Economic theory provides ambiguous predictions about the effect of wage increases on the allocation of time between leisure and work. On the one hand, a wage increase makes the individual richer, lowering the preferred hours of work. On the other hand, higher wages raise the opportunity cost of not working (the money one could have earned instead of spending time for leisure), pushing up the preferred number of working hours.

Economic theory provides ambiguous predictions about the effect of wage increases on the allocation of time between leisure and work. On the one hand, a wage increase makes the individual richer, lowering the preferred hours of work. On the other hand, higher wages raise the opportunity cost of not working (the money one could have earned instead of spending time for leisure), pushing up the preferred number of working hours.

Empirically, it is tricky to evaluate how and to what extent changes in the wage affect labor force participation. One of the main problems is that wage increases do not appear out of thin air, but are paid for being more productive. That makes it difficult to distinguish between the effects of higher wages and higher productivity.

In a recent IZA discussion paper, Matteo Picchio (Marche Polytechnic University), Sigrid Suetens (Tilburg University) and Jan van Ours (Tilburg University) use a very special kind of windfall money to disentangle the effect of higher income on labor supply: the unique case of lottery winners.

Lottery data are matched to administrative data on jobs

Lottery prizes have the advantage that, in contrast to wage increases, they are unexpected and unrelated to productivity changes of the winners. Since the size of the lottery prizes is determined by a random draw, they are as close as one can get to an unforeseen, potentially substantial, increase in permanent income.

For the purpose of the study, lottery data from lottery players who were subscribed to participate in the Dutch State Lottery between 2005 and 2008 was matched by Statistics Netherlands to two administrative datasets: the Municipal Personal Records Database, containing demographic, family, and residence information and the Social Statistical Database of Jobs, containing information on salaried jobs. Merging these different datasets allowed the researchers to track lottery winners over a number of years and study their labor supply responses in terms of employment and earnings.

Winning money affects time spent working, but not probability of working

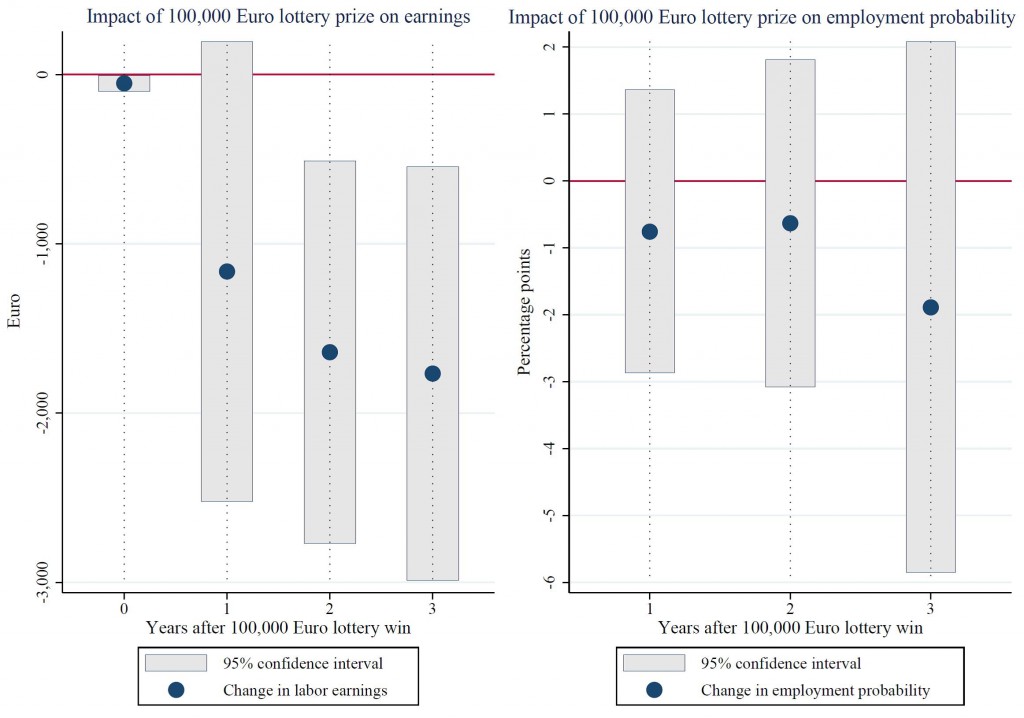

The figure below displays the effects of a €100,000 lottery prize on labor earnings and employment probabilities. If an employee wins €100,000, earnings go down by an amount of €50 in the same year. In later years, the effect is larger, possibly because it takes some time for employees to organize their ‘new’ working hours. In the first year after winning a lottery prize of €100,000, earnings go down by an amount of €1,160. Two years later this is €1,640 and after three years it is €1,770. The effect thus seems to persist over time.

The authors do not find significant effects of lottery prizes on the probability of being employed per se. The results suggest that winning a large prize induces workers to work fewer hours but does not lead them to withdraw completely from the labor market. In the last part of the study, the authors show that these results are driven by young, single individuals without children.