More than 75 countries have enacted legislation prohibiting workplace sexual harassment as a violation of human rights. Still, it remains a pervasive – and blatantly underreported – phenomenon that lowers workplace productivity and job satisfaction, thereby increasing absenteeism and quits.

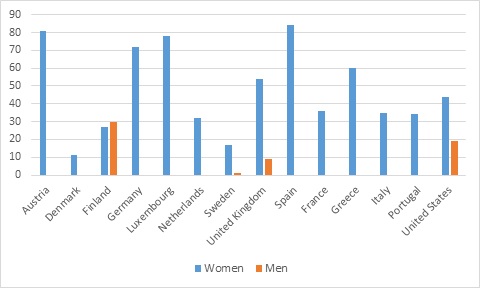

In a recent IZA World of Labor article, Joni Hersch of Vanderbilt University surveys and compares the available international evidence. She finds that sexual harassment is much more common than one might think: On average 30 to 50 percent of women have experienced sexual harassment, with rates ranging from 11 percent in Denmark to 81 percent in Australia. These striking differences, however, are not entirely due to cultural differences as survey methods differ by country.

Although men experience sexual harassment as well (on average about 10 percent in countries where this has been measured), the typical victims are young females holding a lower-rank job in a male-dominated environment. The harassers, on the other hand, are predominantly males who work at the same or higher hierarchical level. Organizational characteristics play a role as well, especially when it comes to large power differentials in the hierarchical structure and the organization’s tolerance for sexual harassment.

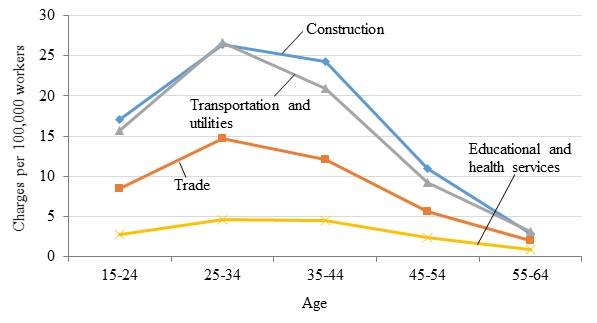

Tolerance seems to vary by industry. The construction industry, transportation and utilities are especially prone to sexual harassment in terms of charges filed. Yet, this evidence might grossly understate the problem since, for instance, 90 percent of US government workers who had experienced sexually harassing behaviors did not take formal action, possibly fearing retaliation and a worse working situation subsequently.

Costs of sexual harassment are likely to be severe and occur in form of lower job satisfaction, worse psychological and physical health, higher absenteeism, less commitment to the organizations, and a higher likelihood of quitting one’s job. For the US, estimated costs of sexual harassment over a period of two years accounted for about $327 million. A second source estimated an individual cost of $22,500 per person affected by sexual harassment, both numbers primarily driven by reduced productivity.

What can be done from a policy perspective?

Although empirical evidence on the efficacy of workplace policies in reducing sexual harassment is limited, there is a consensus that emphasizing prevention, issuing strong policy statements of no tolerance, and providing a safe mechanism for complaints of sexual harassment can be considered best practices. Trainings for appropriate behavior might also help since workers who become more aware of what behaviors constitute sexual harassment may be motivated to avoid such behaviors as well as to enforce that norm in their workgroup.

However, one should be careful not to define sexual harassment too broadly to include behavior intended as collegial or friendly, potentially creating an atmosphere of distrust and ambiguity as feared by many male co-workers in the US. Also, not all countries worldwide have legally acknowledged sexual harassment to begin with. Especially many countries in the Middle East, but also Japan, currently do not possess a law that makes sexual harassment an illegal practice.