Immigration from Muslim countries is a source of tensions in many Western countries. Several countries have adopted regulations restricting religious expression and emphasizing the neutrality of the public sphere. A recent IZA discussion paper by Eric Maurin and Nicolas Navarrete explores the effect of one of the most emblematic of these regulations: the prohibition of Islamic veils in French schools.

In September 1994, a circular from the French Ministry of Education asked teachers and principals to ban Islamic veils in public schools. In March 2004, the parliament took one step further and enshrined prohibition in law.

The paper provides evidence that these new regulations contributed to improving the educational outcomes of female students with a Muslim background and to reducing educational inequalities between Muslim and non-Muslim students.

High school graduation rates improve for Muslim girls

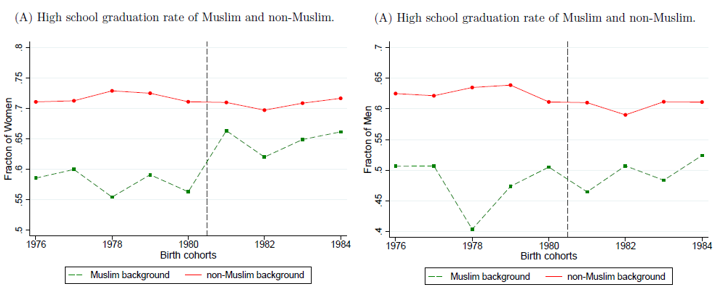

In particular, comparing women with and without a Muslim background shows a marked increase in the proportion of high school graduates in the Muslim group for cohorts born in 1981 and after, namely for cohorts who reached puberty (and the age of wearing the veil) just after the 1994 circular.

A comparison of men with different religious backgrounds shows no similar increase in the proportion of high school graduates in the Muslim group for cohorts born in 1981 and after, consistent with the assumption that the increase observed for women is driven by a policy targeting female students.

The figure below illustrates these trends in high school graduation rates for girls (left panel) and boys (right panel) with and without a Muslim background.

French secularism (laïcité) is often accused of going too far in upholding the principle of the neutrality of the state and the public sphere (including public schools), to the detriment of the exercise of freedom of religion. The findings of the study call for a more nuanced view, suggesting that the very implementation of more restrictive policies in public schools ended up promoting the educational empowerment of some of the most disadvantaged groups of female students.

Nonetheless, the authors point out that the stricter 2004 law did not generate any additional improvements. They also stress that such policies may not have the same effect in other countries.