Depression, which is the focus of this year’s World Health Day, is also an important topic for labor economists as mental health and employment outcomes are inherently  intertwined. People with poor mental health have lower levels of economic activity, lower earnings, and less stable employment. On the other hand, employment difficulties can undermine mental health; many who struggle to find meaningful work or who lose their jobs will experience poorer mental well-being as a result.

intertwined. People with poor mental health have lower levels of economic activity, lower earnings, and less stable employment. On the other hand, employment difficulties can undermine mental health; many who struggle to find meaningful work or who lose their jobs will experience poorer mental well-being as a result.

Mental health issues: cause or consequence of poor labor market outcomes?

A new IZA Discussion Paper by Melisa Bubonya, Deborah A. Cobb-Clark and David Ribar uses nationally representative data to estimate how transitions into and out of depressive episodes affect subsequent employment outcomes, including participation, employment and unemployment. Further, the authors address the potential for the reverse relationship to exist by estimating how changes in employment status affect the chances developing severe depressive symptoms. Their aim is to shed light on the interplay between depression and the labor market, which is particularly important because the appropriate policy responses depend on whether depressive issues are a consequence or a determinant of poor labor market outcomes.

Men’s mental health more closely tied to employment outcomes

The findings show that severe depressive symptoms lead to economic inactivity by reducing labor force participation and employment, and increasing the likelihood of unemployment. Severe depressive symptoms are also partially a consequence of economic inactivity. Interestingly, the results show larger effects for men than women, indicating that men’s mental health is more closely tied to their employment outcomes than is women’s. Further, men seem to be more responsive to the shock of a bad event — either the onset of a depressive episode or the onset of unemployment. In contrast, women appear to be more affected by prolonged depressive symptoms.

The results imply that reducing the economic costs of mental illness is a challenge that is best tackled from both sides: improving mental health by promoting economic activity, minimizing employment disruptions and shortening unemployment spells, and reducing the barriers to employment and providing positive work environments for those with mental health issues. The results also call for a gendered approach to these policies.

The economics of mental health

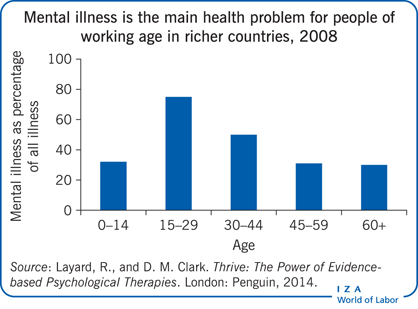

A recent IZA World of Labor article by Richard Layard stresses that mental illness accounts for half of all illness up to age 45 in rich countries, making it the most prevalent disease among working-age people (see figure). Since mental illness costs billions in welfare payments and lost taxes, Layard argues that better treatment would more than pay for itself.

Download more IZA Discussion Papers on the topic

- Personality and Mental Health: Teenagers with low emotional stability and low conscientiousness are more likely to experience mental health problems as adults.

- Youth Depression and Future Criminal Behavior: Mental illness during childhood is related to a higher probability of engaging in criminal behavior later in life.

- Getting Stuck in the Blues: Depression proneness tends to persist. One of the risk factors is low income, which might cause individuals to get trapped in a vicious cycle.

- First Depressed, Then Discriminated Against? Revealing former depression as a reason for unemployment is rewarded by female (but not by male) recruiters. Discrimination is more pronounced in low-skill occupations.

- Religion and Depression in Adolescence: Religiosity can reduce depression as it buffers against stressors, possibly through improved social and psychological resources.

- Does Money Relieve Depression? Social pension eligibility in China has a similar impact on mental health than a medium size lottery win in Britain.