Concerns about the health burden of obesity have prompted governments across the world to introduce sugar taxes. In March 2016, the UK Government announced a national Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) which was enacted in April 2018. The levy was particularly steep, requiring the manufacturers of sugar sweetened beverages (SSBs) to typically pay £0.24 per litre of beverage.

The goal was to substantially raise prices and thus trigger a demand response by prompting consumers to reduce their purchases of fizzy beverages. At the same time, the SDIL contained a provision to trigger a supply response: Brands that reduced their sugar content below 5g/100ml would not be levied. In a recent IZA paper, Alex Dickson, Markus Gehrsitz, Jonathan Kemp went to the data to assess the effectiveness of the levy in reducing calorie intake.

All but a few brands cut their sugar content

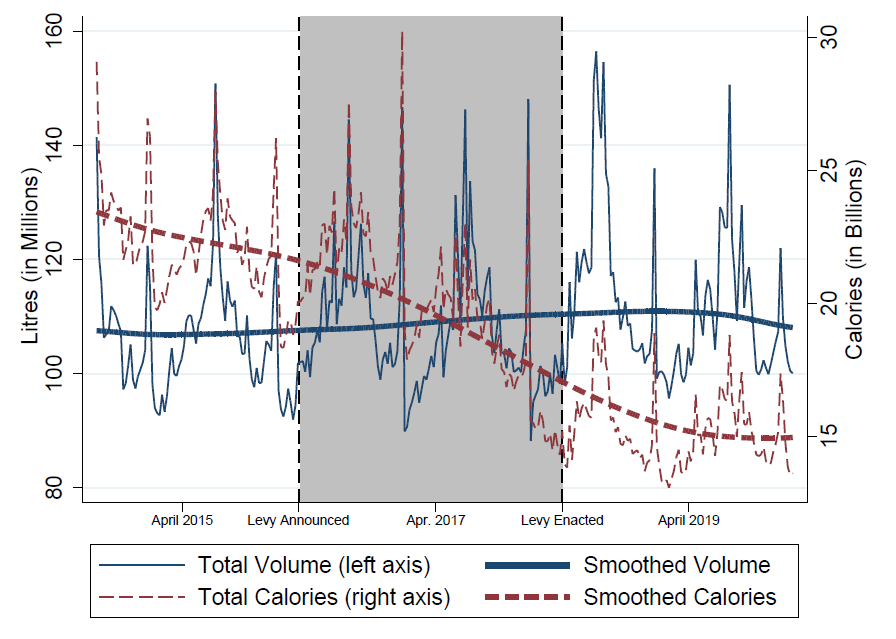

Their empirical results suggest that the levy led to massive reductions in the calorie intake and that, remarkably, most of these reductions were realized before the levy even went into effect. That is because many manufacturers used the two-year gap between levy announcement and enactment to change the recipes of their beverages. By substituting artificial sweetener for sugar, they cut their sugar content below the 5g/100ml threshold, thus avoiding the levy.

Among the 100 main brands and brand variants, which account for 73% of consumer spending in UK mainstream retailers, product reformulation was responsible for a reduction in calorie intake of about 5 billion per week. Consumers seem to barely have noticed the product reformulations as prices and volume sales held steady both before and after the enactment of the levy.

Figure 1: Aggregate weekly consumption for main UK soft drinks brands by volume (in millions of litres) and calories (in billions)

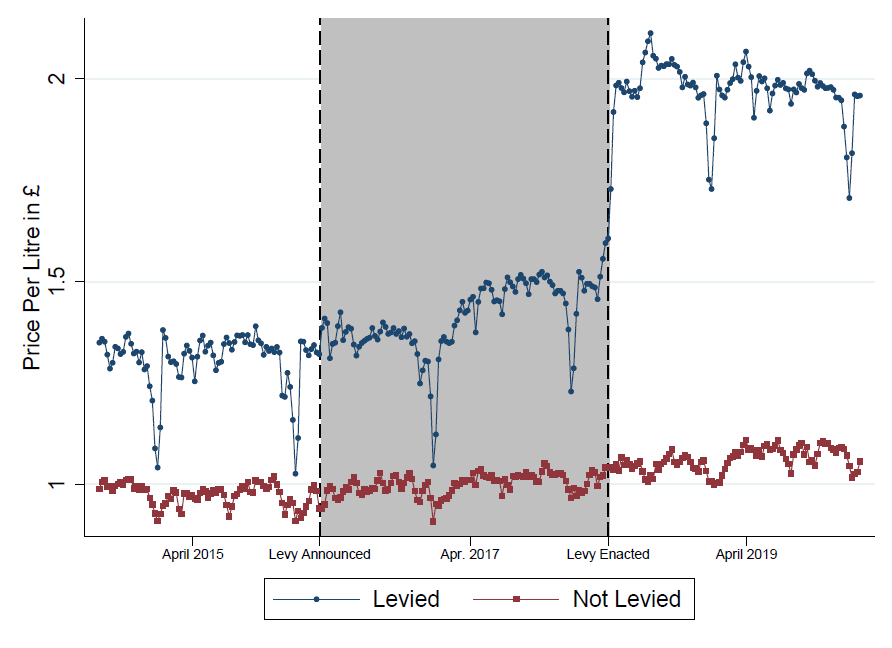

Brands that passed on the levy to the consumer paid a price for it

But not everyone changed their recipe. In particular, in the cola and energy drink segments of the market, full-sugar variants continued to feature prominently at the time the levy was implemented in April 2018. As the levy was passed on to consumers, prices shot up. In particular for colas, the price paid by consumers increased by more than the nominal tax and was over-shifted.

Figure 2: Pricing of levied and non-levied soft drinks

The consumer response followed quickly and took the form of about an 18% reduction in volume sales of levied brands. The sales response was most pronounced for large “take-home” containers of colas whereas, “on-the-go” purchases of energy drinks barely budged. At the same time sales of zero sugar diet versions increased, letting total soft drinks volumes continue its growth path. In total, levy-induced price increases and the subsequent substitution behavior took another 1 billion calories per week out of UK consumers’ diet.

Supply-side response trumps demand-side response

The authors conclude that the UK SDIL holds important lessons for policy makers. While the demand-response to higher prices is non-negligible, it is dwarfed by calorie reductions by way of manufacturers’ decision to cut the sugar content in their beverages. More than 80 percent of overall levy-induced calorie reductions were due to reformulation. As such, a tiered sugar levy that allows sufficient time between announcement and implementation, and sets a feasible target sugar level below which it can be entirely avoided through reformulation, will act as a massive accelerator.

Sugar intake from SSBs had been falling even before the levy was announced, mainly because changing consumer sentiment. Primarily because of reformulation incentives, the authors estimate that the levy sped up this process and ultimately led to an additional reduction of 6,500 calories from soft drinks per year per UK resident.