The COVID-19 pandemic and the fight to contain it have had widespread large effects on individual well-being, but the channels are less clear. Was the incidence and fear of infection more impactful, or the consequences of containment policies? Perhaps the pandemic, in which everyone is at risk, engendered a positive sense of solidarity. How resilient were we – were the impacts lasting? To answer these questions, a recent IZA discussion paper by Francesco Sarracino, Talita Greyling, Kelsey O’Connor, Chiara Peroni and Stephanie Rossouw describes the changes in well-being that occurred throughout 2020 in ten mostly European countries.

The authors first computed a real-time measure of well-being referred to as Gross National Happiness (GNH) using tweets as they are posted. Compared to the snapshots provided by surveys, data from Twitter reveal a much more varied picture. Tweets provide a wealth of information that can be transformed into usable data using sentiment analysis – an automated process that uses natural language processing to determine the feelings and attitudes of a written text’s author.

Sentiment analysis has been used by many researchers, for instance, to predict future events, such as the result of elections or stock markets, to track the influenza rate, and to measure people’s well-being. Using this process to derive the sentiment of each tweet, the authors calculate GNH as the average sentiment expressed in a country during a particular day. They focus on seven European countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Spain and the United Kingdom.

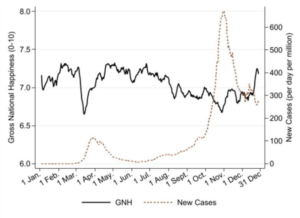

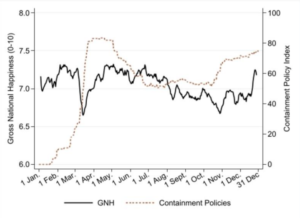

The paper finds that well-being declined dramatically at the onset of the pandemic in March 2020. The initial decline in GNH is partially explained by the exponential rise in confirmed COVID-19 cases (left figure) and severe containment policies (right figure) that were implemented in mid-March. After the initial shock, shortly before the peak of the first wave, well-being began to recover, reaching pre-pandemic levels by the end of April. In mid-year, as cases started to slowly climb again, well-being slowly declined, reaching another minimum at the end October, which corresponds with another peak in cases.

Beyond these observations, regression analysis suggests well-being declined as a result of COVID-19 cases and containment policies, and between the two, cases had a more robust negative impact throughout 2020. The regression results also show that economic fear, trust in national institutions, and loneliness were not significantly associated with GNH. This puzzling finding could indicate that health and lockdown concerns dominated individuals’ mood during the pandemic.

While GNH, like any indicator, has its limitations and may not fully capture country-specific aspects differences or long-run impacts, various tests conducted by the authors suggest that it does serve as a valid and reliable measure of well-being. A key finding from this analysis is how quickly people recovered during the first wave. Real harm was caused to mental and physical health, but people also revealed significant resilience.