Will robots and artificial intelligence take our jobs? This question has been at the center of an intense public debate on the future of work. In this debate it is often overlooked that the task content of a given job may vary substantially, both within occupations and across countries.

In many countries the share of routine jobs – both cognitive and manual – has declined over time, presumably because such jobs are easily replaced by computers or automation, or can be outsourced to other countries.

Much of the existing research assumes that occupations are more or less the same across countries. But considering the large differences in labor productivity, technology adoption and skills between countries, this assumption appears questionable.

In a new IZA discussion paper, Piotr Lewandowski, Albert Park, Wojciech Hardy, and Yang Du present evidence that occupations are actually quite different in international comparison: Workers in countries with higher technology use, higher skills and broader participation in global value chains tend to perform less routine-intensive tasks.

To quantify the country-specific job tasks, the authors use micro-data collected from large-scale surveys of workers (PIAAC, STEP, and CULS) in 42 countries around the world spanning developed and developing countries.

They develop harmonized measures of occupational task content across occupations and countries. These measures describe the share of routine and non-routine tasks that are performed by workers of a specific job in a specific country to capture differences in job tasks across countries.

More non-routine tasks in developed economies

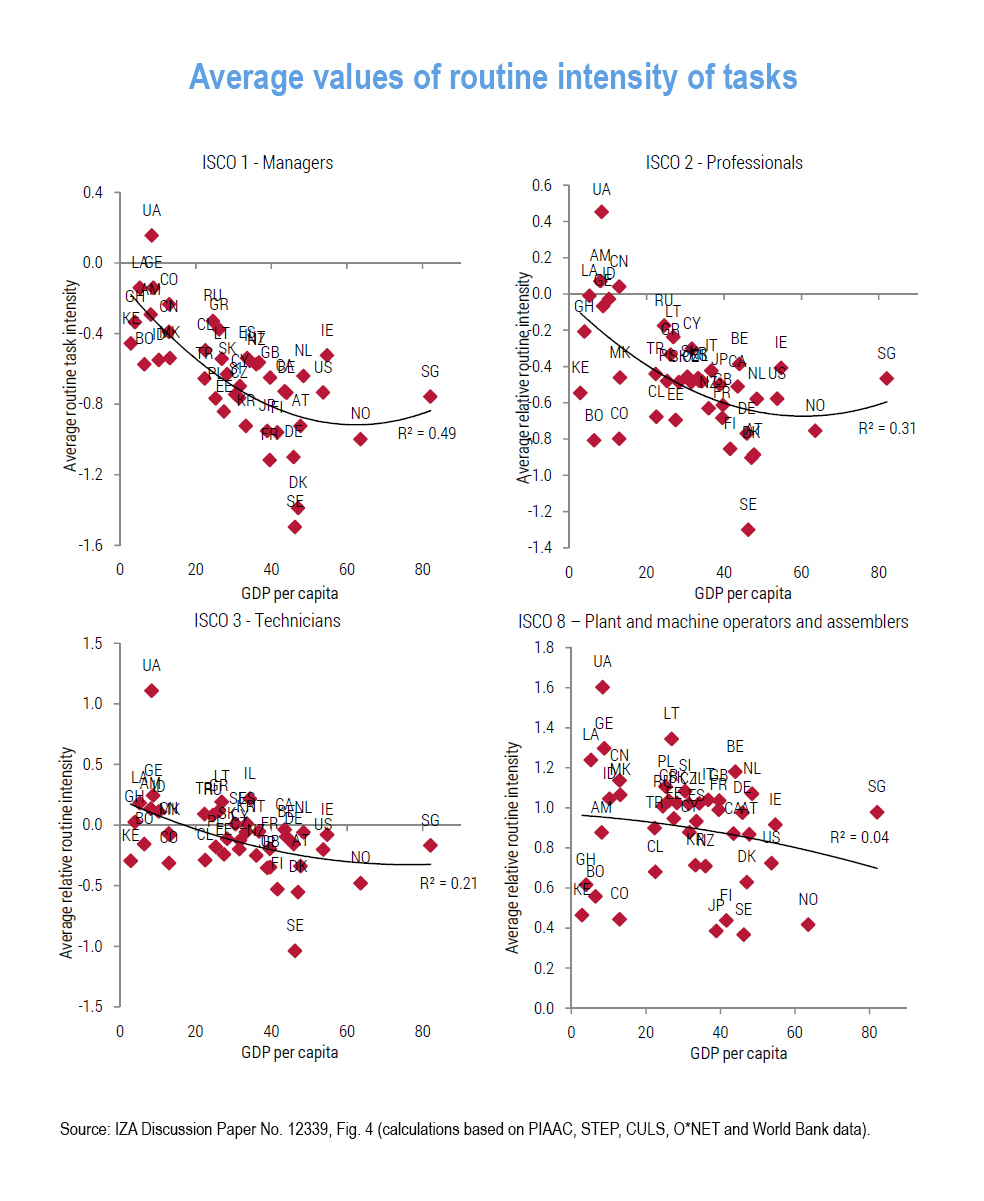

These differences turn out to be substantial, even within the same occupations. On average, workers in the more developed economies – especially in the high-skilled occupations– perform more non-routine cognitive tasks, both analytical and interpersonal, and fewer routine tasks.

In other words, the routine intensity of tasks performed by managers, professionals and technicians in developing countries is much higher than the routine intensity of tasks performed by their counterparts in the US, Germany or Scandinavian countries.

Therefore, studies that assume identical occupations around the world and apply the US-based measures to countries at noticeably lower stage of development will overestimate the importance of non-routine tasks in poor countries. They may also spuriously attribute wage premia enjoyed by these workers to technological change.

Therefore, studies that assume identical occupations around the world and apply the US-based measures to countries at noticeably lower stage of development will overestimate the importance of non-routine tasks in poor countries. They may also spuriously attribute wage premia enjoyed by these workers to technological change.

At the same time, for middle-skill occupations like clerical workers, and low-skill occupations like plant and machine operators and assemblers, the relative routine intensity of tasks varies considerably across countries but is not systematically related to the country’s level of development.

The role of technology, globalization and skills

The authors attribute the cross-country differences in tasks to three fundamental forces – technology, globalization, and supply of skills. International differences in the use of computers and other technology can best explain the cross-country variation in routine intensity in high-skilled occupations. This highlights the complementarity between non-routine tasks and ICT.

Globalization, in particular specialization of countries in narrow sections of global value chains, contributes the most to cross-country differences in routine intensity among workers in low-skilled and offshorable occupations. This confirms the view that offshoring enables countries to specialize, within industries, according to their abundant factors, so that poorer countries specialize in routine tasks and richer countries specialize in non-routine tasks.

Finally, the supply of skills also plays a role, especially in the low- and middle income countries, where lower supply of skills accounts for a large share of the difference in routine intensity compared to the most advanced countries.

The supply of skills is often overlooked in the studies of tasks that are focused on the most developed countries. However, this new evidence shows that it in the poorer countries it should be accounted for as it may help to understand not only why the shares of high-skilled occupations are low, but also why the tasks performed by workers in given occupations are more routine-intensive.

In sum, the paper stresses that cross-country differences in task content of jobs are sizable. Understanding the extent and nature of these differences is of both scientific and policy relevance, as they reflect differences in the nature of work that can inform future labor market challenges, such as the share of jobs that can be automated.