By Brigitte Hochmuth, Britta Kohlbrecher, Christian Merkl and Hermann Gartner

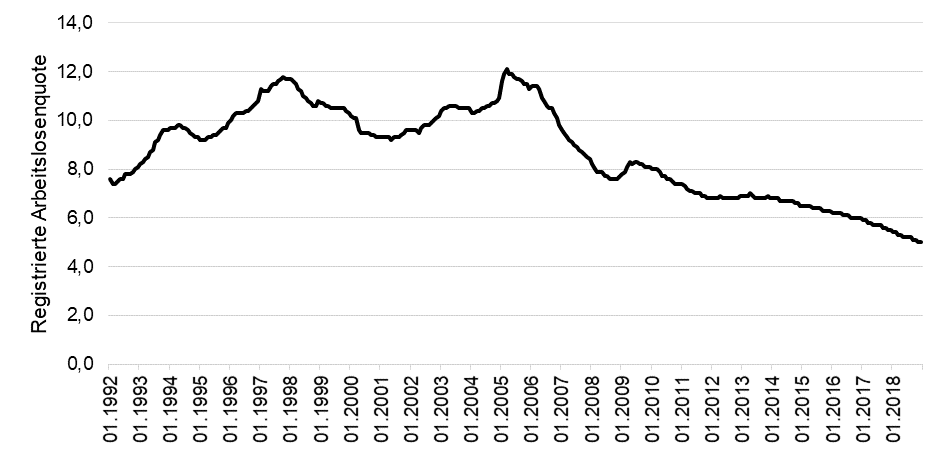

About 15 years ago, Germany implemented the Hartz labor market reforms. Since then German unemployment has dropped substantially (see Figure 1). The most controversial reform step was the so-called “Hartz IV” reform that reduced unemployment benefits for long-term unemployed. While macroeconomists agree that Hartz IV has reduced unemployment, there is no agreement by how much.

In order to quantify the macroeconomic effects of Hartz IV, it is necessary to use model-based simulations. Launov and Wälde (2013), Krebs and Scheffel (2013) and Krause and Uhlig (2012) analyze the effects of the reform on unemployment to employment transitions. However, they come up with very different quantitative results. While according to Launov and Wälde unemployment dropped by 0.1 percentage points due to Hartz IV, Krause and Uhlig find a 2.8 percentage point decline. A key reason for these differences is that each of these studies uses a different decline of the replacement rate for long-term unemployed as model input. The actual decline is difficult to measure due to complex institutional structures.

We avoid this problem by using a novel approach to evaluate the reform. We propose a macroeconomic model in which we distinguish between partial effect and equilibrium effect. We define the partial effect as the direct impact of the reform observed at the individual worker-firm level. Due to the reform, workers are ready to make concessions, e.g. accept lower wages. Thereby, firms are more likely to hire a given job applicant. In our terminology, firms’ selection rate increases.

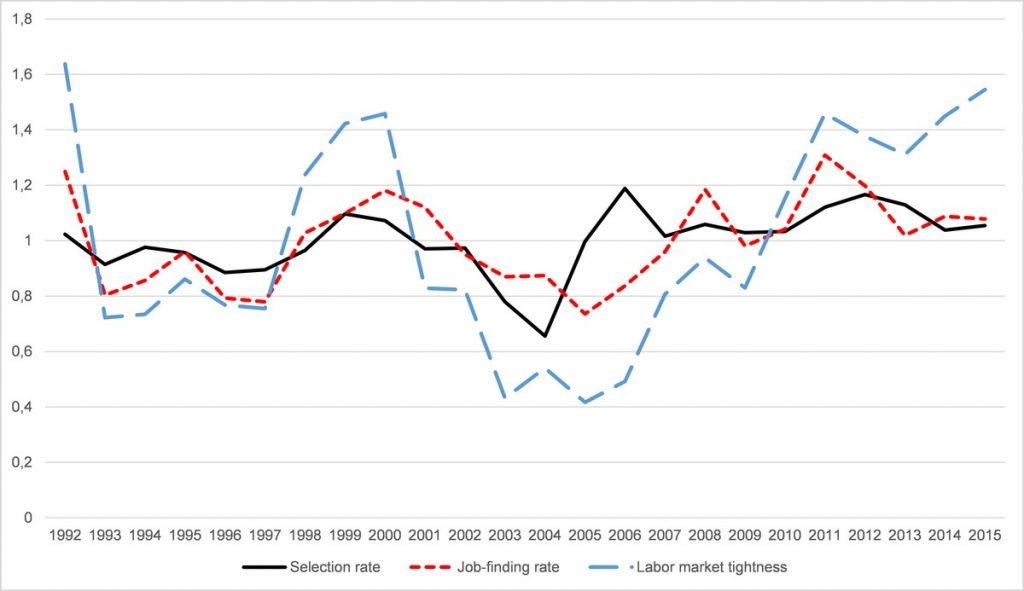

We measure the selection rate with data from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey. This measure corresponds to the share of suitable applicants hired by plants. Thus, we construct an empirical time series for hiring standards and show that this margin moves procyclically (as predicted by our model). Furthermore, we estimate the partial effect of the Hartz IV reform based on the response of the selection rate and target this effect in our quantitative model. This approach has three advantages: First, in contrast to the job-finding rate (matches over unemployment), the selection rate does not have a structural break in 2005. Second, the selection rate is not contaminated by direct effect of the Hartz III reform. Third, we measure the partial effect directly instead of assuming a certain decline of the replacement rate.

Figure 2 shows that the selection rate increases in booms and decreases in recessions. Market tightness (vacancies divided by unemployment) indicates the state of the business cycle on the labor market. Furthermore, the selection rate increased substantially at the time of the Hartz IV reform. We estimate changes of the selection rate at different aggregation levels and control for business cycle effects. Overall, according to our approach, the partial effect (i.e. increase of the selection rate) led to a decline of unemployment by about one percentage point.

However, the partial effects tells only part of the story. On top of it, there is an equilibrium effect. When unemployed workers are willing to accept a lower wage, firms start posting additional vacancies. More vacancies increase the probability of workers to get in contact with a firm. At the same time, the selection rate increases (partial effect) and thereby the probability that a contact becomes a match. Based on the observed dynamics of the job-finding rate and the selection rate, we determine the relative importance of partial effect and equilibrium effect. It turns out that both effects are similarly important. According to our model simulation, unemployment declined by more than 2 percentage points due to Hartz IV, which corresponds to around one million additional jobs.

Our results regarding the partial effect are in line Price (2018) who uses a causal microeconometric estimation at the worker level. Furthermore, our model simulation can replicate the shift of the Beveridge Curve (joint movement of unemployment and vacancies) in the aftermath of the Hartz IV reform. It has to be noted that our approach delivers a lower bound for the macroeconomic effects of Hartz IV because the reform may also have reduced separations, which we keep constant in our simulation (see Klinger and Weber (2016) and Hartung, Jung and Kuhn (2018)).

Overall, we find substantial effects of the Hartz IV reform on aggregate unemployment. According to our analysis, the reform has created at least one million additional jobs. Our paper only analyzes the positive dimension, which is an important prerequisite for a better understanding of normative aspects.