaller reward – is related to health and wealth outcomes.

For instance, it has been shown that more patient adults perform better at work and stay in their job longer; they have lower credit card debt and are less likely to smoke. For teenagers, a positive relation between patience and school performance or a healthy lifestyle has also been documented. Even more impressive, long-term studies have shown that a child’s degree of patience is positively related to long-term outcomes in adulthood, such as higher education, higher income, better health status (by being less likely obese, drinking or smoking) or lower crime rates.

For instance, it has been shown that more patient adults perform better at work and stay in their job longer; they have lower credit card debt and are less likely to smoke. For teenagers, a positive relation between patience and school performance or a healthy lifestyle has also been documented. Even more impressive, long-term studies have shown that a child’s degree of patience is positively related to long-term outcomes in adulthood, such as higher education, higher income, better health status (by being less likely obese, drinking or smoking) or lower crime rates.

A recent study by Matthias Sutter (University of Cologne), Silvia Angerer (IHS Carinthia), Daniela Glätzle-Rützler (University of Innsbruck) and Philipp Lergetporer (Ifo Institute) examines whether the language that children speak is related to how patient they are in experimental choices.

Why language makes a difference for intertemporal choice

The “linguistic-savings” hypothesis introduced by Keith Chen states that languages which grammatically separate the future and the present induce less future-oriented behavior than languages in which speakers can refer to the future by using present tense. In English, one could say “it will be cold tomorrow”, but not “it is cold tomorrow”. The former example characterizes languages that are said to have strong future-time reference (s-FTR). The latter example, however, sounds fine in languages like German that are said to have weak future-time reference (w-FTR).

In English or Italian (both s-FTR), where future tense is used, the future may seem more distant when referring to future events, thus inhibiting future-oriented behavior, due to the separation of future and present in a grammatically proper use of the language. In German (w-FTR), the ability to refer to future events by using present tense may reduce the magnitude with which future events are discounted because they seem closer to the present and more certain to manifest, thus making future-oriented choices more attractive. The grammatical difference between s-FTR and w-FTR languages may thus affect economic behavior, in particular decisions with intertemporal consequences.

German-speaking kids are more patient than their Italian-speaking peers

The authors test this influence of language on intertemporal choices in a controlled and incentivized experiment in the North Italian city of Meran, which is German- and Italian-speaking in equal parts. This offers an almost ideal experimental setup. Citizens of both language groups live next-door to one another, but schools are segregated by language, despite serving children from the same neighborhoods.

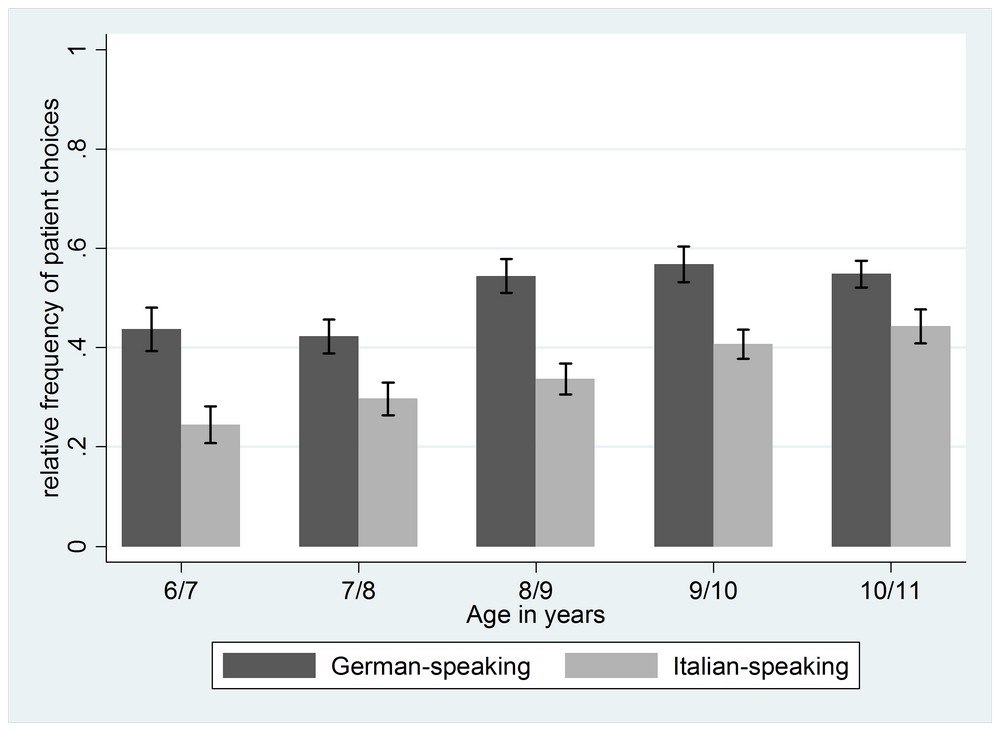

In the experiment, time preferences of 86% of all primary school kids (860 children) were measured with three simple choice problems referring to choose between few gifts today or more gifts in a few weeks. The results show that German-speaking children are significantly more patient in their choices than Italian-speaking children and are more willing to delay gratification. This general pattern persists across all age groups, indicating that already at the age of six years there is a strong difference between both groups of children (see figure below).

The authors show that these results are not related to differences in socio-demographic background data, IQ and risk attitudes. Interestingly, when parents in a household speak both languages, then the child’s level of patience in experimental choices is intermediate to the cases when both parents in the household speak only one language, either Italian or German.

The authors show that these results are not related to differences in socio-demographic background data, IQ and risk attitudes. Interestingly, when parents in a household speak both languages, then the child’s level of patience in experimental choices is intermediate to the cases when both parents in the household speak only one language, either Italian or German.

Promote future-oriented behavior: Patience can be trained

A straightforward implication of the main finding in this paper is the question how one can contain the higher degree of impatience in speakers of s-FTR languages. This is where recent work in behavioral economics can potentially offer a starting point for future studies. Setting appropriate defaults, encouraging active decision-making (by making the choice options more transparent and forcing subjects to make a choice), or providing commitment facilities have been identified as useful instruments to promote future-oriented behavior.

Given the findings on the relation between language and intertemporal choices, it is an interesting question for future research whether these instruments work equally well in languages with weak or strong future-time reference and how they could be used to train the patience of children. Given the long-term benefits of patience, answering these questions promises great benefits for individuals and society as a whole.