Teacher quality is key for student achievement. Individuals exposed to better teachers perform better in school, and are more likely to attend college and earn higher salaries. However, the payment schemes in most educational systems are based on lifetime job tenure and flat salaries that are usually linked to teachers’ seniority, providing little incentives for excellence in teaching.

Academics and policymakers have proposed tying teachers’ pay to their students’ performance in an attempt to increase teacher motivation, effort, and ultimately student learning. While pay-for-performance programs in education have been implemented in several developing countries such as India, Kenya, China, Chile, Brazil, Mexico, and more recently in Peru, evidence on their effectiveness is scant and inconclusive. In a recent IZA discussion paper, Cristina Bellés-Obrero and María Lombardi address this question in the context of Bono Escuela (BE), a nationwide teacher pay-for-performance program implemented in 2015 in all public secondary schools in Peru.

About Bono Escuela

BE is a collective teacher incentive in which all public secondary schools compete within a group of comparable schools on the basis of their annual performance. There are 409 groups in total, and the average BE group has 36 schools. Every teacher and the principal in schools ranked in the top 20% within their group obtain a fixed payment amounting to over a month’s salary.

The incentives provided by the BE are collective (at the school level), as all teachers are rewarded if their school wins, although the main performance measure used to rank schools is their average score in a 2015 nationwide math and language standardized test, taken only by 8th graders. This feature of the program, which the authors exploit in their identification, implies that a school’s probability of obtaining the bonus hinges on the achievement of 8th grade students in 2015.

Identifying the causal effect

The study relies on a novel administrative database which covers the universe of Peruvian students in 2013-2015. This database contains annual information on the grades awarded to students by their teachers in every subject (their “internal grades”), the main outcome variable in the study. Internal grades have the advantage of capturing the skills of students which are targeted by the program (i.e., their basic competencies in math and language) without directly influencing teachers’ likelihood of obtaining the bonus, thus making them less prone to manipulation. Importantly, teachers’ grading tactics should not be influenced by the incentive, since internal grades have no direct impact on a school’s BE score.

The availability of achievement measures for students in all grades allows to compare the changes in internal grades of 8th graders to those of 9th grade students attending the same school, before and after the incentive was introduced, providing difference-in-difference estimates of the effect of BE on student achievement. Using data on the overlap of teachers in 8th and 9th grade, the authors assess whether the BE had an impact on student achievement in their comparison group, and discard the existence of any spillovers which could bias the estimates.

No impact on student achievement

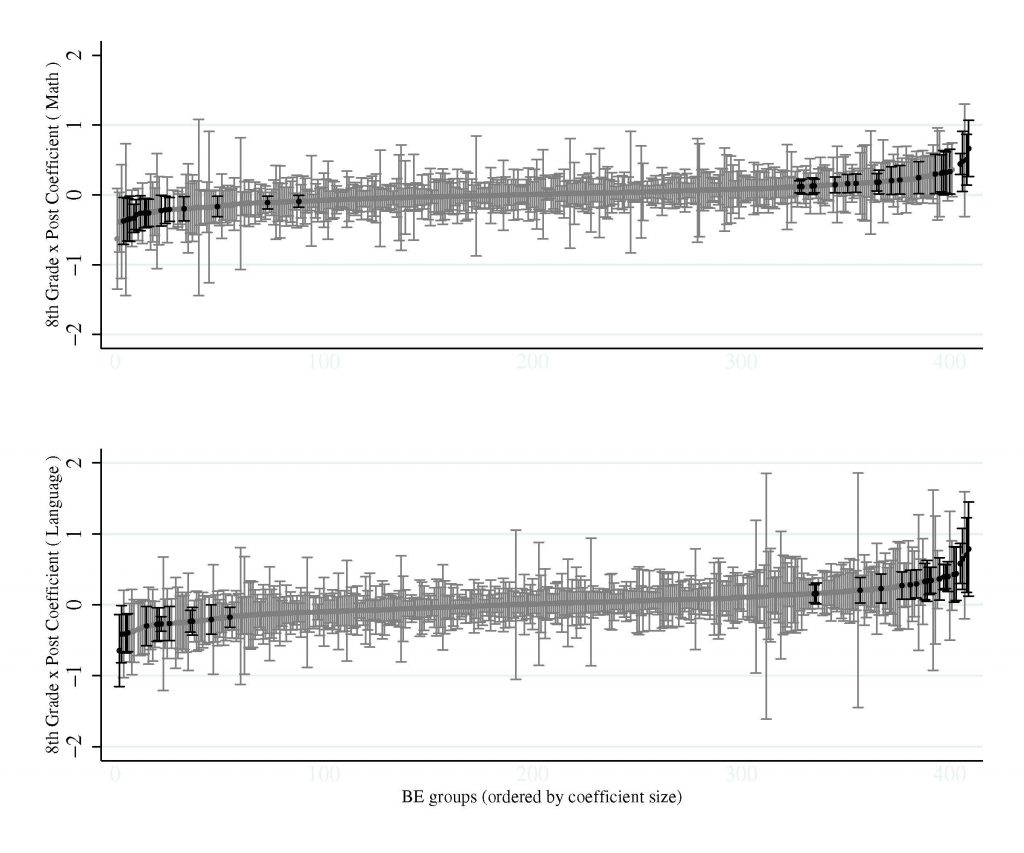

Despite the fact that the incentive was large, BE had no impact on students’ math and language internal grades. The coefficients are precisely estimated, allowing the authors to reject effects larger than 0.010 standard deviations (SD) in math, and 0.017 SD in language, well below the treatment effects found in previous studies on monetary incentives for teachers in India and Chile. When separately examining the impact of the program in each of the 409 BE tournaments (Figure below), the study finds little variance around the zero average effects, providing additional evidence of the null effect of BE on student achievement.

Why didn’t student learning increase?

The study provides suggestive evidence that the null effect is not a result of the size or collective nature of the incentive, or driven by teachers being uninformed about the BE, or only focusing on increasing standardized test scores – the incentivized outcome – without influencing their students’ learning in a meaningful way. The authors argue that certain features of the standardized test linked to the bonus might have hampered teachers’ ability to boost student performance in terms of this measure, potentially discouraging them from exerting higher effort.

Since the standardized test tied to the bonus was implemented for the first time in secondary schools in 2015, teachers might not have known what pedagogical practices result in higher test scores. Given that they had no prior experience with the standardized test tied to BE, this is not unlikely. The fact that students had no stakes in these evaluations might also have played a role in weakening the mapping between teachers’ effort and their chances of winning the bonus, as suggested by the findings of a teacher performance pay program in Mexican high schools.

Policy implications

Most of the existing studies on teacher pay-for-performance tackle this topic using relatively small interventions led by NGOs. While these experimental studies provide proof-of-concept of whether performance pay is an adequate tool for increasing student achievement, their findings are not necessarily generalizable to a scaled-up program. Budgetary constraints and opposition from teacher unions make several features of these types of interventions unfeasible in a nationwide program. It is thus crucial to better understand the role played by the features of teacher pay-for-performance programs in their success.