Across the globe, many businesses were forced to abruptly shift to having their employees Work From Home [WFH] during the Covid-19 pandemic. With a year of experience at WFH, there is now significant debate among businesses and policymakers about the extent to which WFH will continue once the pandemic is over. While some businesses (e.g., Facebook) have stated that they plan to continue offering full WFH for select employees, others have reported mixed results and plan to bring employees back to the office.

To date most studies of WFH have relied on survey data. However, such data might be problematic, due to inaccuracies in respondent answers. Moreover, especially during a crisis such as Covid, employees might overstate their productivity out of a concern about their career prospects. A new IZA discussion paper by Michael Gibbs, Friederike Mengel and Christoph Siemroth instead uses rich workplace analytics data to study the effects of the switch to WFH on employee productivity and work times. The data cover 10,000 information technology professionals in a large Asian IT services company. This setting is of particular interest because the industry and occupation have been predicted to be among the most amenable to WFH.

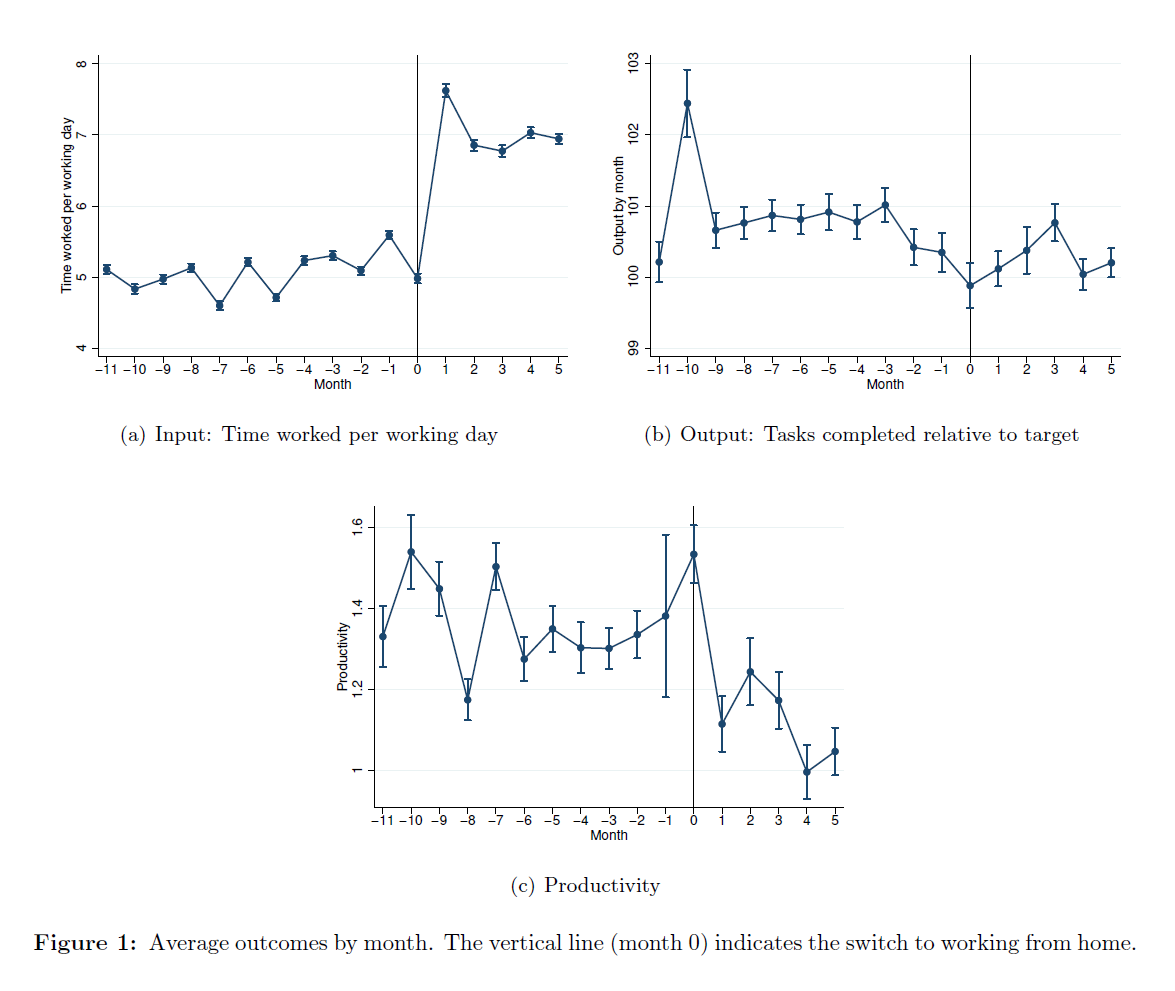

The authors used data from April 2019 through August 2020. This allowed them to compare productivity of the same employees before and during WFH, which began in March 2020. They were also able to study employee performance, hours worked, networking activity, and other collaboration patterns.

Longer working hours

During WFH, the study finds that employees maintained output and achieved goals at approximately the same levels as they did prior to the pandemic. However, in order to maintain this output, on average total work hours increased by about 30%, including an increase of 18% outside of normal business hours. Productivity – measured as output per work hour – declined by about 20%.

The increase in total work hours was not due to time saved by not having to commute. Based on an estimate of commute time for employees, the authors found no statistical association of commute times with changes in work hours and productivity during WFH. Hence, employees with longer commutes prior to WFH did not increase work hours more during WFH.

The researchers were also able to examine how WFH affected workers differently, depending on their characteristics. Employees with children at home experienced a larger drop in productivity, and increased total work hours by more than those without children to compensate. Women fared less well than men in WFH, based on working hours and productivity. However, this was not driven by the presence of children at home. The study also finds that employees with greater company experience performed better. This may indicate that they were able to be more effective during WFH, by drawing on their knowledge of company procedures, and their deeper network of colleagues.

More distractions at home

What explains the drop in productivity? The authors’ explanation is that there were more distractions at home – especially with children – and that the costs of communication and collaboration were significantly higher during WFH. Employees spent a great deal more time in formal meetings, including teleconferences. They also sent more emails than before. Meetings and other coordination activities appear to have been disruptive, as employees had significantly less “focus time” in which they were able to work without interruption. Additional evidence for this view is that employees networked less – they had fewer contacts with colleagues and business units both inside and outside the firm. Moreover, they had fewer meetings with their supervisor, or coaching sessions.

These findings are only for the first phase of WFH. Nevertheless, they provide a cautionary note that WFH is not a perfect substitute for personal interactions in the workplace. Companies will likely have to evolve practices which involve a mix of working from the office and home.