IZA World of Labor, the unique online resource for evidence-based policymaking, has now published over 200 articles! The author of the most recent article, Michael A. Clemens (Center for Global Development and IZA), is one of the leading scholars in the economics of migration. During his visit to IZA last week, we took the opportunity to talk to him about what constitutes smart policy toward high-skill emigrants.

IZA: With the refugee crisis dominating European headlines, public opinion is starting to turn against legal immigration driven by economic motives. More and more people support politicians who advocate more restrictive immigration policies. What is your opinion, based on the evidence?

Clemens: The effects of refugees and economic migrants are created primarily by policy. It is possible to turn either refugees or economic migrants into a burden. It is also possible to turn them into a resource. This is a choice. There is recent and groundbreaking research on this, in two very different settings. Low-skill refugees in Denmark have raised the wages of native Danish workers. This is shown in a study with data on every single worker in Denmark across two decades, by Mette Foged of the University of Copenhagen and Giovanni Peri of the University of California Davis. When refugees were dispersed across the country, they generally complemented the labor of native workers. And where they did displace limited numbers of native workers, those natives ended up earning more, because they were displaced into jobs requiring more complex tasks.

The result is similar in a radically different setting: the effects of the two million Syrian refugees now in Turkey. You might think that such a large and unmanaged flow, unlike in Denmark, would have to break the Turkish labor market. But that refugee inflow, too, has actually raised wages for Turkish workers. This is shown in a remarkable new study by Ximena del Carpio of the World Bank and Mathis Wagner of Boston College. Those refugees have displaced many Turkish workers, but they have displaced many of them into higher-paid formal work, while Syrians take the informal jobs that Turks used to fill.

It didn’t have to work out this way. In either of these situations, policy could have converted these people from an economic resource into an economic burden. Denmark, instead of spreading refugees around the country and helping integrate them into the labor force, could have tried to ‘protect’ native workers from them (as some Eastern European countries are doing now). This, Foged and Peri show, would have actually harmed native workers. Turkey, rather than issuing Syrians identification cards designed to facilitate job offers, could have confined them in the camps and actively prevented them from working (as Lebanon has done). That would have lowered Turkish wages and increased their dependence on government handouts. In economic terms, there is nothing necessarily beneficial or harmful about people arriving in desperate conditions; policy makes the difference.

IZA: Many have advocated limits on high-skill migration in the name of economic development overseas, to keep skilled people from leaving countries where they are needed. In your IZA WoL article, you argue that many such policies are misguided. How is that?

Clemens: This is a common idea. Even respected development experts have recommended blocking migration of skilled people from poor countries on these grounds. The basic problems with such policies related to effectiveness and ethics.

On effectiveness: They have never been shown to work. Think about a poor neighborhood you are familiar with, and consider whether forcibly preventing smart young people from leaving that neighborhood would result in improved well-being there. For one thing, you might find the brightest kids being a lot less interested in school if they knew that they could never work outside a ghetto, where their efforts would be rewarded. There would be many other pernicious effects as well. With countries, too, there are indirect effects of this kind. This is why no one has ever demonstrated a positive effect on development, economic or otherwise, from trapping skilled people inside a poor country. In fact, if you think of places where skilled people really have been trapped against their will in the past—East Germany, North Korea—you are not thinking of places with vibrant development.

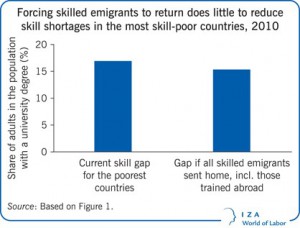

Beyond this, for the truly poor countries the problem is that they have extremely few skilled workers, period, not that those skilled workers are leaving. Think of the countries on earth with the lowest numbers of university-educated workers as a fraction of the labor force, like Malawi. Even if some draconian policy somehow forced all the skilled people from those countries who are abroad to return home—including the ones who got their training abroad—this would barely change the skill shortages at home.

Beyond this, for the truly poor countries the problem is that they have extremely few skilled workers, period, not that those skilled workers are leaving. Think of the countries on earth with the lowest numbers of university-educated workers as a fraction of the labor force, like Malawi. Even if some draconian policy somehow forced all the skilled people from those countries who are abroad to return home—including the ones who got their training abroad—this would barely change the skill shortages at home.

And on ethics: Think for a moment about the policy I just mentioned, of forcing all skilled people from poor countries to go back there. That prospect should be shocking and abhorrent. Imagine someone arriving at your own door, and informing you that your plans for your life are not important, and that someone else has determined that your skills are needed in a place you have decided you don’t want to live—so you’ll be sent there against your will. It would shatter your universe; it is not something we should discuss casually. The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 13, guarantees the unconditional right of all people to leave any country they wish to leave, for any reason. Interfering with such a basic human right is something we should only ponder gravely, in the face of extremely compelling evidence that it would do good. As I mentioned above, we don’t have such evidence.

IZA: But why should politicians in developed countries care? And what can they do?

Clemens: Politicians who care about development should promote well-regulated skilled migration. High-skill emigration brings many indirect benefits to developing countries. Economists have shown that high-skill emigration increases trade for the countries that those migrants leave, by building their networks abroad. And it increases not just the amount of trade, but the diversity of products produced and exported. High-skill migration similarly causes investment in the countries migrants come from, and transfers new technologies (measured by patents) to the countries of origin. The effects of skilled workers are global, and many of them do more for their countries abroad than they can do at home.

These effects are documented in rigorous statistical studies. But they are easy to see as well. A well-known example of this is Mohamed Ibrahim, an engineer who once worked as a functionary in Sudan’s telecommunications agency. He emigrated to the United Kingdom and founded a telecom company, later bringing new technologies and billions in investment to Africa. A shortsighted policymaker may have tried to block him from leaving Sudan in the first place, since his ‘skills were needed’ there. Farsighted policymakers understand that the world and the economy are much more complex than that.

But this does not mean that regulation on skilled migration, in the name of development, is useless. An important concern for the countries that skilled migrants leave is a fiscal concern: many poor countries heavily subsidize higher education, and this can turn skilled emigration into a fiscal drain. The best policy solution to this isn’t to block skilled migration, which is ethically problematic and would cut off the many benefits. Rather, a policy priority is to develop systems of higher education finance that are built around the reality of migration, encouraging skill formation and mobility while limiting fiscal drain. I proposed one such system in IZA’s Journal of Labor Policy, but we need a lot more innovation here.