Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

Human development starts early, and neuroscientists point to the first three years of brain development as especially consequential. Foundations for academic and social success later in life are created through the experiences in children’s earliest years.

Parents, relatives and many other non-relatives are responsible for the upbringing of children in modern societies. Public policy plays a crucial role in the process, either through the regulation of market-based care or through the direct provision of subsidized child care services. It is critical to understand the constraints and the incentives faced by families to choose a certain combination of caregivers for their young children.

There is little evidence available on how public policies that expand access to early care services during the first 36 months of life affect household behavior and consequently dictate effects on child development. A recent IZA discussion paper by Juan Chaparro and Aaron Sojourner, from the University of Minnesota, explores this issue using data from the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP).

Same program, different outcomes

The IHDP was an intervention done in the United States during the 1980s with the goal of supporting the development of low birth weight and premature babies. Participants were selected at birth and randomly assigned to either a treatment or control group. Infants in the treatment group had access to home visits and free, high-quality childcare service between the ages of 12 months and 36 months. Family income was not a selection criteria for participation.

Therefore, the IHDP allows the study of household behavior across a broad range of family economic circumstances. 608 infants were assigned to the control group and 377 to the treatment group. The IHDP also collected extraordinarily rich data on quality and quantity of maternal and non-maternal care each child experienced, the allocation of mothers’ time between child care, work, and other uses, and each child’s skill development.

Previous literature has found a positive and significant treatment effect of the IHDP intervention on cognitive development by the end of the program, especially among children with birth weight closer to normal (Gross et al., 1997) and among children from low-income families (Duncan & Sojourner, 2013). However, each of these dimensions represents an opaque combination of stable characteristics and family choices. For instance, family income reflects parents’ choice of how many hours to work in the labor market and how much they can earn per hour. Low-income families include those who work for low wages and those with higher-earning potential who do not work outside the home.

Chaparro and Sojourner offer new evidence on the mechanisms driving the differences in effects. Their study explores if there are differences in the treatment effects depending on three key dimensions of heterogeneity across families: 1) the mother’s potential wage in the labor market; 2) the quality of prenatal investments chosen by the mother; and 3) the child’s endowment at birth, a measure of differences in child health status at birth compared to other children born under similar circumstances.

Interaction between quantity and quality of care matters

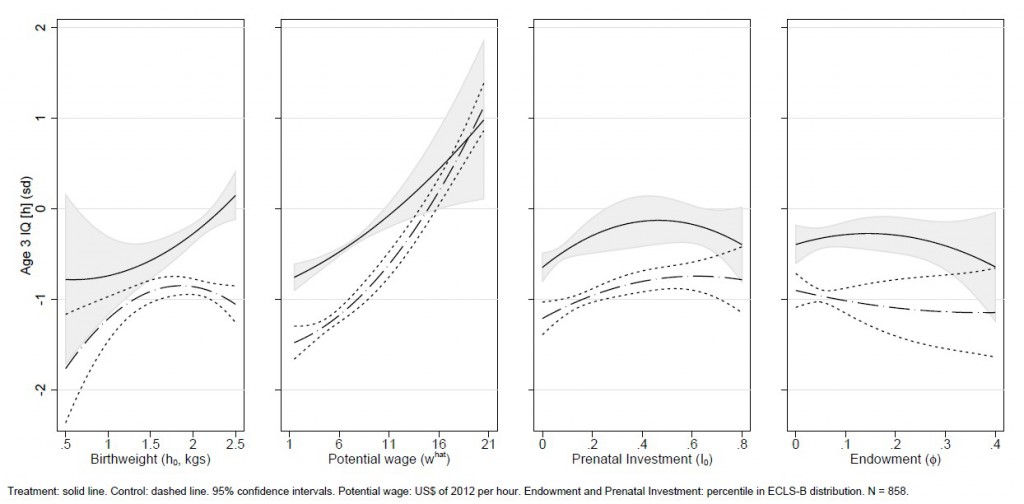

Figure 1 presents the gap of IQ at 36 months between children in the treatment and control group. The program had an effect on infants with a birth weight of at least 1.5 kilograms (first panel). The treatment effect varies by the mother’s potential wage (second panel). Children of mothers who could earn only a very low wage are the ones who benefited the most. The program had almost no effect on the cognitive development of children from mothers with a high earning potential in the labor market.

(National average = 100; Standard deviation = 16)

Any effect of the IHDP intervention on child development must account for how families react to the intervention by reallocating their time and money, thus providing the child with a new combination of care inputs. The paper by Chaparro and Sojourner finds evidence of time and effort reallocation in response to the IHDP intervention across different types of families.

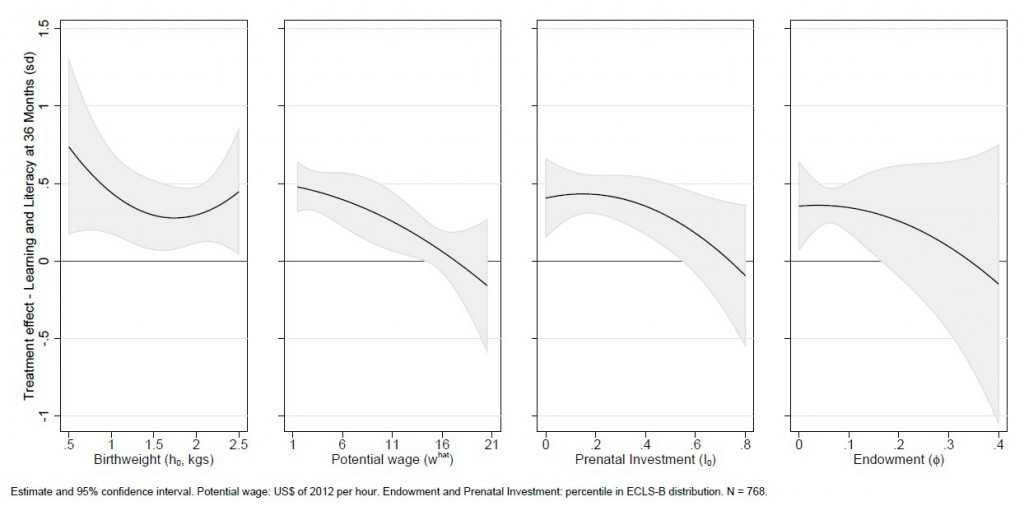

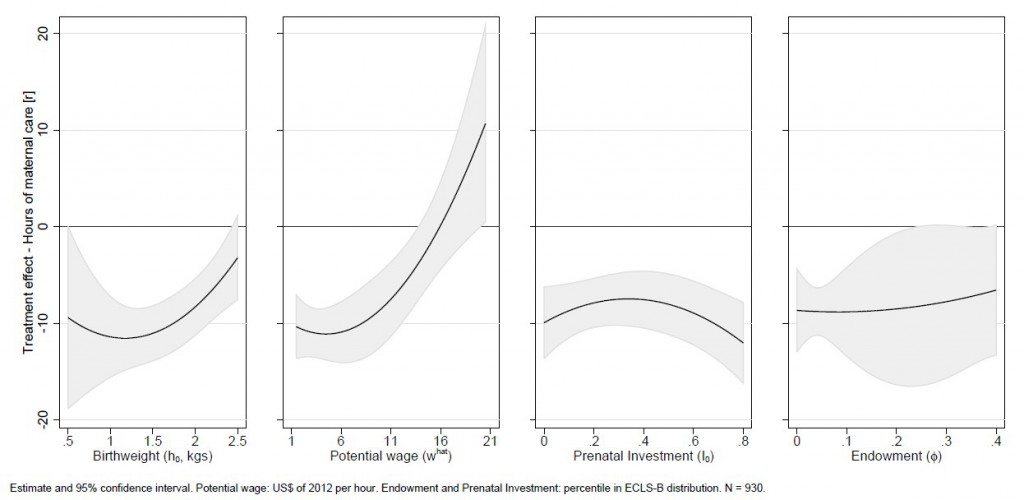

Consider Figures 2 and 3. They summarize the treatment effect on the quality and quantity of maternal care. The quality of maternal care is measured using components of the HOME score related to the promotion of learning and literacy, and the quantity of maternal care is measured in hours per week. The IHDP intervention triggered substantial changes in the behavior of low-wage mothers. The quality of maternal care provided by mothers with a low earnings potential was positively affected by the intervention (Figure 2, second panel). Simultaneously, this same group of mothers reduced their hours per week of maternal care (Figure 3, second panel).

In contrast to mother’s potential wage, neither differences in prenatal investment levels, which may proxy for family willingness to invest in child human capital development, nor differences in child endowment explain much of the variation in effects on child development or household resource allocation.

In conclusion, the paper offers new evidence that subsidies for high-quality early care improve child development especially among children in families with tight budget constraints due to low earning power. Biological factors and individual preferences appear much less important in driving the differences. Policies that promote the access to early childcare services must take into account the quality of the services provided and how different types of households will reallocate their own resources in response. Potential positive effects of any intervention could be augmented or eliminated by how families react to them.