Following the considerable growth in women’s representation among economics students and faculty during the 1970s and 1980s, progress has leveled off in the last two decades. A new IZA discussion paper by Shelly Lundberg and Jenna Stearns documents trends in the gender composition of academic economists over the past 25 years, the extent to which these trends encompass the most elite departments, and how women’s representation across fields of study within economics has changed.

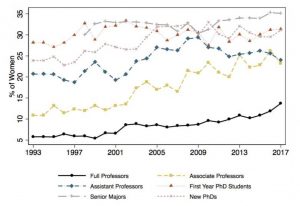

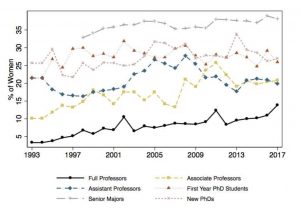

Substantial progress was made during the 1970s and 1980s in the representation of female faculty within the 43 economics departments at U.S. universities known as the Chairman’s Group – a set of highly-ranked departments for which the faculty and graduate student gender composition can be tracked over a 45-year period. In 1972, women accounted for only 2 percent of full professors, 4 percent of associate professors, and 9 percent of assistant professors. In 1993, the fraction of full professors who were female had tripled to 6 percent, 11 percent of associate professors were women, and the female share of assistant professors had more than doubled to 21 percent.

Declining female share at the junior faculty level

However, between 1993 and 2017, the proportion of senior female faculty grew at a much slower pace. Among full professors, the female share increased from 6 percent to more than 13 percent, and among associate professors, from 11 to 23 percent. For assistant professors, the share of women increased from 20 percent in 1993 to 29 percent in 2009, but dropped again to 24 percent in 2017.

In the departments rated in the top 20 by US News and World Report, the representation of women among full professors was only 3 percent in 1993, grew slowly to 10 percent in recent years, and then rose to nearly 14 percent in 2017. The female fraction of associate professors, increased from 10 percent to as high as 26 percent in 2011, but has declined in recent years to about 20 percent. Female representation among assistant professors stood at about 21 percent in 1993, reached a peak of 27.6 percent in 2008, and has since fallen back to 20 percent, meaning that no net progress has been made at the junior faculty level in top 20 departments over the past 24 years.

More progress in other disciplines

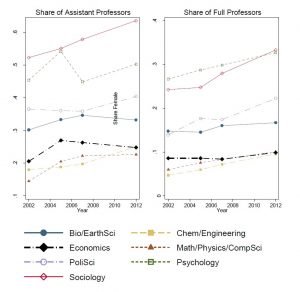

Evidently, economics has made less headway than the science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields in terms of increasing the share of female undergraduate majors and PhD recipients, which will make it even more difficult to close the faculty gender gap in economics going forward. Furthermore, common explanations for female academic disadvantage, such as heavier domestic responsibilities and an aversion to math intensity, fail to explain why economics is falling behind these other fields in terms of female persistence and promotion probabilities. What can explain the unique challenges that women seem to face in economics?

Toxic environment in male-dominated fields

An adversarial and aggressive culture within academic economics is often advanced as a causal force in women’s stalled progress in the profession, though its impact is difficult to quantify. Economics seminars, for example, have a reputation for being particularly hostile environments. The culture of an academic discipline can have gendered implications if women either fail to fully adapt to the culture or if they receive differential treatment as a result of it.

Female economists appear to be less likely to engage in practices that are positively correlated with professional success, suggesting an inability or unwillingness to adapt to professional norms. For example, male academics self-cite more than female academics in many fields, but the male-to-female self-cite ratio is twice as high and more persistent in economics. Applied economics fields attract a higher proportion of women, but this work is still seen by some as less rigorous or less important than traditionally male-dominated topics. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women may choose to go into less male-dominated fields or leave academia altogether based on early experiences with toxic environments that men are more likely to tolerate.

Harassment and disrespect

It is obviously difficult to obtain quantitative estimates of the extent of outright harassment of women in economics. There are many reports of women in economics experiencing inappropriate behavior in job interviews, seminars, meetings, and at conferences. In addition, the language used to describe female economists on at least one anonymous online forum is often sexual and derogatory, in a way that it is not for men.

Recent evidence suggests that gender harassment is a problem in academics more broadly. Such behavior is often normalized and tolerated in male-dominated settings, making it difficult to change. Thus, the National Academies of Sciences offer several evidence based recommendations to address harassment in the university setting that may be directly relevant to economics. In particular, they advise reducing the importance of hierarchical relationships and implementing “power-diffusion” mechanisms such as mentoring networks. They also argue that taking explicit actions to achieve greater gender equity in the hiring and promotion process is an essential step in creating a diverse and respectful environment.

Disparate assessment of men and women

The evidence summarized by Lundberg and Stearns suggests two primary mechanisms through which the barriers against women in economics may operate: differences in productivity between men and women, and differences in how they are evaluated. Women may be on average less productive than men due to childbearing and other family responsibilities, a higher propensity to engage in service activities instead of research, or differences in the type of research in which they choose to invest their time. The distinct experiences of men and women in the profession may also contribute to productivity gaps that arise as a result of differences in collaborative networks, access to mentors, and gender harassment.

But gender gaps conditional on productivity are also larger in economics than in other academic disciplines, suggesting that a second factor explaining female disadvantage in economics may be disparate assessment of men and women. Equal-ability women appear to be held to higher standards than men, and need to publish more, higher quality work to achieve equal levels of success in this profession.

Gender gap in beliefs on equal opportunity

The study concludes that continued progress toward equality in academic economics will require a widespread awareness that these barriers exist, accompanied by a concerted effort to remove opportunities for bias in the hiring and promotion process. However, first steps have been slow in coming. A 2008 survey of AEA members found, in addition to substantial differences in the policy views of male and female economists, a meaningful gender gap in their beliefs on equal opportunity in the profession. While 76 percent of female AEA members believed that opportunities for economics faculty in the US favor men, fewer than 20 percent of men shared the same view. In fact, one-third of male economists felt that opportunities in economics actually favor women. To the extent that such beliefs persist, they are a major obstacle to the development of new diversity initiatives.

According to the authors, diversifying the economics profession is important, because a greater breadth of individual perspectives will affect what is taught in the classroom, what research questions are asked, and how policy discussions are addressed. In addition, to the extent that women’s stalled progress in economics is the result of discrimination or biased assessment, as recent evidence suggests, continued action to remove these barriers can be justified both on the basis of simple fairness and also on the benefits of creating an environment where equal work yields equal rewards.