How does immigration of poor people affect the lives of natives? This old policy question has recently gained extra attention in countries with large immigrant and refugee inflows. One recurring concern in the public debate is that generous welfare states attract low-skilled immigrants who supposedly benefit from public spending while contributing little in taxes. Consequently, immigration may reduce the level of taxation and spending if it lowers native voters’ support for redistributive policies – possibly also at the expense of poor natives.

However, this relationship may change if immigrants are allowed to vote as well. A recent IZA discussion paper by Arnaud Chevalier, Benjamin Elsner, Andreas Lichter and Nico Pestel analyzes how immigration causally affects redistribution in a setting where immigrants are granted immediate voting rights. Exploiting a historical episode of mass migration to post-war West Germany as a natural experiment, the paper provides evidence that the inflow of poor immigrant voters led to a more generous welfare state and had a lasting impact on preferences for redistribution.

Voting rights and welfare eligibility

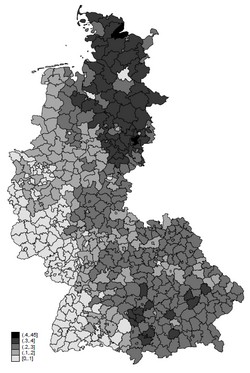

After the end of World War II, twelve million Germans were forcibly displaced from the territories ceded to Poland and the Soviet Union. Around two-thirds of them settled in West Germany, which increased the West German population by almost 20% within a very short period of time, with the migrant population share varying by county from below 2% to more than 40%. These migrants were considerably poorer than the average native. However, as German citizens, they had voting rights and were eligible for social welfare from their time of arrival.

After the end of World War II, twelve million Germans were forcibly displaced from the territories ceded to Poland and the Soviet Union. Around two-thirds of them settled in West Germany, which increased the West German population by almost 20% within a very short period of time, with the migrant population share varying by county from below 2% to more than 40%. These migrants were considerably poorer than the average native. However, as German citizens, they had voting rights and were eligible for social welfare from their time of arrival.

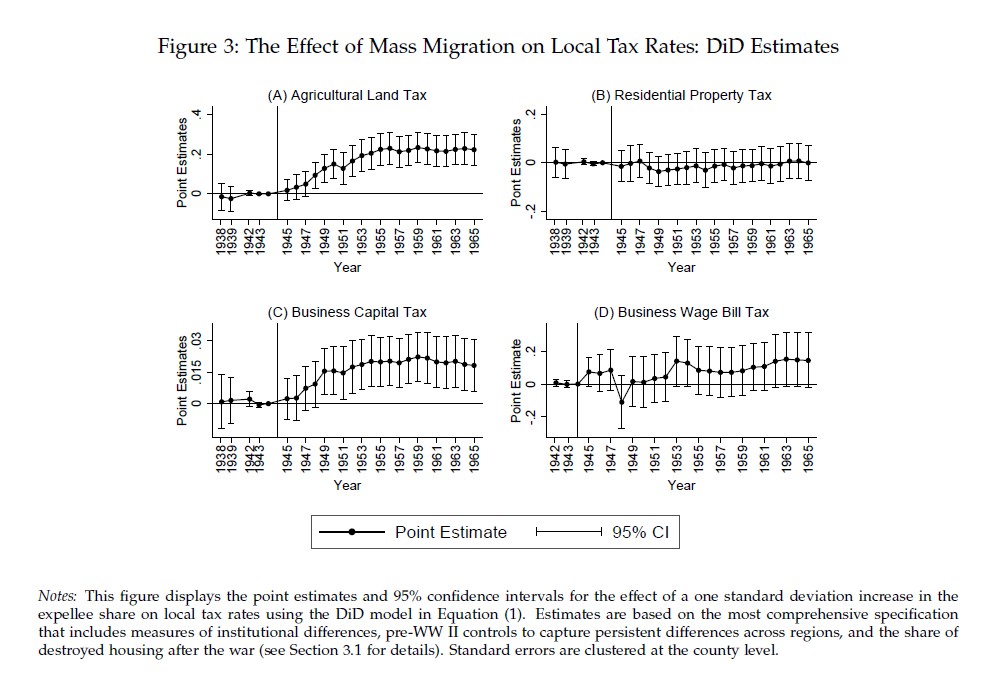

Using panel data for West German cities, the study finds that local governments responded to the migration shock with selective and persistent raises in local taxes as well as shifts in municipal spending. Farm and business owners were taxed more while residential property and wage bill taxes remained largely unchanged (see figure below). High-inflow cities significantly raised welfare spending while reducing spending on infrastructure and housing.

Long-lasting effects

Election data suggest that these policy changes were partly driven by the political influence of the immigrants. In high-inflow regions, the major parties were more likely to nominate immigrants as candidates, and a pro-immigrant party received high vote shares. The impact of the expellees can be felt until today: More than 50 years later, people living in areas with larger inflows in the 1940s still have a substantially higher demand for redistribution.

The findings have implications for today’s debates about migrants’ voting rights. For example, intra-EU migrants are currently allowed to vote in local elections in their country of residence. But the largest global migration flows still occur within countries, especially from rural to urban areas. The study suggests that larger cities with a growing population of poor migrants may see a shift of the political landscape if the migrants have the same voting rights as the incumbent population.