Since the 2008/09 global recession unemployment and inequality have been on a rise. Reforms of labor markets have been one prominent feature in different countries and regions over the last years, not least in the context of the 2008/09 global recession. There has also been a continued debate in both the academia and policy circles about the effects of labor market reforms and regulation.

There are some who argue that labor market reforms and regulation have adverse effects on employment growth, increase in temporary/part-time or informal forms of employment and that it leads to higher unemployment especially among youth. However, the empirical evidence has been quite mixed and the direction remains unclear. Along with labor market reforms, a wide range of active labor market policies were also introduced in both advanced and emerging economies to get the working age people off benefits and into during the crisis. Many of these policies or programs were defined and implemented differently across countries and the extent to which they were successful also differed.

Addressing inequality has been another objective for many countries since the economic crisis. There is a renewed interest since the 2008 economic crisis on minimum wages as a useful and relevant policy tool as more and more countries experience increase in both income and wage inequality. A number of emerging and developing economies have been more active in revising the minimum wages on a regular basis. Even in advanced countries, such as Germany, the UK, and the US, minimum wages have gained importance to address income inequality.

Finally, collective bargaining is a labor market institution that has long been recognized as a key instrument for addressing inequality in general and wage inequality in particular. A number of countries across the different regions also introduced non-contributory social security schemes to provide income to the poor and to reduce inequality.

To achieve a better understanding of the effects of labor market reforms and the effectiveness of public policies, a conference was hosted jointly by the ILO and IZA in March 2016 at the ILO headquarters in Geneva (see program). Co-organized by Werner Eichhorst on behalf of IZA, the conference provided the forum for a broad debate about the design and the effects of reforms affecting labor market institutions.

From the presentations it became clear that evidence on significant positive short-run effects of flexibility-enhancing reforms, e.g. with respect to employment protection on job creation is scarce. At the same time many speakers stressed the importance of a positive macro-economic environment to realize the full positive potential of labor market reforms instead of creating more instability in the labor market.

This is particularly true for reforms expanding unemployment benefits and active labor market policies while lowering employment protection. This flexicurity approach might be desirable as it reduces the risks of persistent unemployment and provides sufficient support for job seekers (see the most recent IZA paper by Eichhorst, Marx and Wehner) – however, job finding opportunities and funding requirements depend on economic dynamism.

Even though life expectancy is rising in most OECD countries, participation rates for older workers remain low. The fact that a non-negligible fraction of individuals exit the labor force well before retirement age has grave economic consequences, as it influences the economic dependency ratio of a country, that is, the ratio of retirees and unemployed over the employed.

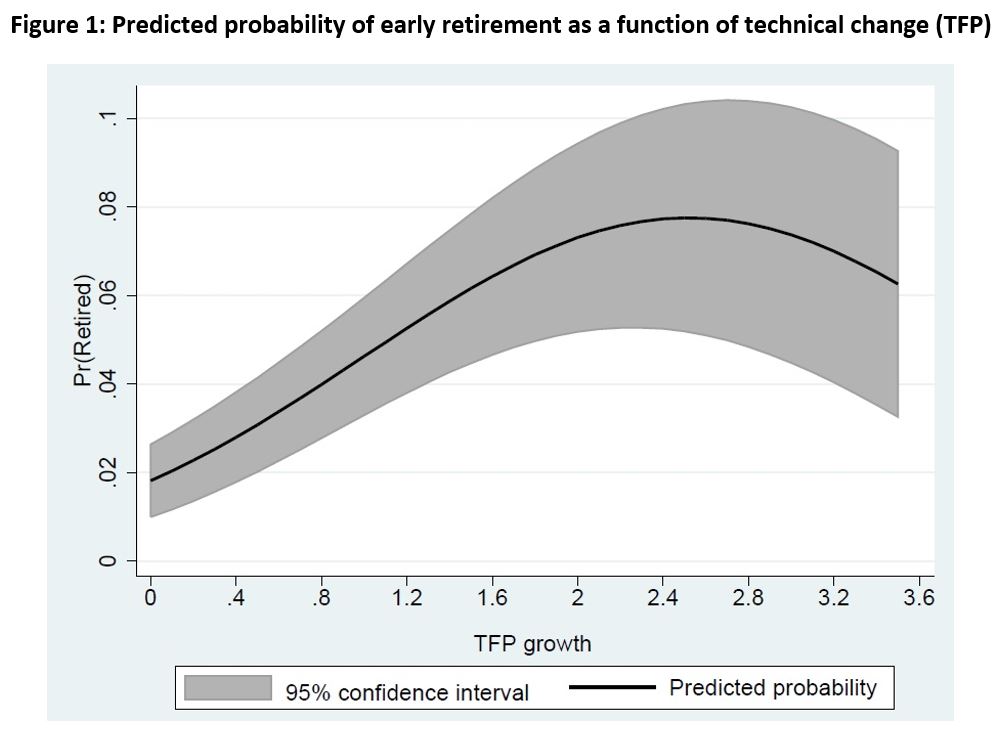

Even though life expectancy is rising in most OECD countries, participation rates for older workers remain low. The fact that a non-negligible fraction of individuals exit the labor force well before retirement age has grave economic consequences, as it influences the economic dependency ratio of a country, that is, the ratio of retirees and unemployed over the employed. The findings by Burlon and Vilalta-Bufí suggest that the higher the technical change, the more willing the elderly are to retrain, an insight which should be taken into account by policy makers. In the context of an aging society, the authors propose that policies should aim at delaying retirement and stimulate the participation of the elderly to the labor force.

The findings by Burlon and Vilalta-Bufí suggest that the higher the technical change, the more willing the elderly are to retrain, an insight which should be taken into account by policy makers. In the context of an aging society, the authors propose that policies should aim at delaying retirement and stimulate the participation of the elderly to the labor force. By

By

A new article published on

A new article published on  In order to curb unemployment, OECD countries have made enormous efforts and spent considerable sums on active labor market policies (0.6% of GDP in 2011). Governments have mainly relied on traditional measures such as job creation schemes, training programs, and wage subsidies which have often shown dissatisfactory impacts on income and employment prospects of participants.

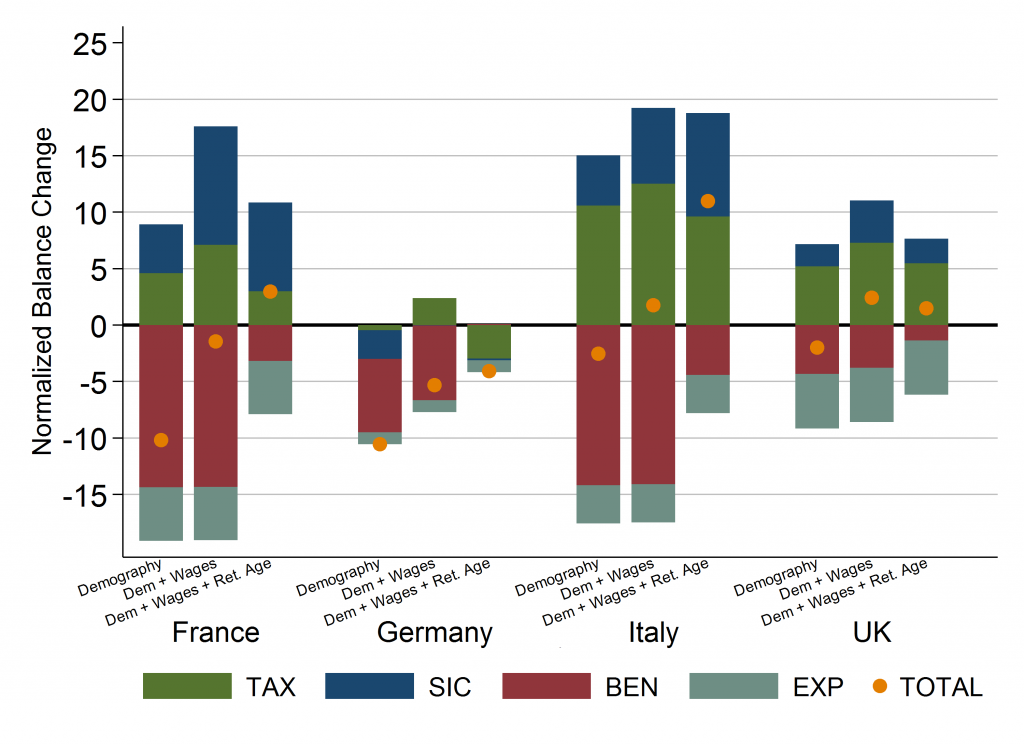

In order to curb unemployment, OECD countries have made enormous efforts and spent considerable sums on active labor market policies (0.6% of GDP in 2011). Governments have mainly relied on traditional measures such as job creation schemes, training programs, and wage subsidies which have often shown dissatisfactory impacts on income and employment prospects of participants. Demographic aging and accompanying shrinking labor forces are common phenomena throughout the developed world. There is a widespread notion that societal aging will put significant pressure on public budgets, a view supported by recent

Demographic aging and accompanying shrinking labor forces are common phenomena throughout the developed world. There is a widespread notion that societal aging will put significant pressure on public budgets, a view supported by recent

Today is

Today is

Recruitment is one of the most important decisions businesses face. To ensure productivity and profitability remains high it is crucial that the right people are in the right roles within the company. However, there is an important decision to make when recruiting new personnel: Should you recruit internally from existing company talent, or look for an injection of new ideas and skills from external candidates?

Recruitment is one of the most important decisions businesses face. To ensure productivity and profitability remains high it is crucial that the right people are in the right roles within the company. However, there is an important decision to make when recruiting new personnel: Should you recruit internally from existing company talent, or look for an injection of new ideas and skills from external candidates? Uber, Airbnb, TaskRabbit, and other online platforms have drastically reduced the price of micro-contracting and grown a “gig” economy, where workers must more frequently decide which potential employers to trust. Traditionally, workers have used labor unions and professional associations as a venue for exchanging information about working conditions and coordinating collective withdrawal of trade in order to discipline employers.

Uber, Airbnb, TaskRabbit, and other online platforms have drastically reduced the price of micro-contracting and grown a “gig” economy, where workers must more frequently decide which potential employers to trust. Traditionally, workers have used labor unions and professional associations as a venue for exchanging information about working conditions and coordinating collective withdrawal of trade in order to discipline employers.