A recent IZA World of Labor article suggests that gender differences in attitudes toward risk are less significant than previously claimed and cannot explain women’s under-representation in high-level occupations.

A recent IZA World of Labor article suggests that gender differences in attitudes toward risk are less significant than previously claimed and cannot explain women’s under-representation in high-level occupations.

The commonly accepted argument in the economics literature is that women are more risk averse than men. They are therefore less likely to choose a career path leading to high-level jobs in which a large share of the remuneration comes from bonuses based on company performance—deemed higher risk—and are, as a result, likely to be underrepresented in such positions.

As attitude toward risk is still generally considered an innate behavioral trait, attributing gender differences in labor market outcomes to gender differences in risk attitudes implies that policy interventions can play only a very restricted role in dealing with labor market inequality.

Female risk aversion overrated

Summarizing the recent experimental economics literature, Antonio Filippin (University of Milan & IZA) challenges the previous consensus about gender differences in risk attitudes. He argues that beliefs about higher risk aversion among women are stronger than the actual evidence supporting them. In fact, there is no direct proof demonstrating that greater female risk aversion can explain why women are underrepresented in top-level positions in the labor market.

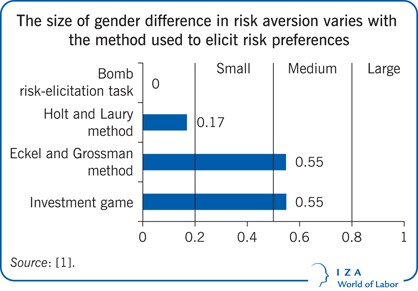

Moreover, recent research shows that gender differences in risk attitudes are neither large nor ubiquitous. Rather, gender explains only a very small fraction of the variance in risk attitudes, and even finding such differences depends on the method used to elicit the risk preferences.

Women ask, but they don’t get

Apart from their disadvantages in career advancement, women typically earn less than men. It is often argued that this may be because (i) women ‘don’t ask’ and (ii) the reason they fail to ask is out of concern for the quality of their relationships at work. This account is difficult to assess with standard labor-economics data sets. Hence a new IZA paper by Benjamin Artz, Amanda H. Goodall and Andrew J. Oswald examines direct survey evidence from Australia.

Using matched employer-employee data from 2013-14, the paper finds that the women-don’t-ask account is incorrect. Once an hours-of-work variable is included in ‘asking’ equations, hypotheses (i) and (ii) can be rejected. “If we find that women are asking and aren’t getting the pay rises, it points the finger toward discrimination,” says Amanda Goodall.

- Read the complete paper: Do Women Ask? (IZA DP No. 10183)

- View the coverage in the New York Times and on BBC.

Gender differences in behavior under competitive pressure

While the above studies find male-female differences in competitive behavior to be overrated, evidence from professional sports suggests that substantial gender differences do exist in high-pressure situations. Data on top male basketball (NBA playoffs) and top female basketball players (WNBA playoffs) reveal that men increase risk-taking when they could win the match with a risky strategy. Women, in contrast, reduce their risk-taking in these situations. The less time left in a match, the larger is this gap.

- Read the paper (IZA DP No. 10011):

Gender Differences in Risk-Taking: Evidence from Professional Basketball

However, such gender differences seem to disappear when women compete against men. In an analysis of 4,279 episodes of the popular US game show Jeopardy!, this surprising result emerges with remarkable consistency for the probability to (i) respond, (ii) respond correctly, and (iii) respond correctly in high-stakes situations. Even risk preferences in wagering decisions, where gender differences are especially pronounced, do not differ across gender once a woman competes against males. Derived from a large real-life setting, these findings suggest that gender differences in performance and risk attitudes are not gender-inherent, but rather emerge in distinct social environments.

- Read the paper (IZA DP No. 9669):

Gender in Jeopardy!: The Role of Opponent Gender in High-Stakes Competition

A third scenario – female competitors exposed to the presence of men without the element of direct competition – is analyzed in a new study that looks at data from the New York City Marathon. Being overtaken by men changes nothing about the anticipated rewards to female performance or the returns to effort in this competitive environment. However, lower-ability female runners are shown to reduce their pace after the initial passing by the fastest running men.

- Read the paper (IZA DP No. 10184):

Do Men Matter to Female Competition Even When They Don’t?

Further reading:

IZA World of Labor research on the gender gap and women in the labor market.