Recent media coverage of air pollution in New York City resulting from wildfires in Canada has heightened awareness of the detrimental impact that drifting wildfire smoke can have on populations located far from the actual fires. In a 2022 IZA discussion paper (forthcoming in the Review of Economics and Statistics), researchers have quantified this effect, estimating the associated welfare cost of income losses attributable to exposure to air pollution.

Approximately 20 percent of the fine particulate matter emitted in the United States is caused by wildfires. The impact of ambient air pollution on human well-being has been well-documented, particularly in terms of health, such as increased hospital visits and premature mortality among children and the elderly. But air pollution exposure can also reduce adult labor supply and productivity. This can occur through health-related impacts or by causing individuals to undertake costly avoidance or defensive actions. Survey research on wildfire smoke specifically has revealed various behavioral responses, including spending more time indoors and missing work.

Challenges in measuring the causal effect

Measuring the causal effect of air pollution on nationwide labor market outcomes presents a key challenge. It requires identifying geographically widespread pollution fluctuations that are not driven by factors directly affecting economic activity. For example, the establishment of a new factory may create jobs but also worsen air quality. Simply comparing employment and air pollution before and after the factory’s construction would likely underestimate the negative effects of air pollution on labor market outcomes.

The study by Mark Borgschulte, David Molitor and Eric Zou argues that wildfire smoke traveling thousands of miles serves as exogenous variation in local air pollution, meaning it is unconnected to local economic factors such as industry and regulations. This allows them to estimate the causal effect of wildfire smoke and air pollution on income and employment.

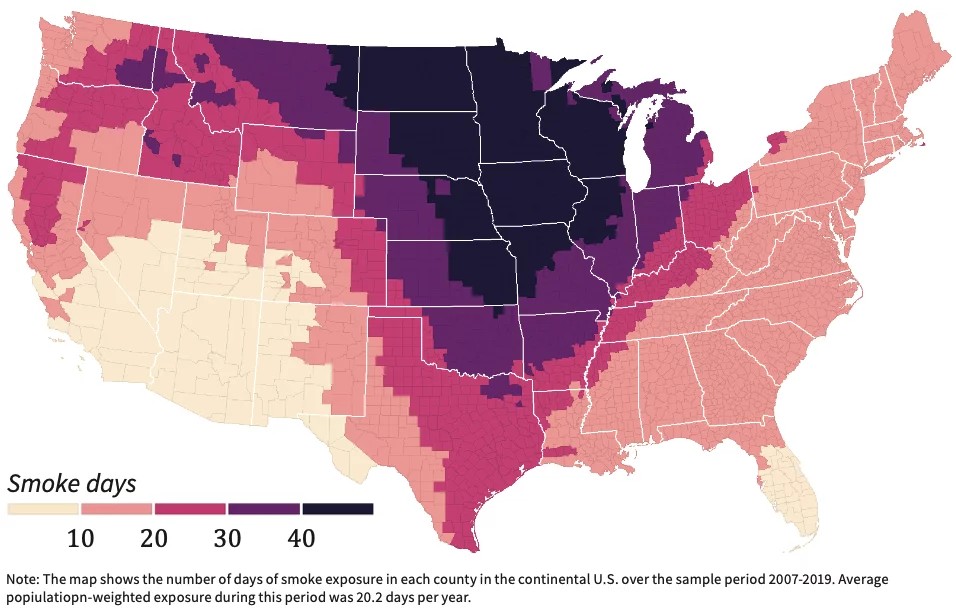

The analysis relies on three primary data sources from 2007 to 2019: high-resolution remote sensing data from satellites showing the locations of wildfire smoke plumes in the United States, air quality data from ground-level pollution monitors, and labor market data for all counties in the continental United States.

Decrease by nearly 2 percent of annual labor income

The study demonstrates that exposure to wildfire smoke leads to statistically and economically significant losses in labor income and employment. The authors estimate that each day of smoke reduces quarterly per capita earnings by $5.2, or approximately 0.10 percent. Multiplying this effect by the average number of smoke days each year, they calculate that wildfire smoke decreases earnings by nearly 2 percent of the annual U.S. labor income (equivalent to $125 billion in 2018 dollars) on average between 2007 and 2019.

The impact of smoke is more pronounced among older workers, suggesting that age and related poor health may amplify the negative labor market effects of air pollution. An additional day of smoke exposure reduces employment by 80 employees per million residents aged 16 and older, which explains 13% of the total earnings effect of smoke exposure.

The study’s examination of plausibly exogenous variation in wildfire smoke exposure provides one of the first national estimates of the causal effect of ambient air pollution exposure on labor market outcomes. The baseline estimates suggest that a 1 µg/m3 increase in quarterly ground-level fine particulate matter concentrations reduces per capita earnings in the quarter by $103 and employment by 1,750 workers per million residents aged 16 and older.

Regulation should also take labor market costs into account

Notably, the pollution variation studied in this paper primarily falls below the regulatory standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency. However, the findings indicate that such pollution may significantly reduce labor market earnings. Failure to consider labor market costs may result in inefficient pollution standards and regulations, the authors argue.

Their paper contributes to the growing body of evidence on the effects of climate change, particularly increasing heat exposure, on labor market outcomes. For instance, an earlier IZA dscussion paper demonstrated that rising temperatures in California have increased the occurrence of workplace injuries.