Parents, teachers and policymakers alike are concerned with adolescents engaging in risky practices, such as drug abuse, unprotected sex, or all kinds of delinquent behaviors (stealing, fighting, etc.). Adolescents are often motivated by short-term benefits while potentially not foreseeing associated detrimental effects on educational achievement, health and career outcomes. Peer pressure has long been discussed in the social sciences literature as one of the main drivers behind teenage risky behaviors, though knowledge behind specific mechanisms relating peer characteristics to individual behavior remains incomplete.

Parents, teachers and policymakers alike are concerned with adolescents engaging in risky practices, such as drug abuse, unprotected sex, or all kinds of delinquent behaviors (stealing, fighting, etc.). Adolescents are often motivated by short-term benefits while potentially not foreseeing associated detrimental effects on educational achievement, health and career outcomes. Peer pressure has long been discussed in the social sciences literature as one of the main drivers behind teenage risky behaviors, though knowledge behind specific mechanisms relating peer characteristics to individual behavior remains incomplete.

In their new discussion paper, IZA researchers Benjamin Elsner and Ingo E. Isphording explore a specific channel through which peers affects risky behaviors: a student’s ordinal rank in a school cohort.

Consider two similar students with the same ability and similar socioeconomic background. By chance, both end up in two different grades, where the first is surrounded by very well performing peers, so that he ranks among the less able students in his grade. The second student is surrounded by less able peers, so that this student is ranked among the best students in his grade. Elsner and Isphording pose the question: to what extent does this difference in the ordinal rank affect the behavior of these otherwise similar students?

There are at least two theoretical reasons why the ordinal rank may influence risky behaviors. First, a student surrounded by high-achieving peers (i.e. who has a low relative ability) might erroneously infer lower likelihoods of a successful career which would lower the expected costs of a bad health status, earlier pregnancies or incarcerations. Second, low-ranked students might think of risky behaviors as a way to gain reputation among their peers, instead of gaining status through academic achievement.

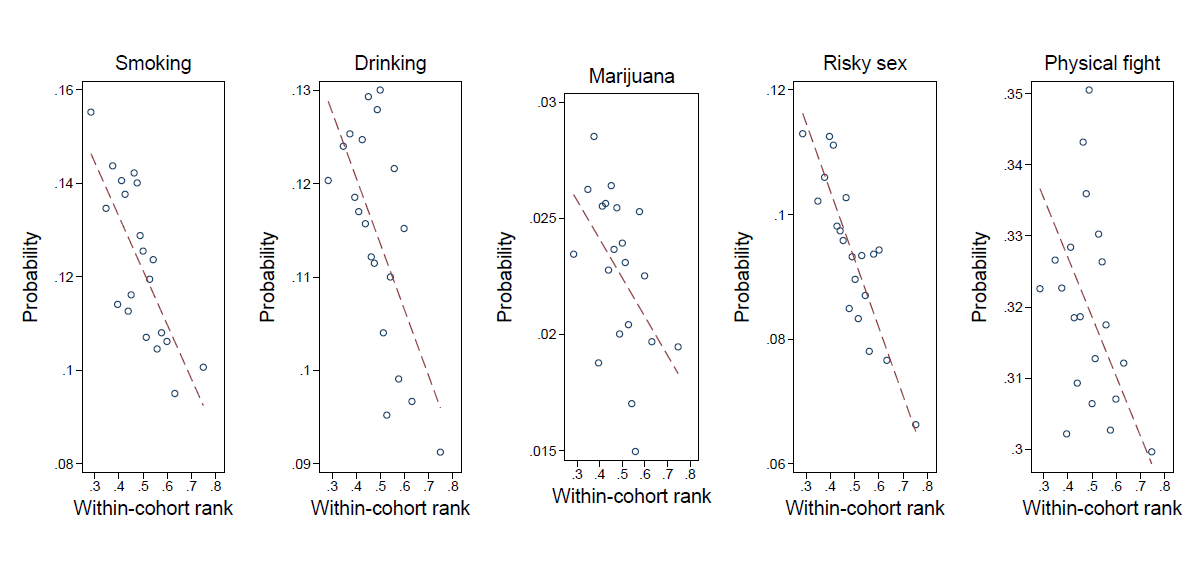

Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth), a representative panel survey of US middle and high school students, the authors compare students who end up in different ranks because they started school in different school years. Using this within schools/across grades research design, the authors can exclude many potential confounding factors like strategic school choice and quality differences across schools. A first graphical summary of their results hints at a strong negative association between the ordinal rank and different kinds of risky behavior.

A thorough statistical analysis that takes into account differences in background characteristics as well as potential effects of drug abuse on cognitive ability reveals strong negative effects of the ordinal rank on smoking, alcohol abuse, and the probabilities of engaging in unprotected sex and physical fights, arguably behaviors that are associated with severe long-term costs.

These results should be of concern for parents and policymakers: Choosing the best possible school is not always optimal, because a child with a low rank in the best school may be more inclined to engage in risky behavior than she would be in the second-best school. Moreover, given that risky behaviors impose a significant cost for society, it is important to know their determinants in order to design interventions that prevent adolescents from engaging in them, e.g. through specifically targeting low-ranked students and informing them about the long-run consequences of risky behaviors.