One of the most common explanations why women are underrepresented in many areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is that a hiring bias against women exists in those fields. A new study by Thomas Breda and Mélina Hillion, published as IZA DP No. 10079 and in Science, challenges this view. The authors show that in France the minority gender in a given field in academia is, on a very large scale, systematically favored during recruiting for high-level teaching positions in that field.

One of the most common explanations why women are underrepresented in many areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is that a hiring bias against women exists in those fields. A new study by Thomas Breda and Mélina Hillion, published as IZA DP No. 10079 and in Science, challenges this view. The authors show that in France the minority gender in a given field in academia is, on a very large scale, systematically favored during recruiting for high-level teaching positions in that field.

The analysis draws on rich administrative data on the three national exams used in France to recruit virtually all primary-school teachers (CRPE), middle- and high-school teachers (CAPES and Agrégation), as well as a large share of graduate school and university teachers (Agrégation).

Favored minority genders

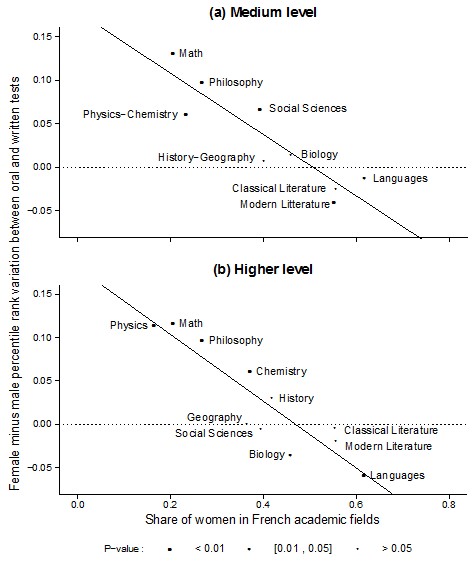

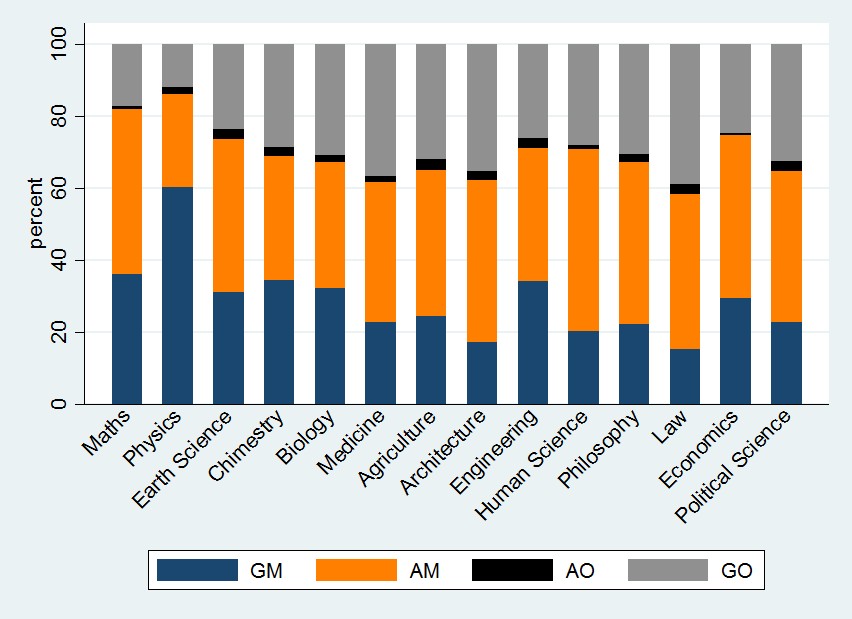

Using the specific design of these exams, the authors are able to compare the outcomes of two separate sections of the exam: an oral test in which the gender of the student is known and a written gender-blind test. The results of these exams, which cover about 100,000 individuals observed in 11 different fields (from Math and Physics to Modern Literature and Foreign Languages) over the period 2006-2013, reveal a bias in favor of women that is strongly increasing with the extent of a field’s male-domination (see figure below).

This bias turns from 3 to 5 percentile ranks for men in literature and foreign languages to about 10 percentile ranks for women in math, physics or philosophy.

y-axis: gap between females’ average percentile rank on non-blind oral tests and blind written tests, minus the same gap for men. It is computed for each field-specific exam at the high- and medium-level. The size of each point indicates the extent to which it is different from 0 (p-value from tests of Student).

x-axis: Fields’ extent of (non) male-domination measured by the share of women among academics in the fields (see (22) for alternative measures).

The authors point out, however, that the focus on STEM versus non STEM fields can be misleading to understand female underrepresentation in academia, as some STEM fields are not dominated by men (e.g., 54% of U.S. Ph.Ds. in molecular biology are women) while some non-STEM fields, including humanities, are male-dominated (e.g., only 31% of U.S. PhDs in philosophy are women).

Thus, by exploiting an oral test that is similar across all field-specific exams and using the fact that some candidates take several exams, Breda and Hillion are able to confirm that these findings reflect evaluation biases rather than a selection process of candidates across fields and/or gender differences in abilities between oral and written tests.

Preferences for women disappear in lower level positions

These results confirm evidence from a recent correspondence study that puts forward that women who have already specialized and heavily invested in their field can actually be favored in male-dominated fields when the recruiting is for positions at high levels (from secondary school teaching to professorial hiring).

In contrast, an analysis of the recruiting process for primary school teachers suggests that pro-women biases in male-dominated fields may disappear in less prestigious and less selective hiring exams, where candidates are not necessarily specialized. The bias in favor of women in male-dominated fields might even reverse at lower levels, as was found in two experiments done with medium-skilled applicants.

Discrimination may then still impair women’s chances to pursue a career in quantitative science (or philosophy), but only at early stages of the curriculum, before or just when they enter the pipeline that leads to a PhD or a professorial position.

Counteracting stereotypes should focus on early ages

In summary, Breda and Hillion suggest that there is no compelling evidence of hiring discrimination against individuals who have already decided against social norms to pursue an academic or a teaching career in a field where their own gender is in the minority.

The authors conclude that active policies aimed at counteracting stereotypes and discrimination should probably focus on early ages, before educational choices are made. By advertising that women have at least as good—or even better—opportunities as their male counterparts in higher positions could encourage more young women to study in those fields.

Finally, non-blind evaluation and hiring should be favored over blind-evaluation in order to reduce gender imbalances across academic fields. In particular, policies imposing anonymous CVs in the first stages of academic hiring are likely to reach opposite effects to those expected. This confirms the findings of a previous IZA study on the hiring process for fresh Ph.D. economists.

Minimum wages are a not just a hot policy issue in the United States and other highly developed nations. They are also a central aspect of the policy discourse in developing and transition economies, with diametrically opposite perspectives dominating the debate. Theory is ambiguous, and at its core this is an empirical question, not least because enforcement can vary across countries.

Minimum wages are a not just a hot policy issue in the United States and other highly developed nations. They are also a central aspect of the policy discourse in developing and transition economies, with diametrically opposite perspectives dominating the debate. Theory is ambiguous, and at its core this is an empirical question, not least because enforcement can vary across countries. To advance the understanding of the social influence of peers on consumption,

To advance the understanding of the social influence of peers on consumption,  Network effects also affect behavior in the labor market. In another recent paper, published as

Network effects also affect behavior in the labor market. In another recent paper, published as  A third new paper,

A third new paper,

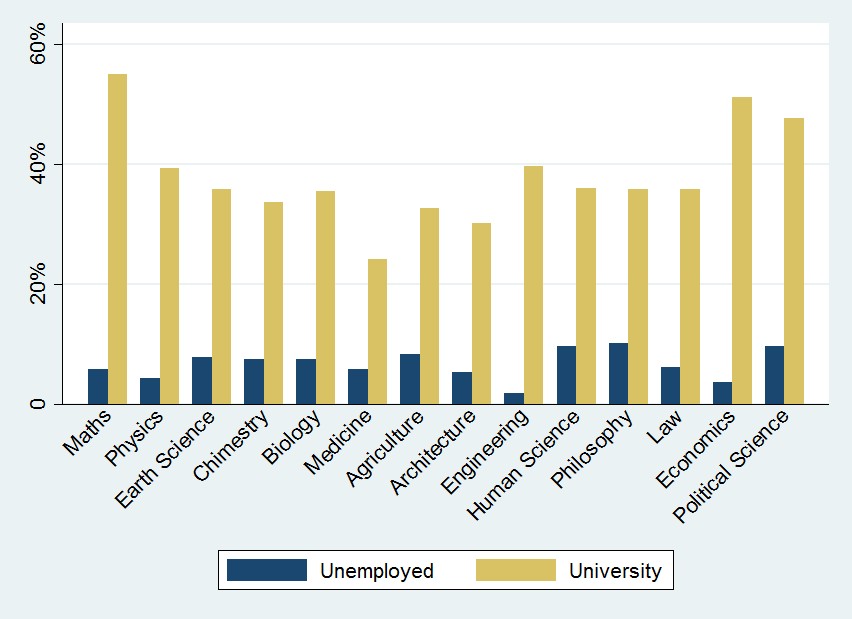

Gaining a Ph.D. possibly determines positive outcomes from both an individual and a societal perspective. For candidates, doctoral education is an investment aimed at acquiring skills and competences to be used in future career. For the society as a whole those who achieve a Ph.D. are likely promoters of innovation. In order to achieve these outcomes, Ph.D. holders must be able to get job positions that allow them to fully exploit their educational background. How frequently does this occur?

Gaining a Ph.D. possibly determines positive outcomes from both an individual and a societal perspective. For candidates, doctoral education is an investment aimed at acquiring skills and competences to be used in future career. For the society as a whole those who achieve a Ph.D. are likely promoters of innovation. In order to achieve these outcomes, Ph.D. holders must be able to get job positions that allow them to fully exploit their educational background. How frequently does this occur?

Over the last century, female labor participation has increased in almost all developed countries. The availability of child care and increased contraceptive access along with other institutional, cultural and policy changes have made it easier for women to reconcile family and career.

Over the last century, female labor participation has increased in almost all developed countries. The availability of child care and increased contraceptive access along with other institutional, cultural and policy changes have made it easier for women to reconcile family and career. Young adults who are still living with their parents and still in compulsory education finance their independent consumption using either parental transfers (pocket money), or by working part-time. Parents care about their own and their children’s consumption, but also about the effect that part-time work might have on their children’s study time and academic achievement, so are prepared to sacrifice some of their income to subsidize their children’s expenses.

Young adults who are still living with their parents and still in compulsory education finance their independent consumption using either parental transfers (pocket money), or by working part-time. Parents care about their own and their children’s consumption, but also about the effect that part-time work might have on their children’s study time and academic achievement, so are prepared to sacrifice some of their income to subsidize their children’s expenses.

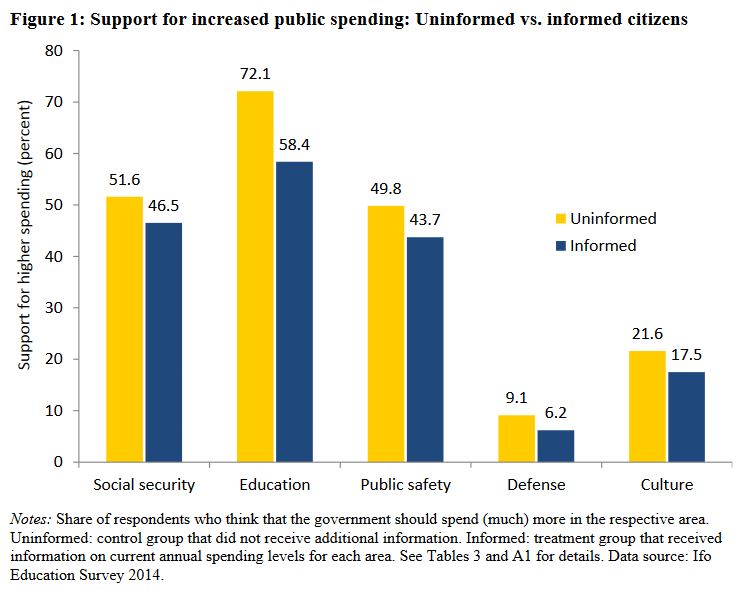

The results summarized in Figure 1 highlight a strong correlation between the provided (or withheld) spending information and the level of support for increased spending levels. Across all domains, the informed individuals showed less support for more spending compared to individuals who did not receive the information, with the strongest differences found for education.

The results summarized in Figure 1 highlight a strong correlation between the provided (or withheld) spending information and the level of support for increased spending levels. Across all domains, the informed individuals showed less support for more spending compared to individuals who did not receive the information, with the strongest differences found for education.

As an alternative to taxis, Uber entered the NYC market in May 2011 with surge pricing and mobile driver-passenger matching technology. Surge pricing means passengers pay a higher rate for the Uber service during times of high demand, which gives incentives to Uber drivers to provide rides in inclement conditions. Uber could thus be a logical response to unmet demand during poor weather.

As an alternative to taxis, Uber entered the NYC market in May 2011 with surge pricing and mobile driver-passenger matching technology. Surge pricing means passengers pay a higher rate for the Uber service during times of high demand, which gives incentives to Uber drivers to provide rides in inclement conditions. Uber could thus be a logical response to unmet demand during poor weather.