Trends of globalization such as migration, economic integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.

integration and digital communication are undoubtedly bringing people closer together. But do they also cause the levels of satisfaction to converge? Researchers have long studied the institutional factors contributing to the strong international differences in life satisfaction.

The transition of the Central and Eastern European states after the collapse of the Soviet Union provides a particularly rewarding object of investigation in this respect. It entailed a series of socioeconomic, political and institutional transitions in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the former Soviet Union (FSU). Unemployment, inequality, income volatility, and, in some cases, civil war accompanied the more positive experiences of obtaining new political rights and civil liberties.

In addition to far-reaching economic reforms to establish market economies, these transition countries had to create the legal and institutional foundations that underpin modern democratic and capitalist nations. This involved fundamentally reforming old institutions or creating new modern institutions of public finance, central banking, and customs.

Life and unhappiness in transition

Many papers have tried to uncover the factors behind the declining life satisfaction levels during the transition and have concluded that rising unemployment, inequality and uncertainty, income volatility, rapidly changing social norms, and declining social protection are some viable explanations (see for example IZA DP 3409 and this 2009 article about the (un)happiness in transition).

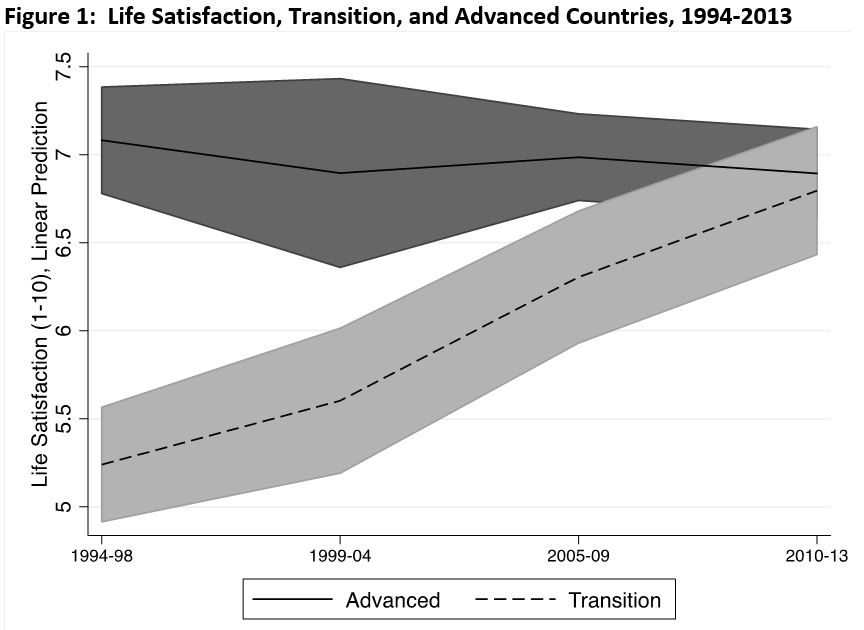

However, despite their dramatic declines in the early 1990s, income and consumption improved substantially by the late 1990s, suggesting that the transition was a successful process. Yet, alongside these improvements, subjective well-being indicators show a more nuanced story. During the 1990s, mirroring the income trends, life satisfaction in transition countries sharply declined, and while it started to recover in the 1990s, it failed to match the recovery in GDP.

What can close the life satisfaction gap?

Despite the large literature that examines the transitioning process, few studies look at the life satisfaction differentials between transition and non-transition economies. In a new IZA Discussion Paper, Milena Nikolova studies the life satisfaction gap between post-socialist and advanced Western societies and the role of the rule of law in explaining this gap.

As the transition process entails reaching the quality of life levels in developed countries, advanced countries are the relevant comparison group. Because the rule of law is related to democratic institutions and the market economy, it is particularly relevant for transition economies, where such reforms were most pronounced in the 1990s.

Using World Values Survey data for 1994-2013, Nikolova shows that the average life satisfaction between advanced and transition countries has started to converge in recent years. In a regression framework, she demonstrates that the life satisfaction differential persisted until the early 2000s but had closed during the 2010-2013 period (see figure).

(Source: IZA DP No. 9484)

Combining her analyses with macro-economic data from the World Development Indicators and institutional data from the International Country Risk Guide, the paper further demonstrates that macroeconomic factors (GDP per capita, inflation, and unemployment) explained part of the life satisfaction gap reduction.

The rule of law, which refers to a system of well-defined, universally applicable, and fair laws, was an additional factor reducing the size of the life satisfaction gap in the early 1990s, and it completely explained the gap by the late 1990s. In fact, it appears that holding both macroeconomic factors and the rule of law constant, respondents in transition countries appear to be 0.6 points more life satisfied than those in advanced countries in the 2010-2013 survey wave (on a 1-10 scale). This result may be due to the differential timing and effects of the financial crisis—i.e., the economic crisis appeared in Eastern Europe later than in the West and abated by 2010.

Nikolova’s findings suggest that the completion of the transition process may be in sight, at least in the minds of ordinary people in post-socialist countries. As institutions and macroeconomic conditions continue to improve, post-socialist countries may achieve objective and subjective quality of life levels similar to those in the West.