Cities are home to more than half the population of developing countries. Many cities struggle to deal with large-scale urban violence, crime, and drugs, especially among poor young men. In post-conflict and fragile states, poor young men are also targets for mobilization into election intimidation, rioting, and rebellion.

Cities are home to more than half the population of developing countries. Many cities struggle to deal with large-scale urban violence, crime, and drugs, especially among poor young men. In post-conflict and fragile states, poor young men are also targets for mobilization into election intimidation, rioting, and rebellion.

In Liberia, which saw two civil wars between 1989 and 2003, development experts and policymakers are seeking evidence on the most effective ways to reduce crime and violence among high-risk young men. Two of the most common policy prescriptions—job creation and policing—aim to reduce crime and violence by either changing the incentives facing young men or punishing them.

An alternative approach seeks to rehabilitate high-risk men, using therapy and counseling to foster “character skills” such as self-control and a noncriminal self-image. It has been unclear, however, whether character and self-image are malleable in adults, especially “hard core” criminals or drug users.

Researchers from Columbia University, Harvard Medical School, and the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau partnered with Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) to test and evaluate innovative approaches for reducing crime and violence in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia. They recruited the highest risk men—those engaged in regular crime, drugs, and violence.

The study was conducted within the GLM|LIC program funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and coordinated by IZA.

The study was conducted within the GLM|LIC program funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and coordinated by IZA.

The main program, the Sustainable Transformation of Youth in Liberia (STYL), was an 8-week program of cognitive behavior therapy developed by a local community organization. The therapy, led by reformed street youth and ex-combatants, aimed to foster self-control and a new self-image as a member of the community. The study also tested unconditional cash transfers to the high-risk men, with and without therapy.

The evaluation found that even these highest-risk young men largely invested and saved the unconditional cash transfer. Almost none was spent on drugs, alcohol, or other temptations. Yet the money only produced short-run improvements in investment and income.

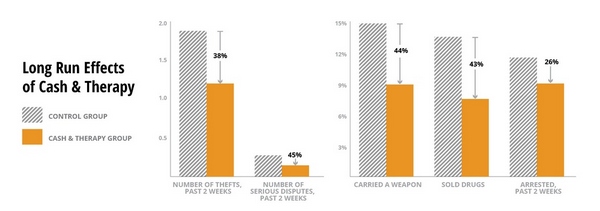

The therapy program, however, while not affecting income, led to persistent falls in crime, drug use, and violence—especially in the group receiving cash in addition to therapy. Researchers concluded that self-control and self-image are malleable, and that cognitive behavior therapy can help reduce less organized, impulsive, and expressive forms of violence and crime.