Teacher markets, like most public sector labor markets, are often characterized by a large bureaucracy and lack of flexibility. Teacher pay typically follows schedules tied to tenure and does not reward teaching performance. What happens when such heavily regulated labor markets for teachers are deregulated? A recent IZA discussion paper by Simon Burgess, Ellen Greaves, and Richard J. Murphy uses a dramatic policy change in England to examine how deregulation affected teacher pay and whether it had effects on student performance.

In September 2013, the UK Coalition Government ended the use of tenure-tied pay scales in all schools in England and required state-funded schools to introduce Performance Related Pay (PRP) schemes. In doing so, the reform completely changed the basis for setting pay, affecting the whole labor market of close to half a million teachers in the public sector, while not changing the way schools were financed.

The authors use the reform to address three key questions. First, how do schools change pay when given the freedom to do so? Second, how do these decisions affect the number of teachers employed? Finally, and possibly most importantly, does the decentralization of pay affect student performance?

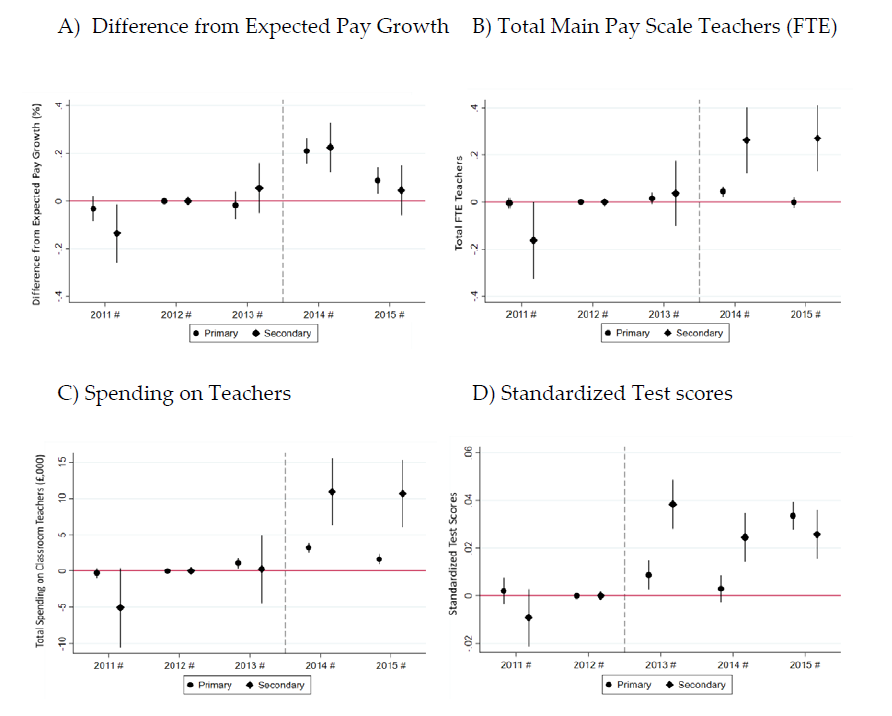

Analyzing data on all the teachers in state schools in England since 2010, the researchers computed the counterfactual expected wage growth, i.e., what teachers would have earned under the old scale point system if the reform had not been introduced.

Based on the difference between this counterfactual and the post-reform actual wage growth, the authors find that schools used their new flexibility to respond to local labor market conditions. Accordingly, teachers’ salaries grew relatively faster in high-wage labor markets (Panel A). Further, freed from the constraints of the pay scales, some schools were able to offer relatively higher salaries and to become more attractive as a place to work (Panel B).

These schools in high-wage areas attracted relatively more teachers than those in low-wage areas. Finally, the authors find that schools in high wage areas also experienced larger gains in student test scores (Panel D), especially for disadvantaged students

The results have important policy implications. National pay scales (despite their undisputed benefits of providing certainty to teachers and preventing favoritism or discrimination) might prevent local managers from allocating resources efficiently. Given autonomy, schools in high wage areas depart from the salaries determined by the national pay scales in order to increase pay and pay dispersion. This helps them retain experienced staff and ultimately improve student performance.