Names are often one of the first things we learn about people. They can influence our first impression and how we process subsequent information about them. Names can also serve as the basis for discriminatory behavior. For example, research shows that resumes with distinctively Black names receive 50% fewer callbacks from employers compared to identical resumes with distinctly white names. In a new IZA discussion paper, Martin Abel and Rulof Burger aim to unpack underlying reasons contributing to name-based discrimination.

What do people associate with names?

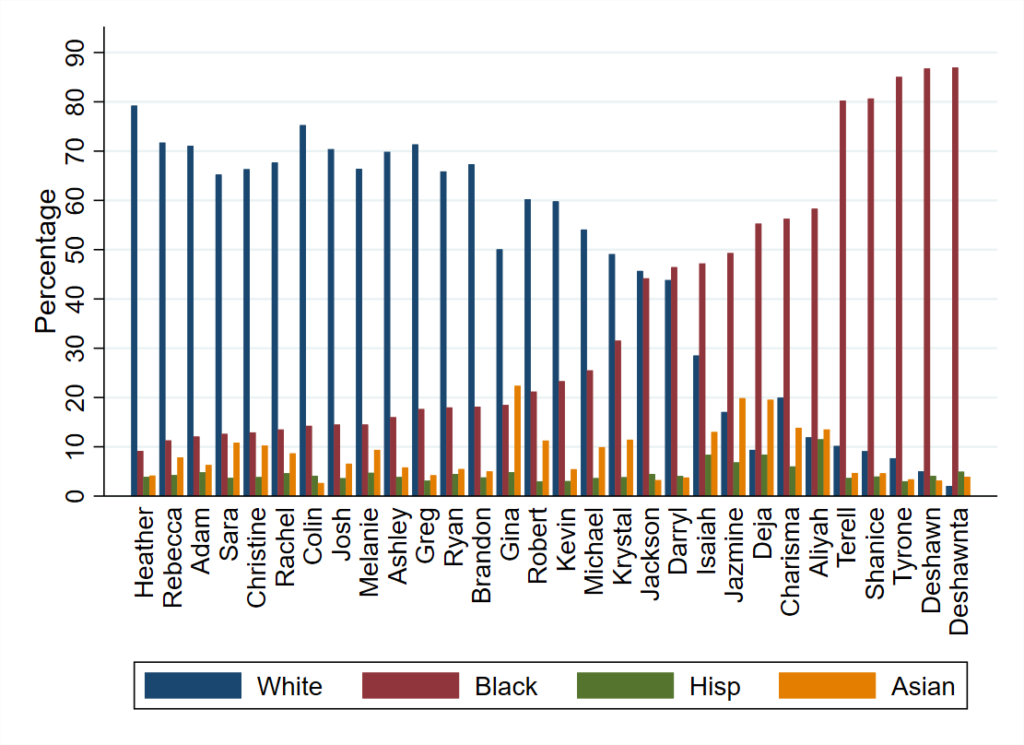

Figure 1 shows race associations for 30 first names from a nationally representative sample comprising 1,500 participants from all 50 U.S. states. To accurately elicit beliefs about race, the researchers asked people how many out of 10 people belong to different groups and offered monetary incentives for correct responses. It turned out that when people perceive a name as Black, they also expect this worker to have lower levels of education, productivity, and non-cognitive skills. For example, perceiving a name to be Black (compared to white) is associated with a 47% decrease in the predicted likelihood of holding a master’s degree and a 46% decrease in perceived trustworthiness. Most of this racial bias persists when only looking at the effect of variation in race association between employers for the same name.

What’s in a name? Less than people think!

In a next step the authors compared the perceived racial gap with actual data obtained from 2,400 workers who performed the same task. The perceived gap in productivity of 25.2% is nearly three times larger than the actual gap of 9%. This finding aligns with recent studies that demonstrate people’s tendency to form beliefs about minorities that exaggerate between-race differences.

Name associations contribute to hiring discrimination.

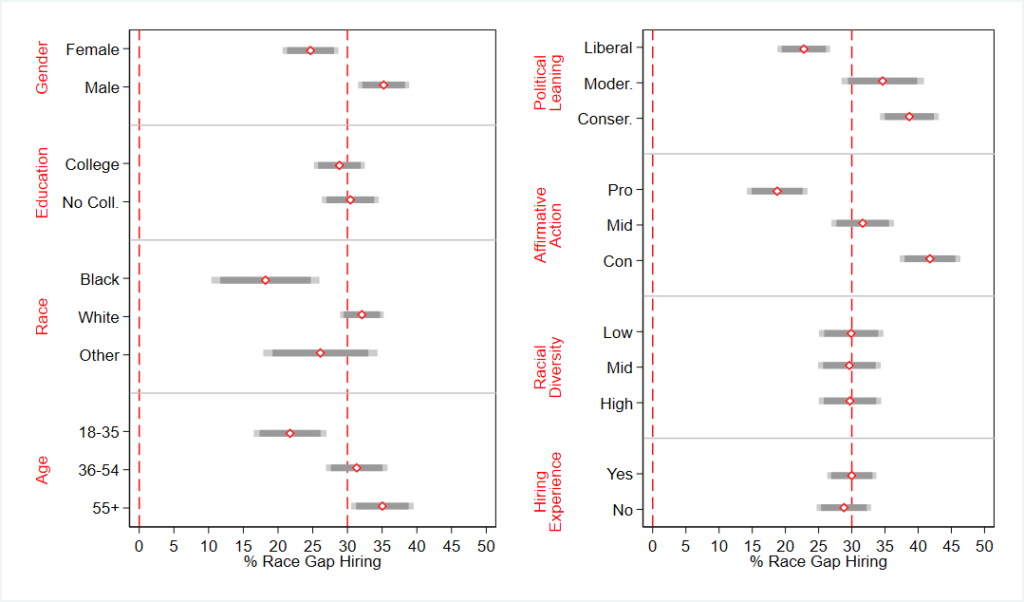

Participants were then presented with pairs of workers and tasked with making hiring decisions. Each time they chose the more productive worker, they received a small payment. The results indicate that workers whose names are perceived as Black face a 30 percentage points hiring disadvantage. Notably, Figure 2 illustrates substantial variation in discrimination across different employer groups, with higher levels of discrimination observed among male, older, white, and conservative employers. In contrast, the study found no correlation between discrimination and employers’ educational attainment, the level of racial diversity in their zip code, or their prior experience with hiring.

Employers use race as a decision heuristic

Hiring managers allocate very limited time to review each application, raising concerns that they may resort to heuristics or mental shortcuts based on race. Indeed, the researchers observe that greater differences in race perceptions among candidates lead to shorter decision times and increase confidence in their hiring decisions, even after accounting for variations in perceived productivity. Requiring employers to make decisions within a 2-second timeframe, which prompts instinctive decision-making, increases the racial gap in hiring by an additional 25%. Estimates from a neuro-psychological model of decision-making (DDM) show that under time pressure, people lower the information threshold and base their decision more on race perceptions, which are salient and thus easier to retrieve.

Who is most affected by time pressure?

Support for race-based affirmative action (AA) is the single biggest predictor of hiring discrimination (see Figure 2, top right). It also affects the responses to time pressure. Among white participants who oppose AA, the substantial hiring race gap of over 40% remains unaffected by time pressure. In contrast, those in favor of AA reduce discrimination from 34% to below 20% when provided with sufficient time. Results show this group overrides their instinctive, race-based assessments of workers and replaces them with more relevant productivity beliefs.

Name associations can hinder learning from new information and own memory

How much names affect people’s long-term economic outcomes remains an open question. Recent research suggests that names become less influential once people have access to more information about a person. However, other studies also indicate that (racial) biases can prevent people from collecting new information about others, leading them to refrain from interviewing a candidate, renting to certain individuals, or extending credits. The new study finds that biased beliefs can also impede individuals’ ability to learn from their own memory. Instead of seeking more nuanced information, many individuals overly rely on race associations when making decisions.