The past four decades have seen a drastic increase in radiation exposure. Today, the average individual receives almost twice the annual dose of radiation compared with 1980. This increase is almost entirely due to man-made sources of radiation such as CT scans, x-rays or mammograms, as well as flying, during which people are exposed to cosmic radiation.

However, while there is no doubt about the negative consequences of very high doses of radiation — those received by survivors of an atomic bomb or a nuclear disaster — the literature has reached no consensus on the consequences of small (subclinical) doses of radiation.

A recent discussion paper by IZA researchers Benjamin Elsner and Florian Wozny analyzes to what extent low doses of radiation, prevalent on a day-to-day basis in a developed country, affect cognitive skill development. To provide an estimate of the causal effect of radiation, they use a natural experiment: the regional variation in nuclear fallout caused by the Chernobyl disaster in 1986. After a failed simulation of a power cut, an uncontrolled chain reaction led to the explosion of a nuclear power reactor, with a radioactive cloud drifting over Europe in the week after the accident.

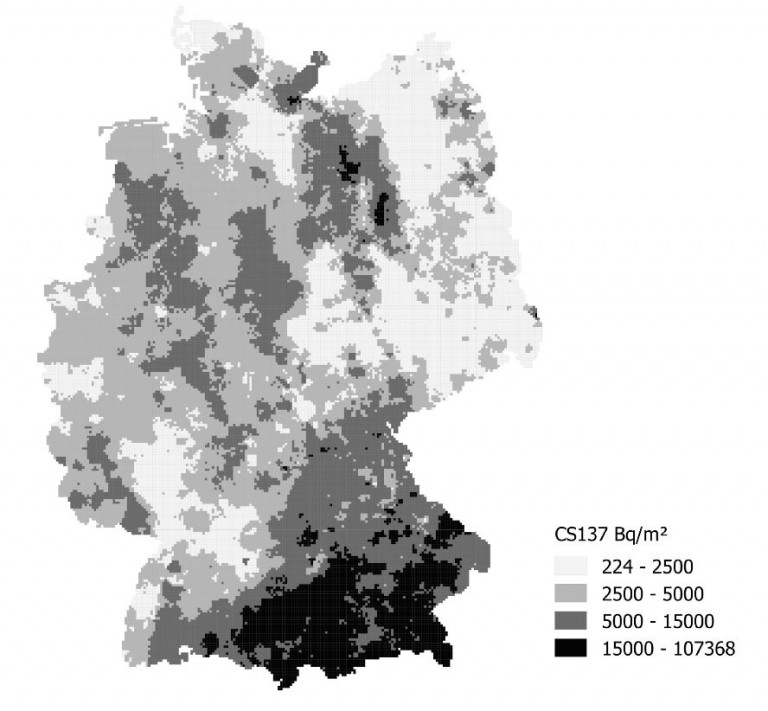

German regions were exposed to this cloud of radioactive fallout dependent on the rainfall during the critical period when the contaminated cloud was hanging over Germany. The highest level of fallout went to Bavaria and Baden-Wuerttemberg in the south, as well as parts of former East Germany. Differences in contamination are considerable, with the most affected soils displaying a contamination 500 times as strong as in the least affected region. Today, more than half of the fallout is still in the ground, although over time it has been washed out into deeper layers of soil, thereby reducing the external exposure of the population. However, exposure through ingestion is possible until today, as certain foods — in particular mushrooms and game — still exceed radiation limits in parts of southern Germany.

One Bq defines the activity of radioactive material in which one nucleus decays per second.

Using survey data on cognitive tests as well as a residential history with data for the Chernobyl-induced soil surface contamination provided by the Federal Office for Radiation Protection, the authors show that especially older cohorts who lived in highly-contaminated areas perform significantly worse in cognitive tests 25 years after the accident. These results not only underscore the potential negative consequences of nuclear power generation. They also suggest that even low doses of radiation, e.g. caused by medical procedures and air travel, have human capital costs. Policymakers can help minimize these costs by reducing the number of unnecessary CT scans and investing in alternative sources of energy.

The study by Elsner and Wozny received the Best Paper Award at the Spring Meeting of Young Economists in Palma de Mallorca, the Second Prize at the Health and Environment Conference in Essen, and the Novartis Prize for the best health paper at the Annual Conference of the Irish Economic Association in Dublin.